Tatars in Old Vilnius: From Warriors to Carters

Few contemporary Vilnans have heard about the Mosque Street [Mečetės gatvė] and perhaps even less are aware of the origin of its name. Up to the late 1960’s the area around present-day institutes of physics and chemistry bore at least two tangible signs of its Muslim past, a mosque and a Tatar cemetery.

They withstood numerous historical calamities, including the so-called Deluge in the mid-17th century, the rebellion of the late 18th century, and the plunder of Napoleon’s retreating army in the winter of 1812. Even after two world wars of the 20th century the mosque and the cemetery remained largely intact. Only under the Soviet rule the cemetery was barbarically desecrated and the wooden mosque demolished in 1968.

The Soviets erased a good part of Vilnius Tatar past.

Tatars and Lukiškės

Do You Know?

According to legend, Tatars played a role in naming today’s Lukiškės district. Sometime at the turn of the 15th century Grand Duke Vytautas the Great took several dozen Tatars on his way back from a military raid in Crimea and supplied them with the land in Vilnius. The size of the area was determined by the flight of two arrows shot from Tatar bows – łuk in Polish. However, Lithuanian Metrica gives a different form and calls it Luka – на Луце in Ruthenian – that could either bear the meaning of a bow or a curve.

Apart from the legends, historians still have no clear answer as to when exactly did the Tatars settle in Lukiškės, then a huge area of Vilnius well outside the city proper. Some theories suggest that they arrived in the late 14th century, others place it at the beginning of the 16th century, as the Mosque was first mentioned in 1558. The former is deemed a little too optimistic, while the latter is overcautious.

There is much reason to believe that Tatars settled in Vilnius and several locales around the capital ‒ Nemėžis, Merešlėnai, and the Village of Forty Tatars ‒ during the reign of Vytautas the Great.

A hamlet rather than a square

Tatars, the widely esteemed warriors, settled next to Neris and were charged with its ford defence. Initially they occupied a rather small area of just several hundred metres across (indeed comparable to the distance that a bow arrow could fly), known as the hamlet of Lukiškės.

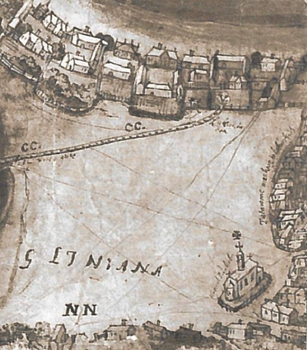

The earliest map of the area was drawn in 1646. It shows the Tatar-inhabited territory next to the St Philip and Jacob Church. The lower edge of the map shows a small gable roofed mosque.

“

The present-day Tatar Street in the Old Town bears the name because it led to so-called Tatar Gate where the road to Lukiškės started.

Over the years, the Tatar settlement expanded along the river and occupied the territory between the church and the present-day Geležinis Vilkas Bridge. Back then, these were suburban areas and no Tatar lived in the city proper. The present-day Tatar Street in the Old Town bears the name because it led to so-called Tatar Gate where the road to Lukiškės started.

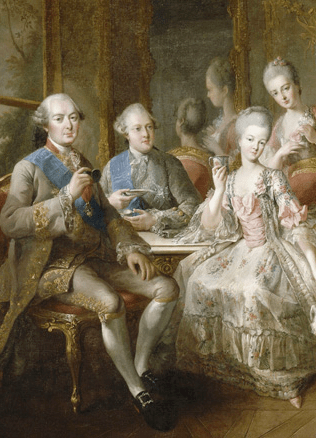

Some visiting foreigners viewed the Tatar settlement in Lukiškės as a peculiar sight, where people “tend their gardens and work as couriers and carters”. But the famous 16th-century atlas, Civitates orbis terrarum (Cities of the world), paints the area in very dark tones: “They work their land or serve as carters and porters; in winter merchants hire locals to take them to surrounding villages in two-wheeled carts. The animals they harness are just like their owners, i.e. tough and cruel. They [the carters] eat crude bread and garlic, live in poverty, and use planks and rocks for pillows.”

About 7,000 Tatars lived in the GDL in the early 16th century, some 200 of them in the settlement of Lukiškės. Most of them inhabited wooden shacks, worked in agriculture and took up various trades. Tatar elite were titled and owned land in exchange for military service.

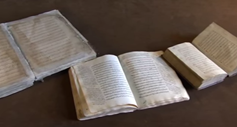

Documented colours of life

The surviving 16th-century documents of the Vilnius Castle Court provide insights into the everyday life of Tatars. Mustafa Bohulewicz Kozel was a merchant, Jach Kulzimanowicz lent petty cash to his neighbours and accepted repayment in labour, Bogdan Muratowicz was a carter rendering services to wealthy residents of Vilnius who sometimes travelled as far as Ukmergė, about 80 kilometres away. One Tatar family wanted their son to become a craftsman and sent him to Kraków where he served a Jewish family for four years.

“

One Ilya Borczekowicz, pressed by his brother Mortuza, stood in court and pledged on his honor to abstain from alcohol for a year. He was to drink nothing else but kvass and water and, in the event of breaking the vow, committed himself to paying a fine to the court and accepting whatever penalty his brother would impose on him.

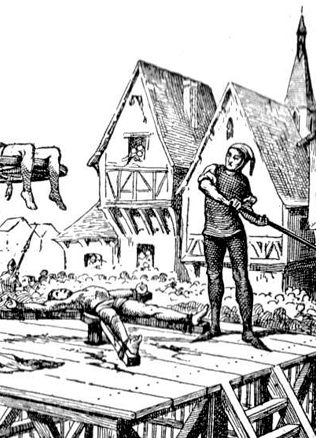

Some sources refer to much more exciting stories. In 1561, four Tatars, armed with bows and arrows, shot, and robbed Tatars Naruset Khodorowicz and three of his friends, while they were returning to Vilnius from a wedding party.

One Ilya Borczekowicz, pressed by his brother Mortuza, stood in court and pledged on his honor to abstain from alcohol for a year. He was to drink nothing else but kvass and water and, in the event of breaking the vow, committed himself to paying a fine to the court and accepting whatever penalty his brother would impose on him.

A Tatar named Tagir chopped to pieces three pigs owned by the wife of the voivode of Vilnius and ran away with a tin container of honey. Ahmet Magmertewicz and his friends beat six other Tatars just outside the city wall and although the victims escaped Ahmet chopped their clothing pieces. Two drunk Tatars stormed a tavern, forced the customers out, and badly injured a woman before robbing her. Mikołaj, a Vilnius-based furrier, lost his chic sable coat and suffered several bruises during an assault on Rūdninkų Street.

The heart of the Muslim area

“

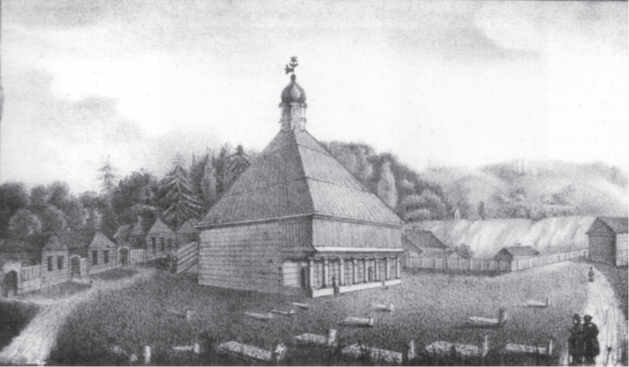

Although several well-to-do families converted to Christianity, the vast majority of Tatars retained their Muslim faith. Their mosque in Lukiškės, apparently built in the fifteenth century but first mentioned in a written document only in 1558, is among the earliest mosques in the GDL.

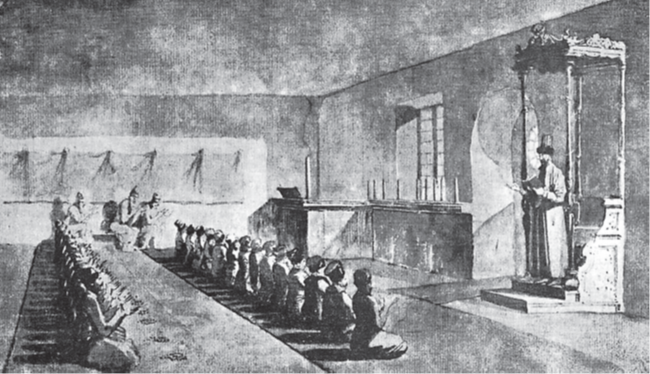

Over time, Tatars developed a unique lifestyle in Lukiškės based on national and religious traditions. Although several well-to-do families converted to Christianity, the vast majority of Tatars retained their Muslim faith. Their mosque in Lukiškės, apparently built in the fifteenth century but first mentioned in a written document only in 1558, is among the earliest mosques in the GDL.

Judging by the surviving images, it was fairly small, built of timber and featured a pyramid-shaped shingle-covered roof topped by an octagonal minaret, its cupola decorated with a crescent and a star. In 1581 an anonymous visitor described the building as rather simple, its interior walls mostly bare, but floor covered with colourful carpets.

The year 1866 saw the start of a year-long major reconstruction of the mosque which also underwent lesser repairs before the end of the century. In the early 20th century, the Tatars mulled over erecting a new brick and stone mosque, their project aborted by the First World War.

From “second-class” people to courtiers

“

As a matter of fact, well-to-do Tatars usually were wealthier than many other nobles in the GDL, yet in terms of their social status Tatars were often considered somewhat inferior. Just like other noblemen, they were obliged to military service, but were not allowed to participate in Sejms. Therefore, they enjoyed some privileges, but not the ones noble did.

The First Statute of Lithuania (1529) banned both Tatars and Jews from witnessing in court hearings and working in Christian homes. More than thirty years on, in 1561 and 1566, royal privileges nullified the restrictions. But even prior to that at least several uncharacteristic episodes were recorded: in 1559 an affluent Tatar Roman Petrowicz had a Christian family (husband, wife and son) in his service.

As a matter of fact, well-to-do Tatars usually were wealthier than many other nobles in the GDL, yet in terms of their social status Tatars were often considered somewhat inferior. Just like other noblemen, they were obliged to military service, but were not allowed to participate in Sejms. Therefore, they enjoyed some privileges, but not the ones noble did.

Tatars fluent in Arabic enjoyed well-paid jobs as translators and interpreters, their demand particularly high whenever the royal court stayed in Vilnius. Archival documents give the name of one of them, Stanisław Hasan. We also know that a Tatar named Milkaman was a royal trumpeter in the middle of the 16th century.

The wealthiest magnates, such as Radziwiłł and Ostrogski, also employed Tatars as their courtiers. One of them, Mikołaj Radziwiłł the Black, had a mansion in Lukiškės.

By Raimonda Ragauskienė