The Wet Gate: From Crucified Martyrs to a Mental Asylum

In the early 16th century, when the Grand Duchy of Lithuania was facing a growing military threat from Muscovites and Crimean Tatars, King Alexander Jagiellon granted residents of Vilnius a royal privilege to fortify the city with a defensive wall to repel the potential attackers. According to the privilege, the wall should feature five gates, all leading to the most important cities. However, this plan was altered in accordance with the demands of everyday life. Therefore, just beside the exquisite Rūdininkai gate that welcomed the arrival of the ruler and the Gate of Dawn, owing its survival to its legendary status, arose a gate not mentioned in the royal plan.

It was known as the Wet Gate or the Gate of Mary Magdalene, because it stood next to the namesake chapel. The gate served no defensive purpose and was built so as to provide the local residents with easier access to the western suburbs of the city. Built without turrets, the gate looked much like a simple hole in the wall.

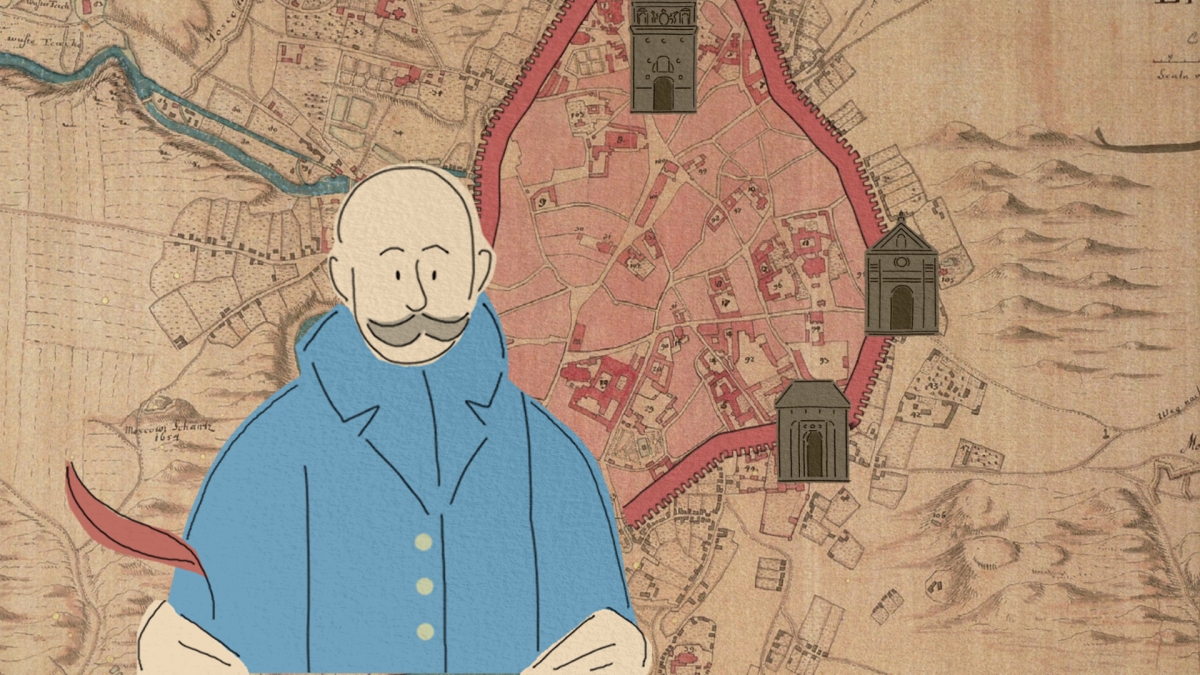

In the heart of Vilnius

According to archaeologists who had spent years examining the remains of the city wall, the Wet Gate stood where nowadays Grand Hotel Kempinski meets the former De Reus Palace (Universiteto St. 10), next to the Presidential Palace.

Its history is fairly short. Built sometime in the middle of the 16th century, the Wet Gate was walled up in 1677, when Vilnius magistrate decided to fortify the weakest links in the wall. It remained unused until the early 19th century, when the Russian tsar ordered an almost complete destruction of the wall.

Do You Know?

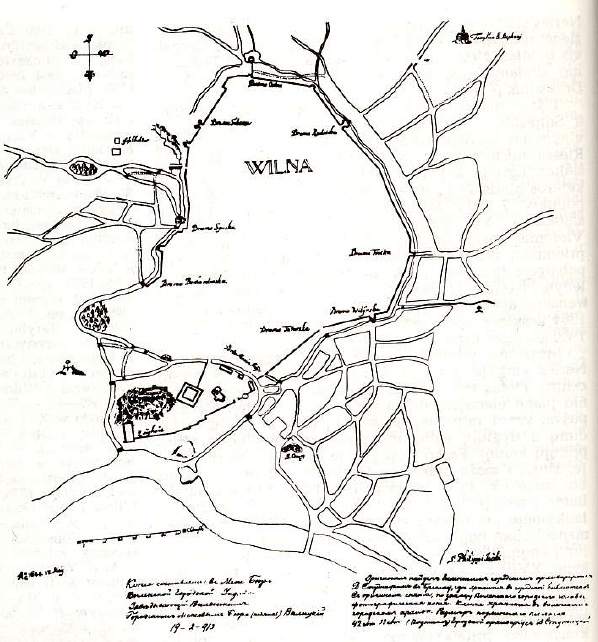

The Wet Gate stood on the territory sacred to the Lithuanian pagan cult. At the premises of the Lower Castle lay the Šventaragis valley where the bodies of the deceased grand dukes were cremated. The valley is thought to have laid between the rivers Neris and Vilnelė, but the riverbed of the latter was considerably changed. Back in the 15th century Vilnelė’s course coincided with Šventaragis and Tadas Vrublevskis streets of today.

Vilnelė flowed beside the walls of the Lower Castle and meandered through at the point where the Wet Gate would later be built. On the opposite side streamed another rivulet, known as Vingrė or Kačerga, winding down the contemporary Bonifratrai Street. This is why the area around the gate was swampy. In the 19th century the rivulet was diverted underground and flowed inside the wooden pipes that were later substituted with brick structures functioning to this day.

Constantly damp and muddy

The confluence of Vingrė and Vilnelė partly affected the configuration of the city wall. When in the 16th century Vilnelė’s course took its modern route, Vingrė continued to supply the city and the Lower Castle with water before becoming Neris’ tributary. Therefore the area between Neris and the Wet Gate was low and damp and could not support any brick structure.

“

When in the 16th century Vilnelė’s course took its modern route, Vingrė continued to supply the city and the Lower Castle with water before becoming Neris’ tributary.

In the mid-19th century Adam Honory Kirkor described the area in these words: “Between the Palace Square and the Cathedral, a quite wide street with wooden pavements takes us to a boulevard stretching towards a suburban Antakalnis district. As the boulevard makes a bend, it reaches the place where previously mud stayed for most of the year, because a rivulet, now diverted underground, incessantly fed the area with its waters that joined with filthy open sewers. Many years ago, a stone and brick gate was there, named the Wet Gate, because the area was always damp and muddy. Beyond it, to the right, a Chapel of Mary Magdalene stood.”

The Christian martyrs

“

But in 1363, when the magnate accompanied Grand Duke Algirdas in an attack on Moscow, dozens of pagan Vilnius residents gathered at Goštautas palace. They were angry at the Franciscans who, apparently, had shown too much fervour in trying to convert the heathens. Tortured and murdered, the friars were eventually tied to wooden crosses and their bodies sent downstream. This drama must have taken place just nearby the Wet Gate would be built, but symbol of their martyrdom became the Three Crosses memorial on the Crooked hill.

The second name of the gate ‒ the gates of St Mary Magdalene ‒ is related to some complicated events of Vilnius history. Back in the 14th century, the territory between the present-day Presidential Palace and the Cathedral belonged to the forefather of the magnate Goštautai family. When Władysław II Jagiełło ascribed the land to the Bishopric of Vilnius, he mentioned the area around the Goštautas’ garden. The Lithuanian Chronicle mentions that during the reign of Grand Duke Algirdas (1345-1377) Goštautas hosted several Franciscan brothers.

But in 1363, when the magnate accompanied Grand Duke Algirdas in an attack on Moscow, dozens of pagan Vilnius residents gathered at Goštautas palace. They were angry at the Franciscans who, apparently, had shown too much fervour in trying to convert the heathens. Tortured and murdered, the friars were eventually tied to wooden crosses and their bodies sent downstream. This drama must have taken place just nearby the Wet Gate would be built, but symbol of their martyrdom became the Three Crosses memorial on the Crooked hill.

The Lithuanian Chronicle describes this event as follows: “While Grand Duke Algirdas marched on Moscow, Voivode of Vilnius Petras Goštautas was at his side. Then many pagan Vilnans congregated and in a large crowd approached the monastery; wishing to be rid of Christians of Roman creed, they burned the monastery down and chopped the bodies of seven monks, another seven they bound to crosses and let them flow down the stream of Neris, saying: ‘since you came from where the sun sets, thence shall you return. Why did you annihilate our gods?’ and in the bishop’s garden, where the pagans dismembered the Franciscans, a wooden cross stands.”

A shelter for mental patients

“

The wettest area of the old Vilnius is still remembered among some local residents and tourists alike who have heard a legend about a miraculous spring that has opened up next to the statue of the Virgin Mary in the basement of the church. Quite understandably, the water there has special healing properties, or at least so the legend goes, and the monks living there still answer questions about the miraculous spring.

After Lithuania eventually adopted Christianity in 1387, the legend of the martyred Franciscans grew more and more popular. When the last descendant of the Goštautai family died in the 1540s, their palace became a part of the Vilnius Bishopry. Nowadays the presidential palace stands there. Bishop of Vilnius Paweł Holszańsky commemorated their martyrdom by erecting a chapel of the Holy Cross beside the palace in 1543. His successor Abraham Woyna invited and settled the Brothers Hospitallers of Saint John of God, known as Fatebenefratelli, that established a hospital nearby their monastery. They tended to the sick and although the hospital was not specialized in a modern sense, its name was associated with the care for people with psychological ailments up to the 19th century. Nowadays it is regarded as the first mental asylum in Vilnius.

The wettest area of the old Vilnius is still remembered among some local residents and tourists alike who have heard a legend about a miraculous spring that has opened up next to the statue of the Virgin Mary in the basement of the church. Quite understandably, the water there has special healing properties, or at least so the legend goes, and the monks living there still answer questions about the miraculous spring.

By Eugenijus Saviščevas