Medieval Pastor – a Neighbour Holding the Mass

If you happened to be walking along the town of Ramygala in the 15th or 16th centuries, you could pass a local vicar or pastor without even suspecting that a priest went past. At that time priests’ apparel and way of life in GDL, as in the whole of Europe, was quite similar to those of the laity. In the Middle Ages, the most important distinguishing sign of priests and monks was a tonsure, that is, shaving some or all of the hair on the scalp. However, priests preferred wearing a hairstyle of the nobles, rather than a bald scalp as a sign of religious humility or devotion. Even if they chose to have a tonsure, it was so tiny that it was practically unnoticeable to the people surrounding them. A cassock, a special robe worn by priests, came into existence only in the late 16th century. Up till then, priests were required to wear neat and modest clothes. To illustrate the point, a ban is found in the resolutions of the Vilnius Synod (1527) for the clergy to dress in multi-coloured and striped clothes, adorned with fringes. The resolutions also specify that priests were to be clad in a full-length robe. In holy places, particularly during mass sacrifice, they were not to appear before their congregation in clothing revealing their naked shins.

Do You Know?

One of the most important attributes of priesthood – a careful observance of celibacy – was also treated offhandedly. If the aforementioned Ramygala pastor had been asked what his relationship with the woman living in the parsonage was, he would have repudiated any alleged relationship. However, the more talkative residents would have most likely narrated a different story about the priest’s personal life, giving all the details about the woman’s service time, the number of children he fathered, etc. Parish members would have become indignant if their pastor had challenged the common moral values, e.g., been cohabitating with a married woman, shown violent behaviour, neglected his offspring, etc. One of the explanations why the clergy reminded more of noblemen than priests proper was that the majority of them were of noble origin and thus reluctant to renounce the old way of life. The social and political life in GDL was dominated by the gentry, whereas the peasants were increasingly subjected to serfdom. Due to these reasons, the number of priests coming from the peasantry or town setting was very insignificant.

Remote priesthood

Yet another important factor shedding some light on the issue of a free way of life among the clergy was that up till the late 16th century bishops showed little interest in the profile of priests serving in the parishes of their diocese. Ordinaries usually appointed a priest proposed by church patrons as a parson. As was the case with many other ecclesiastic and secular services, parishes were granted for life-long service. Only in extreme cases would bishops exercise their right to deprive a member of the clergy from performing his ministerial duties.

From the mid-16th century onwards there was a slight chance of bumping into a parson in Ramygala. This parish of Vilnius diocese was rich, and therefore reserved only for high-ranking clergymen, such as members of Vilnius Cathedral Chapter or even bishops.

In the 16th century, a trend to reserve the richest parishes for the highest clergymen became more and more pronounced.

Individual cases are known, when a certain parish priest never showed up in his parish, e.g., Stanislaw Klodzinski, who had been entrusted with the care of the Ramygala parish in 1569–1575, was working in Italy as Sigismund Augustus’ diplomat and never even bothered to visit Lithuania.

Do You Know?

The absence of a parson did not mean that parish members were not provided spiritual services. In such cases this was the care of a vicar, who was paid a meagre wage, agreed upon with a parson. It is not surprising that very few vicars were known to have had an exceptional zeal for pastoral work. The situation of vicars was similar to that of other hired workers. In case of disagreement with an employer, most often than not vicars would leave to seek work in other parishes. Seldom would vicars stay in one parish for a long time.

Peasant priest

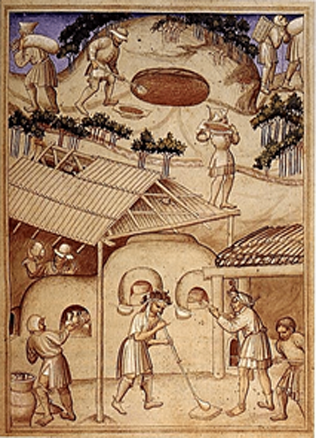

The parsons of the Siesikai and Traupis churches, situated in the neighbourhood of Ramygala and granted inadequate provision, were not that well educated. Yet they still lived next to their churches and performed priestly duties. The number of services to be provided was not that big – only in larger parishes religious services had to be held several times a week, sermons did not have to be prepared because they were needed only in exceptional cases, infant baptism was usually conducted in places frequented by priests, such as a parsonage or even a pub. Townsfolk and peasants would often be wed in church, whereas the gentry would invite a parson to their house. It was not the usual practice to ask a priest to come for extreme unction. The remaining part of the time was used by parsons as by other landlords. They took care of their economy, spent their leisure with relatives (in case they lived in the proximity) and friends.

Even though a parson did not own the property of the church, he could use and manage it.

Every church had its own “provision package,” the most important element of which was the land.

Furthermore, tithing, pubs, in-kind and monetary tribute could also make part of it, to a lesser extent the right to fish or cut forest, mills, market fees and the like could be included into the package. During the evaluation of the wealth of churches and pastors, first and foremost consideration was given to the amount of land tenure, which did vary. For example, the Ramygala church owned 101 dūmas (small peasant tenements as tax units), Siesikai church owned 8 units, and Traupis church – merely 3. Parsons, particularly non-resident parsons, avoided any economic concerns, if they leased church property, or part of it.

Do You Know?

The gap between the wealthiest and the most wretched parish parsons was best reflected by the residence trends and parsons’ level of education rather than by income inequality. Even though most of them were part of the intellectual elite, it was of little benefit to believers. Actually, they never saw their parson.

Imported clergy

Up until the 16th century, there were no seminars or other educational institutions training clergymen, therefore the young men seeking to pursue a clergyman’s career, usually attended parish and/or cathedral schools; some of them went to university. Having acquired university-level scholarly degrees, clergymen usually sought higher ecclesiastical career, looking upon parishes as an additional source of income. Ordinary pastors would simply pick the relevant knowledge from another pastor.

During the first centuries following baptism, priests from Poland would come to GDL. Immigration of clergymen from a country having deeper Catholic traditions to a newly baptized country was a common phenomenon in Europe. Lithuanians succeeded in defending bishops’ thrones against alien competition. However, there was not enough local clergy to oust Polish priests from parishes.

During the period in question the clergy of Polish origin accounted for about one half of the parish clergy.

They tried to learn the local language to the extent they needed, in order to create the social environment and manage domestic affairs. In Vilnius diocese, the first clergy of Lithuanian origin started working in parishes in the first half of the 15th century, whereas in the Samogitian diocese this trend became apparent in the second half of the 15th century.

Do You Know?

A parish parson of the 15th-16th century GDL had little to do with the image of a contemporary Catholic priest. A person of modern times would find it difficult not only to recognize a parson walking along a street but also to fathom such discrepancies in income, education or ethnic origin of adjacent parish parsons. However, this variety did not hamper the existence of shared estate consciousness among the clergy.

Reda Bružaitė