Andrzej Morsztyn, the First Evangelical Resident of Vilnius

In the spring of 1557, a funeral procession passed through the city gate, singing, as Catholics inform us, “godless hymns”, and escorted the body of a wealthy burgher Andrzej Morsztyn to the place of his final rest in the Lukiškės suburb. The procession included Voivode of Vilnius Mikołaj Radziwiłł the Black, several dozen royal courtiers, and Lutheran Vilnans. The surviving correspondence between the Catholic clergy suggests that Andrzej Morsztyn died as a Reformed Evangelical, the fact that prompted Bishop of Vilnius Pawel Holszanski to prohibit his interment in a Catholic cemetery. In the view of the Catholic Church, such rebels as Morsztyn did not deserve a place next to decent Christians.

Even Mikołaj Radziwiłł the Black, one of the most powerful men in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, was unable to overturn the bishop’s decision. Eventually Radziwiłł, an adherent to the Evangelical doctrine himself, “attended the funeral alongside his fellows”, as Bishop of Warmia Stanislaus Hosius attests.

The “heretic” resident of Lukiškės

The Catholic Church deemed Morsztyn a renegade, while history of the Lithuanian Reformation names him one of the first Vilnan Lutherans. He was buried in a family chapel located within the present-day Reformatai Square, part of the huge suburban area of Lukiškės four hundred years ago.

Do You Know?

Lukiškės spanned over a large area alongside Neris between the contemporary Mindaugas and Lazdynai bridges. Some of the most prominent magnate families and wealthy residents of Vilnius held land there.

The remarkable Morsztyn family

“

We know beyond reasonable doubt that the first Morsztyns moved to Vilnius from Kraków, while their ancestors (Morrinsteins, Mornsteyns, Mornstens, Morstens etc.) lived in German lands. In the first half of the 16th century, the Morsztyns already showed up among the political and economic elite of Vilnius. Alongside some of the other families they manage to accumulate power due to their cleverness, wisdom, and riches.

Archival documents offer limited information on the Morsztyn family of Vilnius, therefore few of the questions about them can be answered definitively. Moreover, historiography on them shows several flaws, as some people were mixed up, others were thought to be one and the same person.

We know beyond reasonable doubt that the first Morsztyns moved to Vilnius from Kraków, while their ancestors (Morrinsteins, Mornsteyns, Mornstens, Morstens etc.) lived in German lands. In the first half of the 16th century, the Morsztyns already showed up among the political and economic elite of Vilnius. Alongside some of the other families they manage to accumulate power due to their cleverness, wisdom, and riches.

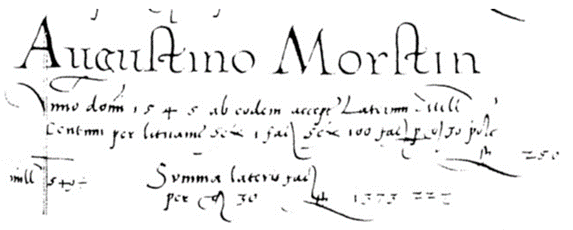

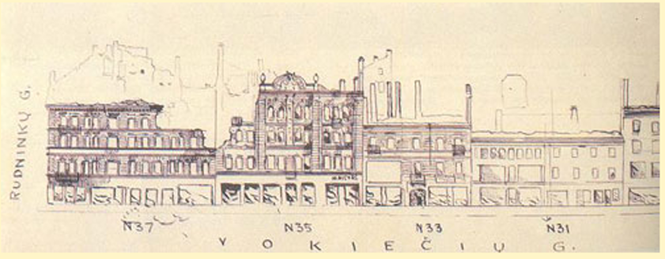

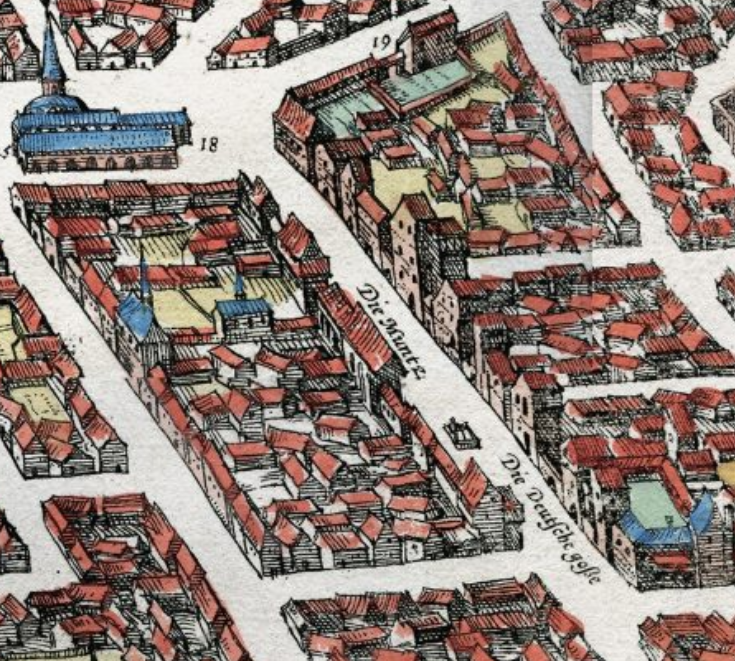

Three generations of the Morsztyns lived in the 16th century Vilnius. The first of them, Augustin Morsztyn, first emerges in historical documents in the 1520s. He was a member of the city council in 1525 and later worked as an assessor, burgomaster, and head of a municipal court of law. He was a wealthy merchant and traded in textiles among other goods with Poland and the East. Quite possibly, he owned several cargo vessels stationed in the river port next to the present-day parliament building. He owned a brick factory that supplied its production during the construction of the Palace of the Grand Dukes. He lived in a luxurious masonry house on Vokiečių [German] Street, owned several plots of land in the city proper, and a country estate outside Vilnius. He was buried in the Church of the Holy Spirit.

Walking in father’s footsteps

Augustin’s son Andrzej first appears in historical documents in 1552. He took over his father’s trade and became a wealthy merchant owning property in and around Vilnius as well as Krakow. His manufactures supplied building materials, ash, and potash. His trading partnerships linked Vilnius with Königsberg. In addition, Andrzej assumed the role of a banker by lending money to aristocrats and the king himself. He maintained friendly ties with many royal courtiers, merchants, and local noblemen, and the urban elites of Vilnius and Kaunas.

Old documents offer several hints that shed light on his religious life. Andrzej was a friend of Jan Radziwiłł, one of the first Lithuanian magnates to adopt the Reformed Evangelical doctrine. Mikołaj Radziwiłł the Black wrote in a letter in July 1550, not without some spite, about his brother Jan, who “roams taverns and Morsztyn’s estates”.

“

Andrzej Morsztyn features a nearly mythological story involving an unidentified Evangelical preacher Wicklef, who arrived in Vilnius in 1555 and the roots of the city’s Lutheran community.

Andrzej Morsztyn features a nearly mythological story involving an unidentified Evangelical preacher Wicklef, who arrived in Vilnius in 1555 and the roots of the city’s Lutheran community. Historian Albert Wijuk Kojalowicz was the first to mention that a certain German named Wicklef was ostensibly banned from preaching in the St Ann’s Church and found a refuge in Morsztyn’s house in the heart of Vilnius. According to Kojalowicz, “by criticising the various Roman practices in loud voice and full force, he had taught his listeners to snub the law that bans eating meat and milk on certain days; […] the poison he offered to the thirsty Germans was enough to spread Luther’s heresy around the city”.

Even today historians of the Reformation have no clear idea who the aforementioned Wicklef was. However, it seems beyond doubt that Andrzej Morsztyn was of the early heralds of the Reformation in Lithuania. For this, he was tried by the city’s Catholic clergy in 1556, but the process never came to a conclusion, because Morsztyn fell ill and died in the spring of 1557.

By Raimonda Ragauskienė