Graves of the Ghosts

Do You Know?

In the 14th century, with an ever-increasing prevalence of Christian burial traditions in Lithuania, the practice of burying the bodies of the deceased was withering away. The dead, traditionally buried in supine position, with the head facing Westward, were laid to rest in the old burial sites, churches or in the territory of churchyards. However, cases are known of the dead being buried with severed heads of limbs in the 14th century and later times.

Mysterious beheaded corpses

A grave of a 45–50-year-old woman, dating back to the 14th century, was unearthed by archaeologists in the Kernavė burial site. The woman was found traditionally laid in supine position, with her feet outstretched. Her skull, however, was turned around and laid in the chest area. The bones of the arms, severed at the elbows, were found between the legs of the deceased woman. Ornate silver-plated earnings were discovered in the area of the ears. The conclusion was drawn that the head and arms had been severed prior to disintegration of the soft tissues. Who was this woman and why was she buried beheaded? The data of archaeological research are not sufficient to answer such questions.

Similar graves were discovered in other burial sites in Lithuania. During the archaeological dig of the interior of the church of St. Anne, located in the territory of the Vilnius Lower Castle, a dead skeleton, the head of which was severed and placed under the shoulders, was discovered. In several graves of the Alytus burial site the skulls were found “not in the place where they should be” or there were no skulls to be seen. In the Baltic countries, the graves with the skulls placed by the side of the skeleton, were discovered in Prussia, in the 13th century Vėluva burial site. Archaeological research authors relate these graves to ostensibly pagan burial rituals, which reflect the struggle with vampires among the baptised Prussians.

The archaeological data suggest that a custom was observed in the 18th century to decapitate the heads of the perceived vampires and placed the between the legs in the hope that the vampires would not harm the living.

A reference to the Prussian Code of Law, provided by the archaeologist Eugenijus Svetikas, should be cited in this context, saying that “decapitating or severing a dead person’s head is an offence, repayable with half a mark.” There is some mention of the existence of such a rite in Lithuania as late as in interwar press, with stories told about beheaded vampires.

The return of the wicked and those who took their own lives

Usually burial rites and rituals were meant to flatter the deceased, seeking peace for both the dead person and the living. However, in the above-mentioned cases, a negative attitude toward the deceased can be discerned. There is little likelihood, if any, of execution in these cases, as an act of punishment for the sins unknown to us. This hypothesis is proven by the fact that at first the dead were neatly buried alongside the other members of the community. A beheaded woman in Kernavė was adorned with ornate earnings.

Another reason for explaining the rite of beheading the dead could be related to the necrophobic nature of beliefs and rituals, which abound in our mythological legends and stories. The dead are believed to sometimes have come back to intimidate and harm the living in various ways. In such cases, the dead person would be exhumated and decapitated. The Lithuanians had plenty of names for such apparitions, like vaiduliai, vaiduokliai, vaidinuokliai, velioniai, nelaikiai, prisidavėjai, kraujasiurbiai or vampires. The names in most cases were used to describe the persons who died not of natural causes, in an accident, who were murdered of committed suicide (particularly those who hanged themselves), offenders and sinners, magicians and infidels.

The deceased people who keep coming back in those stories were usually regarded as negative personalities in real life, described as: an angry landlord, a wicked person, having an obsession with vodka, the one who died without a priest, never made confessions, a fallen woman hanging out with the devil….

War axe against apparitions

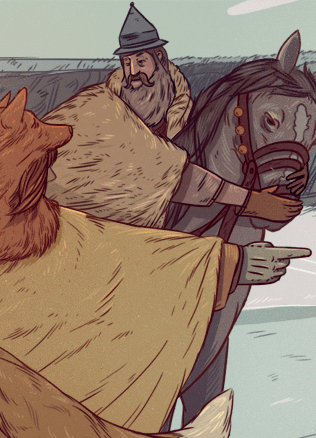

According to the legends, the restless and haunting body of the deceased was unearthed and beheaded by a specially hired person, with a lot of experience in this particular “business.” Decapitation was performed not in any seemingly random manner, but “backward swing”. A decapitated head was placed between the legs of the deceased person to make sure that he/she cannot reach it and put it back, in the place where the head belonged. There is an abundance of narratives, in which parishioners are given such advice by the priest, who instructs them to protect themselves in such a manner against being haunted by apparitions. According to Jonas Balys, who is known to have collected a number of such stories “this was not a Lithuanian invention; however, such an atrocious measure seems to have actually been resorted to in our country not that long ago.”

The faith in bloodsuckers and vampires is regarded by Jonas Balys not as local practice but taken over from Slavic culture.

The Slavic origin of vampirism as a form of necrophobia is recognized even today. In scanty Lithuanian narratives about bloodsuckers and vampires there is no mention of decapitation practice or of their burial rites as such. Therefore, there are no reasonable grounds for relating the decapitated bodies of the deceased individuals identified during archaeological digs to these mystical creatures. In the Lithuanian stories and even mythological legends, this ritual was performed merely to the deceased persons who kept haunting the living, in most cases those who did not die of natural causes, who committed suicide or lived as sinners. The bodies of deceased persons whose heads were cut off or limbs severed, should be related not to burial rites but to exhumation and defiling of corpses, caused by the fear of being haunted by the deceased person in question. Thus, the grave of the decapitated woman is a ritual illustrating the struggle against being haunted by the deceased persons, caused by necrophobia.

Gintautas Vėlius