Attacks Against Jews During the Carnival in Vilnius

Archive books from the Vilnius Council retained a complaint filed by two Jewish Vilnans, Aaron Lewkowicz and Mojżesz Jakubowicz, on 13 February 1673. The document states “In the current year, one thousand six hundred seventy-three, the twelfth day of the month of February, the aforementioned Lord Italians, having undertaken evil council, harmful to poor people, having dressed themselves up in some sort of strange, never-before-seen garb, in turbans, Turkish style, with masks on their faces, contrary to the custom of this city, around ten people, and offering the occasion and incitement to the common people for tumults to the great and unbearable harm of the plaintiff s, driving back and forth several times on two sleighs on German Street, purposefully passing [the entrance to] Jewish Street, seeking a cause and an occasion for a tumult, they ordered their sleigh drivers to beat the Jews with their whips on their faces, their eyes, which they did indeed do.” (Frick, 2013,406)

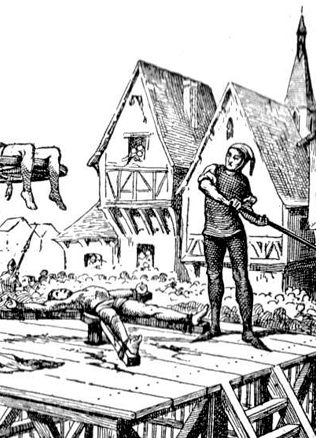

Italians on a rampage in the streets of Vilnius

The Italians mentioned in the complaint were Bartłomiej Tukan, Józef Bonfili, and Bartłomiej Cynaki, were citizens of Vilnius. Józef Bonfili was married to a local Lutheran, while Bartłomiej Cynaki was the royal secretary and a burgomaster of Vilnius. He would later become the Wójt (or the mayor in current terms) of the city.

The incident took place during a special time, the days of the carnival. That year the carnival began on 3 February, while the aforementioned February 12 was Sunday before the Ash Wednesday. As with most carnivals and celebrations of the time, excited people lost control. The masked Italians who attacked the Jews also took part in the carnival, no wonder the plaintiffs emphasized their unfamiliar garb.

The complaint provides a number of details:

Do You Know?

“Whenever they were able, they whipped and beat the Jews, threw down their hats, and pushed the many assembled people into other streets. The stronger ones, while passing by Žydų Street and making great noise, […] shouted there, ‘Beat, beat those Jews’, and then the drivers whipped the faces of those within their reach[…], and then all of them attacked the Jews and hit them with clubs, rocks and bricks; many were injured and maimed and many lost their hats and clothing that the offenders stuffed into a barrel on their sledge. The open windows were smashed and destroyed and the school battered badly with rocks.”

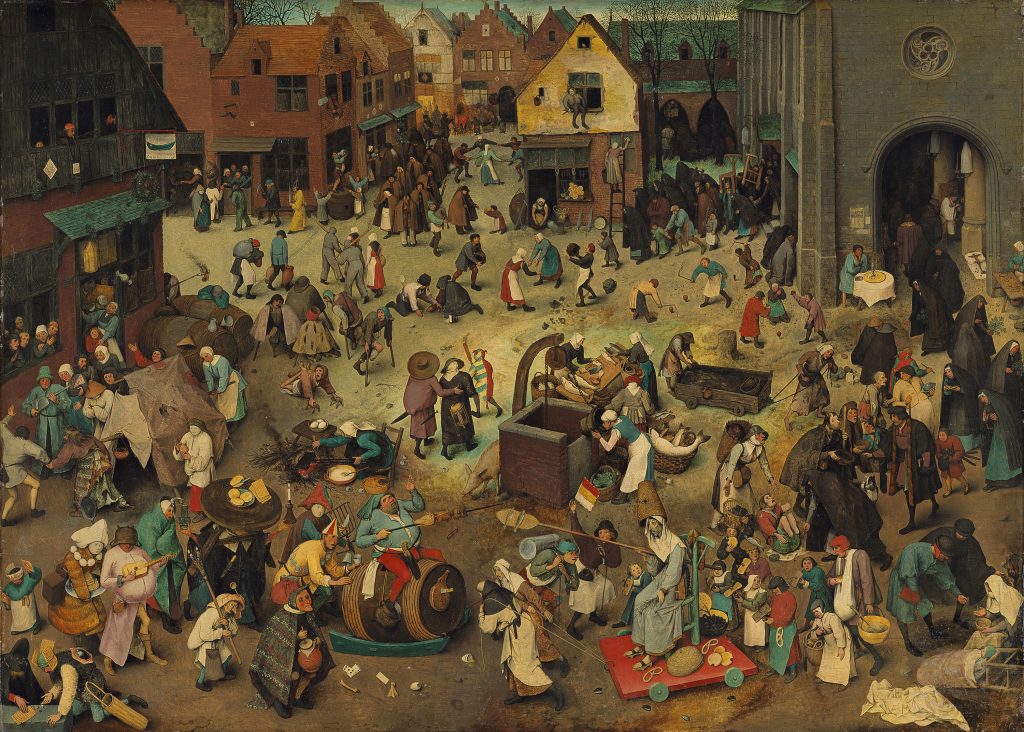

Carnivals were a common sight in Europe in the Middle Ages and the Early Modern Period. During that time, the normal order of life changed: good became evil and vice versa. As Lent approached, people celebrated, ate, and raged. The rich disguised themselves as the poor, and the poor as the rich. Pieter Bruegel the Elder left us one of the best illustrations of this age old tradition in his painting “The Fight Between Carnival and Lent.”

Processions, sacred and secular

“

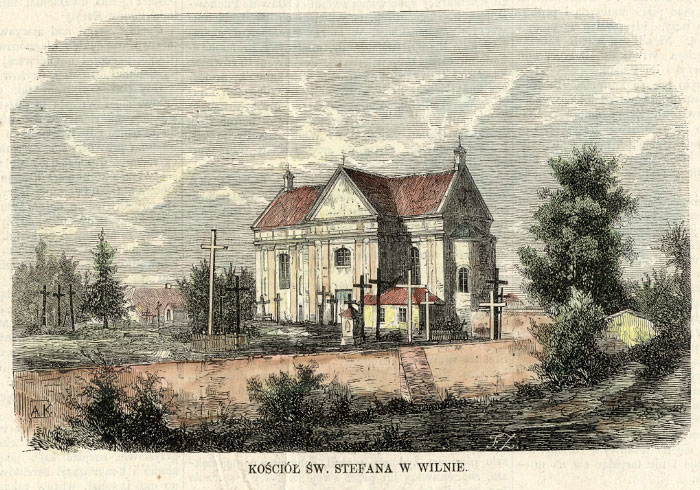

Each guild and association had a banner and individual colours and was obliged to meet at least once a year outside the city walls, “in the fields by St. Stephen’s Church”, for annual inspection.

All kinds of processions were customary in Vilnius, including secular (organised by artisan guilds), religious (for example, Corpus Christi), and ritual (funerals etc.).

In his memoirs, Maciej Vorbek-Lettow, the royal physician to Władysław Vasa, was particularly moved by the Jewish processions in Vilnius. “Jews also gathered with their flag (it was red, with white borders on both sides and many Jewish writings), more than 130 people in all, ready to carry weapons.”

Most likely, the royal physician did not know this was a common occurrence in Vilnius. Each guild and association had a banner and individual colours and was obliged to meet at least once a year outside the city walls, “in the fields by St. Stephen’s Church”, for annual inspection.

Sound of bell, run like hell

Processions also occasioned outbreaks of violence and unrest. In response to this, the Bishop of Vilnius Mikołaj Stefan Pac, raised the matter in his pastoral letter to the parish priests of Vilnius in 1682.

“

We command without fail, that you never carry the Most Holy Sacrament along Jewish Street, rather that you carry the viaticum to the sick through other streets; moreover, the servants assisting the priest are required to ring the bell loudly as a warning for the Jews, so that they might take refuge the more quickly. Those who disobey this command will be severely punished.

“When, here in the city, you carry the viaticum [here: Holy Communion given to those who are dying as a part of the last rites] to the sick going along Jewish Street, a most unseemly custom has already come into use—that of attacks carried out by the persons and Church servants assisting the priest, who are called sacramentalists. They inflict insult upon the Divine Mystery, when, with great license and unheard-of violence, they attack the Jews they encounter: by beating the Jews with whips and other instruments, by overturning the tables they have put out with items for sale, by snatching those things away; and by various buffoonish derisions of Jews and Jewesses, they incite the rabble to laughter and pillage, and they scandalize the pious. Quite often, in order to have a cause for similar license, they purposely give the sign with the bell as quietly as possible, or they even cease ringing the bell entirely, so that the Jews not be given warning and that they be unable to avoid the encounter with them. Therefore, in order to curb such continuing grave abuses, the scandalizing [of the pious], and the in-sult to the Most Holy Sacrament, and for the protection of innocent Jews from damages and harm, We most insistently enjoin, and We command without fail, that you never carry the Most Holy Sacrament along Jewish Street, rather that you carry the viaticum to the sick through other streets; moreover, the servants assisting the priest are required to ring the bell loudly as a warning for the Jews, so that they might take refuge the more quickly. Those who disobey this command will be severely punished. Given in Vilnius, in Our residence in Antakalnis.” (Frick, 2013, 94)

The abovementioned episodes allow for a better understanding of some of the realities in the old Vilnius. The life in the city was dynamic and included various processions, carnivals, celebrations, and riots. The onlookers reacted to those with ridicule, interference, and, occasionally, violence. Secular and spiritual authorities tried to control the people, but their efforts were not always successful.

Povilas Andrius Stepavičius