The Abduction of Helena in Sparta and Lithuania

On 4 September 1636 the Lower Castle of Vilnius hosted the premiere of Il ratto di Helena (The Abduction of Helena), the first opera staged in Vilnius. It was based on a Greek myth, popular in medieval and Baroque Europe, when Trojan Prince Paris kidnapped Helena, the wife of Spartan King Menelaus and so ignited the Trojan War.

The same title would fit the story of the “Lithuanian Helena”, the wife of Grand Duke Alexander Jagiellon. She was also abducted and that sparked a war between Muscovy and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.

Grand duchess, the apostate

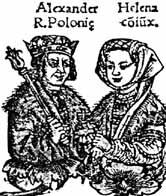

Helena married Alexander Jagiellon in 1495. She was the daughter of Ivan III, the ruler of Muscovy. Their marriage had been set years ago by Alexander’s father, Casimir Jagiellon, in search for peace and dynastic cooperation. The plan met serious obstacles, Alexander had to seek out Pope’s permission, and Ivan III prohibited Helena from converting to Catholicism.

“

In 1501 Alexander was crowned King of Poland, yet Helena, an Orthodox, was not. Many Poles openly called her “the apostate queen.”

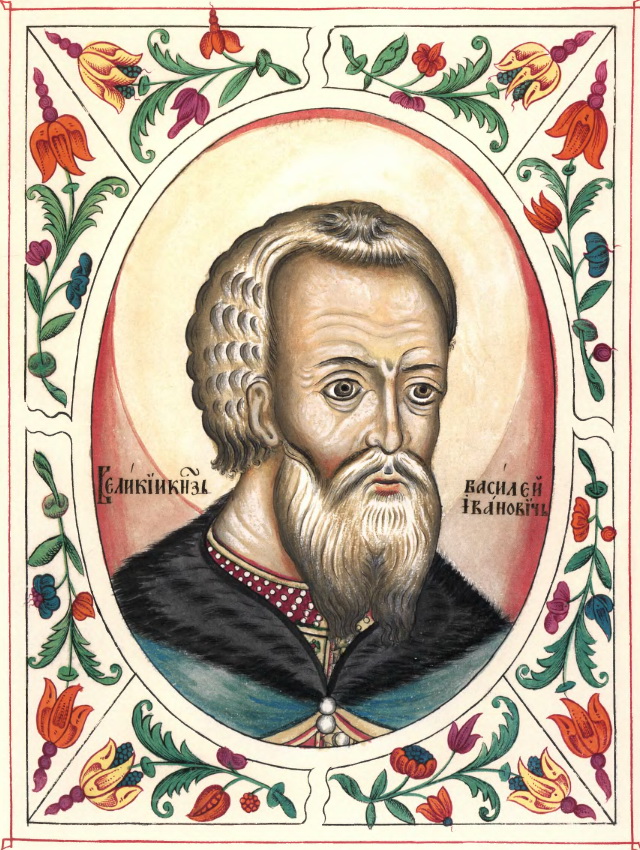

In 1501 Alexander was crowned King of Poland, yet Helena, an Orthodox, was not. Many Poles openly called her “the apostate queen.” All this proved relatively unimportant while Alexander was alive. After his death, in August 1506, the childless thirty-year-old Helena found herself in relative isolation. She was fabulously rich and led a well-functioning court, but lived in the country under constant attack by her brother Vasili III, who took the throne in Moscow in 1505. Moreover, formally, she still was the Grand Duchess of Lithuania.

Luring Helena out

Vasili III conspired to lure Helena to Moscow. In 1512 Vasily’s diplomats went to Poznań to meet the King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania Sigismund the Old. On their way back, they visited Elena, residing in Bielsk Castle at that time. According to the Bernardine Chronicle, “behind the castle, next to the Ruthenian Church, […] she had a treacherous meeting with the envoys, who wanted her to leave for Moscow and at first she ought to reach Braslaw with all her treasures and castles, where Vasily take her under his care.”

Helena was just one of the many nobles who had entrusted their jewels, important documents and other valuables to the monastery. Grand Chancellor of Lithuania Albertas Goštautas wrote in 1525: “There, under the vaults of the Bernardine Monastery, lay the treasures of the whole land.”

The abduction of Helena

The news about Helena’s temptation reached the ears of the most influential magnate in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, Mikołaj II Radziwiłł. The information was leaked by a female worker of Helena’s kitchen, once decried by her lady. Radziwiłł, the voivode of Vilnius and grand chancellor, could not ignore it. Had Helena left the country with her treasures, her brother Vasili III would use a large part of it to finance military campaigns against the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.

According to the Bernardine Chronicle, Radziwiłł warned Helena to stay clear from trouble and then called in four nobles to make sure she stayed in Lithuania. The nobles “grabbed the queen by the sleeve and took her out of the church; then took her to Trakai on sleigh and from there to Birštonas and on to Stakliškės and sent all her people back.”

This gave Vasili III a pretext to resume the war against Lithuania. In the summer of 1512 the Muscovites besieged Smolensk. That time it did not end in their favour.

At the end of the same year Helena travelled to Breslaw, where the wedding of “some noble lady” was to be celebrated. She never came back to Vilnius and died in Breslaw on 25 January 1513. Both the Muscovite and Bernardine sources suggest the duchess was poisoned. The shadow of suspicion fell on Mikołaj II Radziwiłł. He and some other magnates, according to chronicler Jan of Komor, wanted to take over Helena’s fortune.

Helena’s wealth filled the treasury of Sigismund the Old

The Bernardines of Vilnius had a suspicion that Helena’s riches, kept in their monastery, would someday cause trouble. Therefore, in early 1513 they asked that the treasure was documented and then taken to the Lower Castle. The riches were so abundant that it took the whole day for three clerks to list the contents of only one chest. It contained “sixteen thousand silver coins and two thousand golden florins.” Another chest was filled with “pure gold in alloys, jewels and many chains, and sixteen pure gold belts, about four hundred precious rings, four pairs of […] boots inlaid with diamonds and precious stones […]; almost thirty small boxes, one silver, the other gilded, some made of beryl, containing the most expensive alloys and tiaras.”

Upon the arrival of Sigismund the Old, the treasure was handed to him. It took two carriages pulled by sixteen horses to take everything to the Lower Castle.

Eventually, the gold and silver was minted into coins. It is very likely that Sigismund the Old used some of the money to finance the Lithuanian army that crushed the Muscovite forces at Orsha a few months later, on 8 September 1514.

Karolis Čižauskas