The Sincere Graphomaniac from Vilnius

Wincenty Ignacy Marewicz was a prolific, yet clearly undervalued and even ridiculed writer. His life, that he himself so honestly depicted, resembled a string of failures. As a poor nobleman, he constantly sought support of the powerful, longed for a “little plot of land,” dreamed of a family and even created a project of family life, but the women he loved rejected him.

Half a century after the writer’s death, Eustachy Tyszkiewicz found a number of Marewicz’s works in the library of his family and wrote a study on him. Tyszkiewicz portrayed Marewicz as a failure, who wrote too much and too honestly about himself. Such fame followed the writer for many years and he was largely forgotten in Vilnius, the city where he spent a considerable part of his life.

Pursuit of happiness and a lover named Barbara, turned Laura

Wincenty Ignacy Marewicz was born in 1755 near Trakai. He studied in the Vilnius Jesuit School, but dropped out because the teachers, he later noted, were too strict. In search of happiness, he began a seven-year journey around the country in 1776 and, after spending all his money, returned to Vilnius in 1783.

“

Although Wincenty Ignacy never met her again, Barbara (or Laura) became the object of his poetry for many years to come.

There he took some geometry classes and proposed, yet in vain, to Barbara, a noble girl, whom he later called Laura in his works. She and her aunt lived in the Bernardine convent near St Michael’s Church. It was there that Marewicz first saw her and immediately fell in love. He would visit Barbara in her home and bring poems dedicated to her. Eventually he decided that a larger work would make a stronger impression, so he wrote a comedy “Love for Virtue” and staged it in 1783 with an amateur troupe. Marewicz invited Barbara to the premiere and, while acting on stage, did his best to let her know that the play was dedicated to her. The girl, nevertheless, rejected the suitor.

Although Wincenty Ignacy never met her again, Barbara (or Laura) became the object of his poetry for many years to come. According to Marewicz, it was his love for Barbara that made him a writer. “Without love, I would have been sturdier, calmer and happier, yet I would have remained surrounded by a haze of obscurity, sitting in a corner forgotten by all, while now they call me the Author.”

New inspirations in Warsaw and Vilnius

In 1786 Marewicz arrived in Warsaw, began writing a lot, and published his work en masse. He was about to marry a local woman (and later called her Rose in his works), but she rejected him. Saddened by yet another upset, he returned to Vilnius in late 1788 and continued his writer’s career.

Marewicz’s written legacy is remarkably plentiful and varied, ranging from political projects (“On Voluntary Taxes, a Project for Parliament”), poetry and letters in verses and prose, to treatises, satirical essays, erotic pieces, panegyrics, occasional patriotic poems, and moralising love comedies. Besides, he published a collection of sayings, part of them eavesdropped, the rest concocted himself.

Do You Know?

Desperate for funding and support, Marewicz complemented all his published writings with long, of up to twenty pages, dedications to the rich and the mighty. He also tried to sell his books by sending them out and even visiting private houses in person as a bookseller. Writer’s trade should have ensured him, he believed, considerable wealth, appropriate social status, and a happy family life. The impoverished author was convinced that the well-to-do had to take care of the lowly, the idea that gave him courage to seek help from the magnateswho did not know him.

The dedication to Aleksander Sapieha, the Chancellor of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, likens the writer to a tiny grass, while the magnate is described as a tall and mighty tree, casting down its tender shadow. Marewicz was a firm believer in the equality of the estates and professed that personal virtues, rather than riches and social status, should be the main criteria to value people.

Writer and protagonist in one

“

Marewicz was particularly critical of immoral and emancipated women who had, in his view, neglected their innate virtues, and even more damning of certain categories of men, including dandies, free-thinkers indifferent to their fatherland and mother tongue, as well as traitors, shams, promiscuous women and profligate priests.

Marewicz may well be seen as a sentimentalist taken to the extreme, for his authenticity usually resulted in showing himself as the most interesting object, while he held utmost sincerity and honesty to be undeniable virtues. He firmly believed that all the women had rejected him because he was poor and made no secret of that. Likewise, he had been rebuffed by the society because he bowed to no one. Hence, he truthfully depicted his hapless love affairs and failed engagement attempts.

In terms of writing quality, most Marewicz’s books are no worse than similar texts by many of his contemporaries. However, his peers were ready to sneer at the exceptionally candid author to the extent they did not even notice his irony, something he resorted to on so many occasions. For instance, the description of his mother’s library (consisting of mere thirteen books in reality) includes astonishing titles, all made up by Marewicz, such as “The Lyre of Heavenly Melody and the Off-tune Bugle, or the Loud Moaning of the Condemned to Hellish Suffering”.

For Marewicz, city was the place where all the vices of civilization thrived, while purity was only to be found in rustic life.

Marewicz was particularly critical of immoral and emancipated women who had, in his view, neglected their innate virtues, and even more damning of certain categories of men, including dandies, free-thinkers indifferent to their fatherland and mother tongue, as well as traitors, shams, promiscuous women and profligate priests. Among other things, he denounced the luxury of city life that included so many worthless details, such as tree shaping, fountains (the maintenance of which takes the money away from the needy families), theatre devoid of virtue, and air-polluting illuminations.

Veiled political declarations

“

Opera Polusia, córka kołodzieia czyli wolność oswobodzona (Polusia, the Daughter of a Wheel-maker, or the Liberated Freedom) is among his most popular works.

Opera Polusia, córka kołodzieia czyli wolność oswobodzona (Polusia, the Daughter of a Wheel-maker, or the Liberated Freedom) is among his most popular works. A political pamphlet against the politics of the Russian Empire in regard to the occupied Poland and Lithuania, enjoyed as many as seven editions in the span of three years and was staged in Vilnius in 1795. The main characters include Swobodzki (Freeman, the assumed monarch), who rules over the land called Wolność (Freedom); his supervisor Przemocka (Lady Violence, or Catherine II) and her room maid Polusia (Poland), whom Swobodzki is in love with.

Przemocka does all in her power to prevent Swobodzki from marrying Polusia. The nuptials, though, take place in spite of everything, and the newlyweds start planning their life: the management of their lands, the relation with their subjects and the revival of their cities. As these were extremely important topics at the time, no wonder the opera became so popular.

The house and the savings for the sake of the state

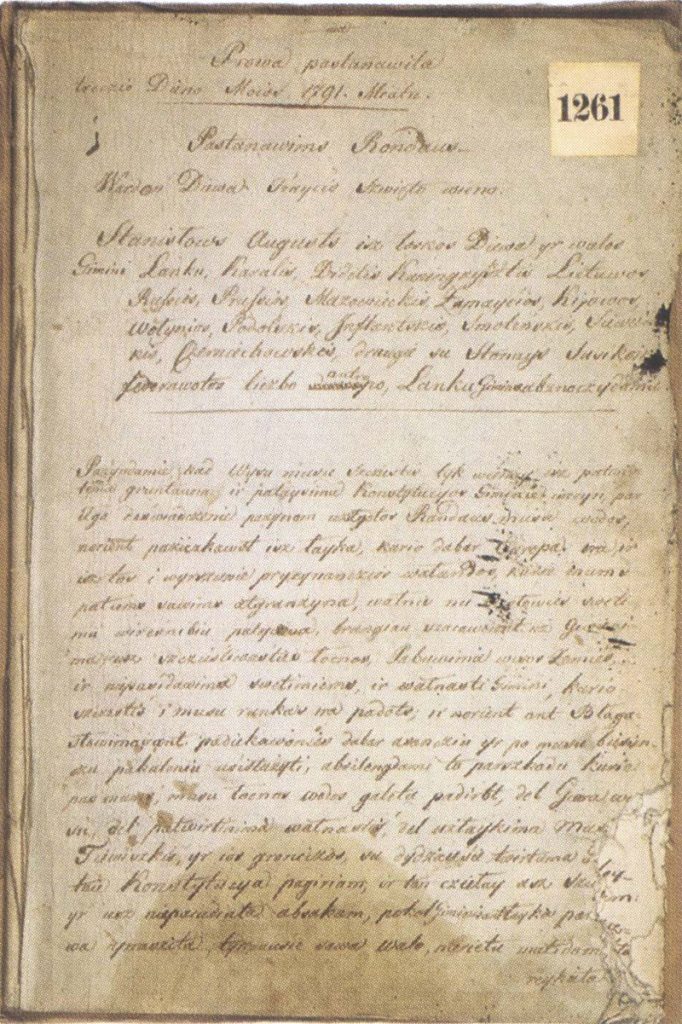

In early 1791 Marewicz’s work eventually bore tangible fruit. Castellan of Vilnius Maciej Radziwilłł, one of the nobles Marewicz dedicated his book to, awarded the writer with enough money to buy a house and a plot of land nearby the present-day Lukiškės Square.

On 3 May 1792, as the Commonwealth was celebrating the first year of the Constitution, Marewicz adorned his backyard in as sophisticated a manner as he could. He made a small hill and named it Mount Stanisław in honour of the King Stanisław August Poniatowski. The hill was topped with decorations symbolising the social structure and the equality of classes, stipulated by the Constitution.

“

Just several weeks later, as Russians were advancing on Vilnius, the writer donated his house and land for the needs of the army of the Commonwealth.

Just several weeks later, as Russians were advancing on Vilnius, the writer donated his house and land for the needs of the army of the Commonwealth. Moreover, he gave 269 złotys in cash and hundreds of books worth another 2,000 złotys for the defence of the city. He also bought equipment, which included a firearm, a horse and a hussar uniform, for a volunteer. Eventually, in 1794, he took part – together with his wife – in the national insurrection against Russian occupation led by Tadeusz Kosciuszko.

After the collapse of the Polish and Lithuanian Commonwealth Marewicz lived in Vilnius, writing occasional poems and dramas. Some of them had been staged with the playwright and his wife as actors. They lived in Lviv and Warsaw since late 1798 before returning in Vilnius in 1802 where Marewicz was involved in litigation regarding his house. He went to Warsaw again in 1806 and soon joined the Temple of Isis, the local Masonic lodge. Considered a graphomaniac by most major publishers, he had almost none of his works published at that time.

He died in Warsaw in 1822. In June of that year the Public Library bought a total of 140 volumes from Marewicz’s widow containing his oeuvre.

Lina Balaišytė