Rector from the Land of Apples

The first Rector of Vilnius University Piotr Skarga (1536‒1612) was born in Grojec, a small town south of Warsaw, famous today for its vast apple orchards that some claim being the largest in Europe. Five centuries ago, this was a godforsaken place in Masovia, a rustic region of Poland. Still today Poles living in big cities joke about Masovians who, believe it or not, stick to their weird mores, get drunk daily, and even talk to bears.

The less caustic commentators acknowledge that Masovian devotion to tradition and Catholic faith were highly resilient and withstood the blows of history. Neither Humanism, nor the Reformation could shake their foundations.

The provincial intellectual

“

Skarga left his father’s mill in his mid-teens and enrolled in Kraków University (1552–1555). Many years later he would recall his professors with gratitude, people who, in his words, laboured to create the image of Christianity daring to face the challenges posed by the Reformation.

Life on a periphery rarely offers a competitive edge. As if knowing this, Skarga left his father’s mill in his mid-teens and enrolled in Kraków University (1552–1555). Many years later he would recall his professors with gratitude, people who, in his words, laboured to create the image of Christianity daring to face the challenges posed by the Reformation. It was Christianity that became Skarga’s life’s path: while still in Kraków, he decided to become a priest.

Appointed a canon in Lviv, he soon became famous for his inspired sermons attended by hundreds. Over several years, he gained fame as an intellectual among the local Catholic elite. In his early thirties he decided to become a Jesuit and left Lviv for Rome, where he underwent the Jesuit spiritual formation. His preparation took two years, instead of the usual twelve, and already in 1571 the new member of the Society of Jesus was sent to serve in Vilnius.

India in Lithuania

“

At the time when dozens of Western European Jesuits travelled to India, China, Japan, and the Americas to spread the word of God. Meanwhile, Piotr Skarga found his India in Vilnius, where he spent eleven years (1573‒1584). The city, just like the entire country, offered plenty of work for a devout Jesuit that Skarga undoubtedly was.

At the time when dozens of Western European Jesuits travelled to India, China, Japan, and the Americas to spread the word of God. Meanwhile, Piotr Skarga found his India in Vilnius, where he spent eleven years (1573‒1584). The city, just like the entire country, offered plenty of work for a devout Jesuit that Skarga undoubtedly was.

Just days after his arrival in Vilnius, on 17 July 1573, he wrote a letter to his superior in Rome. “My heart aches when I see the hardships in this country, where thousands of Catholics have been left without spiritual guidance and the bread they hunger for. Some of them have to travel up to 20 miles to reach Vilnius for a confession. It is frightful to think of the unqualified parish priests and the crowds of infidels. Many of them waver in their faith and would happily return to the Catholic Church if more of us arrived to work here. Let us not seek Indias in the East and the West, because we have one here in Lithuania.”

These words embody the life task Skarga had set for himself: saving souls by bringing people back to the Catholic Church. The multinational Vilnius, inhabited by men and women of different religious allegiances, suited such a mission.

Polemics turned violent

Do You Know?

Once in Vilnius, Skarga engaged in a passionate religious dispute with Andreas Volanus, the most prominent Protestant intellectual of the GDL. The core disputed idea was the understanding of the Eucharist, different in Catholic and Protestant creeds. For us, their theological debate might seem rather abstract and far distant from everyday life. But in the 16th century people of various confessions took interest in the dispute, because its outcome influenced their understanding of what the right balance between the king and his subject should be and which civil laws should be considered appropriate.

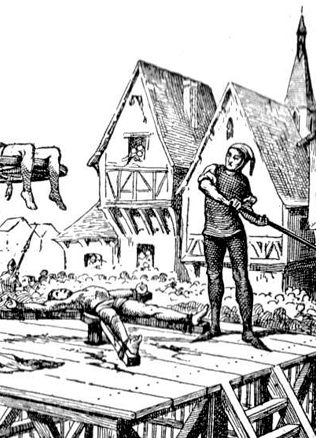

Controversial interpretations of religious doctrines have provoked numerous acts of war and brutality. Skarga also experienced violence in Vilnius. In September 1574, after yet another round of discussion with Volanus, a local Protestant, Albert Seplevski, stopped him on the street and started insulting him, calling him a murderer and deceiver of decent people. Drunk and on horseback, Saplevski threatened to kill him, and hit Skarga’s face. Tensions dissolved as local people started gathering, but the case reached the court of law. Nobleman Seplevski faced the death penalty for assaulting a clergyman, but the parties reconciled, thanks to Skarga’s benevolence.

Unwanted help from Rome

As his private conversations with Volanus continued, often taking place in the house of Catholic Vilnius Wojt Augustinus Rotundus, they grew to become a significant event. Sound of their words echoed in Rome, where one Jesuit dedicated a book written in 1575 aiming to contradict the ideas Volanus was defending. As strange as it may sound, such help brought no joy to Skarga, as it reflected poorly on the local Jesuits, making them look as if they were incapable of defending their doctrine on their own. Skarga reacted to such news writing that “there’s no need to point Roman cannons at one babling Protestant.” Upon considering Skarga’s stance, the heads of the Jesuit Order ceased the publishing process.

It is possible that Skarga declined the help of an Italian Jesuit because he himself was preparing a personal response to all the Protestants in the form of a book, titled “For the Most Holy Eucharist” and published in 1576.

Orthodox people, the next target

Well versed in the Catholic propaganda, Skarga preached in the Jesuit church of St Johns. Both the Protestants and the Orthodox secretly sent their spies to report on what the fiery Jesuit had to say during the sermons. Influential Catholic leaders soon realised that Skarga’s ideas could be useful in the search for the unity of Catholics and Orthodox Churches. Therefore, they persuaded him to write another book. And so “On the Unity of the Church of God” (1577) was the outcome, one of the most captivating polemical texts ever published in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.

“

Influential Catholic leaders soon realised that Skarga’s ideas could be useful in the search for the unity of Catholics and Orthodox Churches. Therefore, they persuaded him to write another book. And so “On the Unity of the Church of God” (1577) was the outcome, one of the most captivating polemical texts ever published in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.

Skarga sought to influence the imaginary audience by analysing cultural history rather than providing a thorough theological argumentation. He ruthlessly scolded the poorly educated Orthodox clergy and even allowed himself an assertion that “none can be educated in the Slavic language.” However, he laid the blame for Ruthenian ignorance with the Greeks. If following their baptism Ruthenians were instructed in the Greek language, they would have seen through the Greek treachery long ago. Therefore, Skarga openly called on the Ruthenians dispose themselves of the anti-Catholic opinions the Greeks passed on to them and embrace a union with Rome.

Polemic explosion and lessons in Polish

Almost immediately “On the Unity of the Church of God” turned into another polemic bomb. Its detonation sent waves so powerful that many wealthy Ruthenians started buying Skarga’s books and burning them.

“

Almost immediately “On the Unity of the Church of God” turned into another polemic bomb. Its detonation sent waves so powerful that many wealthy Ruthenians started buying Skarga’s books and burning them.

A modern reader might deem the polemics extremely fiery, but in the public discourse of the 16th century accusations of heresy were nothing out of the ordinary. More importantly, the polemics were instrumental in cementing Protestant and Catholic self-perception, while urging the Ruthenians to renew their spiritual life.

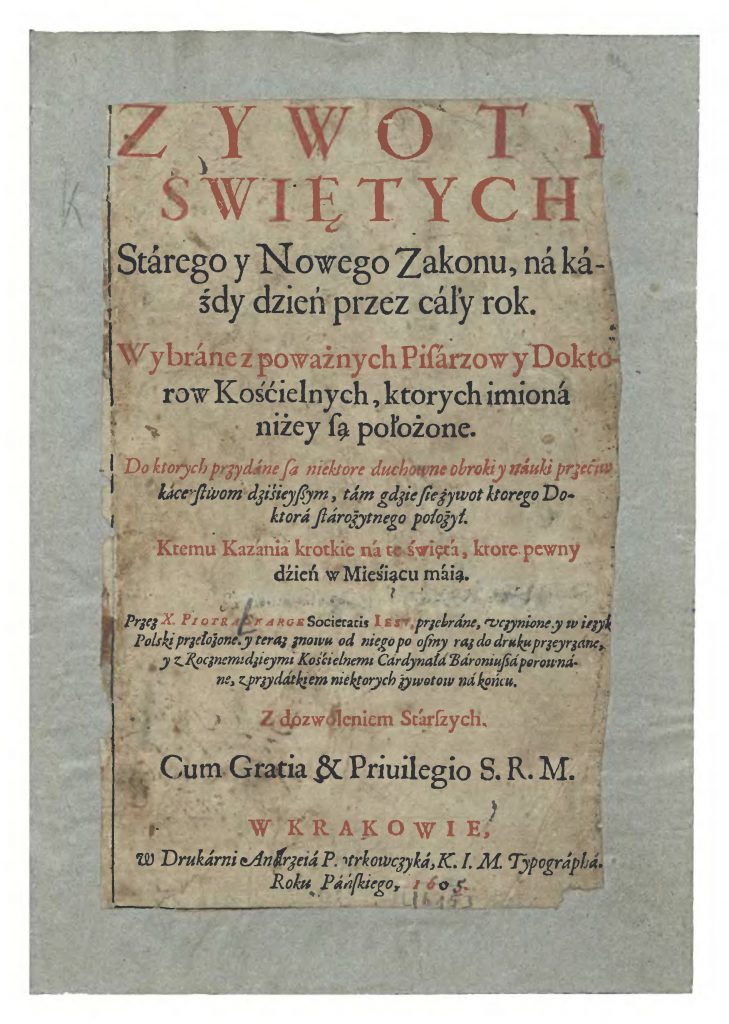

While living in Vilnius, Skarga also did good to the Catholics in Poland, because several generations used his book published in Vilnius “Lives of the Saints” (1579) as a textbook of proper Polish language.

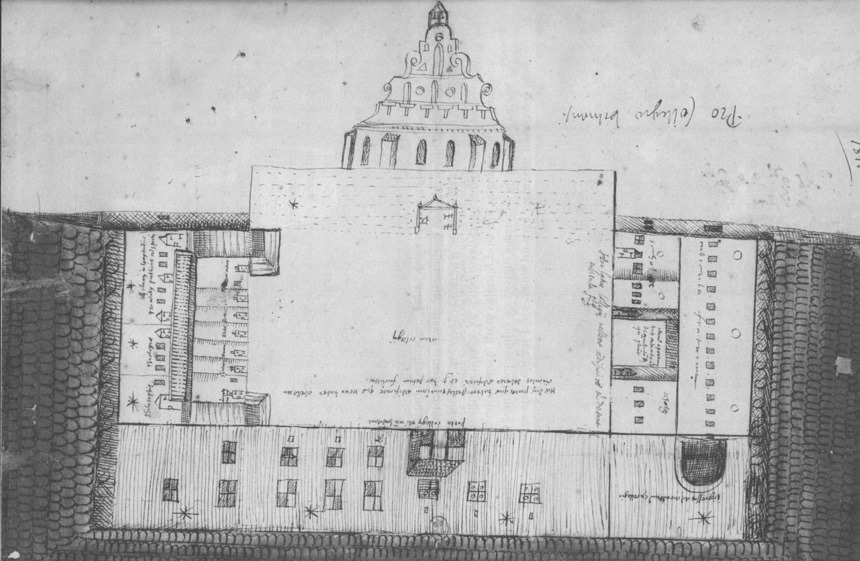

Surprisingly, during their lives in Vilnius two of the greatest Polish authors, Piotr Skarga and Adam Mickiewicz, blossomed. First rector of Vilnius University, though, hardly ever cherished such esteem. He was so immersed in religious and literary life that the managerial duties of a rector (1579–1584) must have been nothing more than a burden. One can easily imagine that Skarga met the news of his dismissal with a smile.

By Darius Baronas