The First Autobiography in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania: Teodoras Jevlašauskis

Teodoras Jevlašauskis (Fiodor Jevlašovskij, February 8, 1546 – after 1619) was a lesser noble of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, coming of Ruthenian descent, whose manuscript text in the Ruthenian language, created in the second half of the 16th – beginning of the 17th century is regarded as the first autobiography in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania (a copy of the manuscript was discovered in the mid-19th century in Lvov). The original autograph of the manuscript, stored in the Archives of Ancient Acts in Warsaw (AGAD), was found only in the second half of the 20th century. During the period of the 19th-20th centuries, the text by Teodoras Jevlašauskis was released in the Polish, Ruthenian and English languages. In 1998, Atsiminimai (Recollections by Teodoras Jevlašauskis) were published in the Lithuanian language (in the surviving autograph, the beginning of the text and the possible title are missing). The work Atsiminimai by Teodoras Jevlašauskis, created in the form of memoirs but permeated with an apparent underlying intention of an autobiography and self-reflection, provides basic information about the author. At the same time, the aforementioned piece of work is a unique work of literature, a rare and most valuable source, enabling us to cognize the consciousness and mindset of a lesser noble, living in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania in the second half of the 16th century.

Life-story and dreams

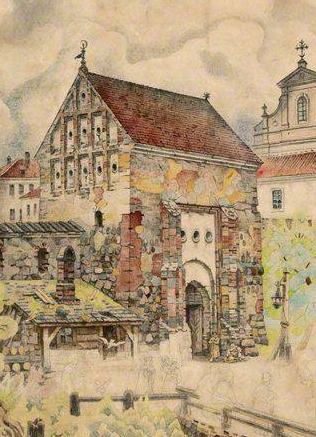

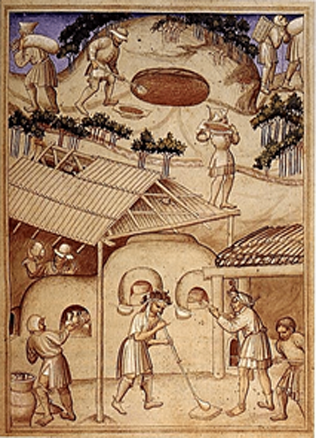

Teodoras Jevlašauskis was born in Lyakhavichy, surrounded by the historically significant vicinities of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania (Nowogrodek, Mir, Slutsk and Slonim). Lyakhavichy, in which the residence of Teodoras’ parents (a Russian Orthodox priest Michail Liavonovich and his wife Fedora) was situated and which was often visited by Teodoras, and Vilnius, in which a nineteen-year old youth settled, are the main geographical centres identified in his memories, with which the author seems to have been glued together by the strong emotional bonds of attachment. During his lifespan, Teodoras Jevlašauskis never travelled beyond the borders of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and Poland, even if he cherished dreams of visiting Hungary and Turkey. As mentioned in his recollections, his family commitments (guardianship of his brothers and sisters) after the parental bereavement tied a young man, still under thirty, down to “these parts of the world.” The dream to travel was over time realized by his son Joachim, who thanks to his father’s contacts got a position in the court of the Duke of Mantua, Italy. Higher education was also a dream that never came true. Teodoras Jevlašauskis completed only basic studies and, having acquired skills of writing in Ruthenian and Polish languages, as well as the skills to perform basic arithmetic computations and record keeping, started to work in 1565 in Vilnius collecting the Community Charge (the so-called Poll Tax). Later in life he served the Radziwiłł and Chodkiewicz families, the magnates of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. It is worth mentioning that 1572 the latter came into possession of the Liachovičiai, the birthplace of Teodoras Jevlašauskis. He is also known to have served in the Vilnius Court of King Sigismund Augustus. In 1577, King Stephen Báthory granted Teodoras Jevlašauskis the position of a bridge-builder in Pinsk and Servech. As a representative of the nobility of the Navahrudak district, Teodoras Jevlašauskis took part in the Seimas activities and was member of the Commission, established to develop the High Tribunal Statute of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. From 1584, Teodoras Jevlašauskis was appointed instigator of Vilnius. In 1592, he was granted by his patron Alexander Chodkiewicz the position of a pre-lawyer at the territorial Land Court of Navahrudak, which he held until his death.

During his lifespan, Teodoras Jevlašauskis remained faithful to the nobles he was serving. He maintained contact with an outstanding personality of the second half of the 16th century, his contemporary Mikołaj Krzystof Radziwiłł the Orphan, the oldest son of Mikołaj Radziwiłł the Black. It is highly probable that the success and popularity of the memoirs, entitled Journey to Jerusalem, written by Mikołaj Radziwiłł the Orphan, could have served as a source of inspiration to Teodoras Jevlasauskas and encouraged him to start writing.

Marital happiness and personal grief

In 1577, Teodoras Jevlašauskis married an Orthodox Hanna Bolotovna. His recollections are permeated with the narratives related to his family and private life (according to the evidence left by Jevlašauskis in 1604, he was a father of nine sons and five daughters). The poet loved his wife and children and was infinitely proud of them. This is the quote from his memoirs about his wife: “…she never made my life bitter, being of male spirit both in the activities of daily living and in ailment; she was also of great virtue, with her heart never giving way to vanity or evil thoughts.” All the children are believed to have survived and grown up, which was a rare case in the 16th century). However, in 1602 Teodoras Jevlašauskis was overwhelmed with grief when his son Jonas was killed under mysterious circumstances. The narrative about the son’s death and funeral is regarded as the culmination of the Atsiminimai (Eng. Recollections).

Never prior to that tragic event having judged people, the poet describes the personal tragedy with bitterness, resignation and distrust: “May the Lord, the righteous Judge, repay them in keeping for their deeds and sins; when I was struck with this tragedy, the people around, who had previously posed for my friends, dropped their masks, revealing their infidel faces and were more than willing to sting me with their lethal poisonous venom.”

Worldview born in a multiconfessional environment

One of the most impressive aspects of the Recollections by Teodoras Jevlašauskis is his unique style of narration. Never having been exposed to the impact of the high literature and having read merely a few books in Polish and Ruthenian languages (mostly of religious nature) as a product of the book publishing activities which started in Lithuania in the mid-16th century, possibly having laid his hands on some Bible or Chronicle and having managed record-keeping of domestic policy, Teodoras Jevlašauskis’ style of writing was based not on the models characteristic of classical rhetoric. Seeking to express his ideas, the poet chose the language which conveyed his authentic thinking. Notwithstanding certain nuances of chronicle-type narrative and the trends emulating the wording of religious texts, the Recollections created by Teodoras Jevlašauskis stand out in the context of creative writing of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania by the depth of personal experience and expression of intense feelings. A singular and colourful confessional identity of the writer adds uniqueness to his otherwise religious and even superstitious style of writing. Even though Teodoras Jevlašauskis was an Orthodox who chose to convert to Protestantism, the abundance of thoughts based on religious reasoning (the relationship between God and man was of great interest and excitement to him) is sufficient proof that during the entire life-span, his religious mindset covered not only such issues as the habits, images and way of thinking characteristic of the Ruthenian-Orthodox tradition, but even those of the Catholicism prevailing in Lithuania at that time (e.g., deep respect for the Pope, hierarchy of the Catholic church, the Sacraments and other sacred Christian rites). At the beginning of the Recollections, Teodoras Jevlašauskis highlights the fact that in his youth, upon coming to Vilnius in 1566, he was listening “to the word of God, preached by educated ministers” in the “Christian gathering” of the Protestant community. Under the influence of the Reformation, which flourished in Vilnius in the fifties of the 16th century, and during the period of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, religious conversions were undergone by many representatives of the Lithuanian lesser nobility. The testimony provided by Teodoras Jevlašauskis demonstrates the aspects characteristic of the nobility’s religiosity in the 16th century. Having embarked on the path of Protestantism, an ordinary representative of lesser nobility could not tell the difference between various doctrinal features of Protestantism movement. Instead, he was attracted by Evangelical openness, enthusiasm, freedom to attend innovative religious services and thus express a personal relationship with God (“I had great fun there”). It was namely in 1566 that the Lithuanian Evangelical Church experienced a schism and as a result was divided into the two religious communities” that of the moderate Reformers, and the radical Antirinitarians. Teodoras Jevlašauskis never identified his confessional preference. The multilayered confessional mentality of the poet is also demonstrated by the fact that it is uncertain whether he realized having joined the activities of the community of an Antitrinitarian nature, which started to develop at that period, and not the community of Reformed Evangelists (Calvinists). This is evidenced by the names of historic persons, known to have joined the side of the Antitrinitarians during the period in question, mentioned by the poet. After many years, the sermon during his son’s funeral was delivered by the Unitarian preacher Jonas Licinijus Namislovijus, who apparently fell short of Teodoras Jevlašauskis’ expectations.

The world as seen by the noble living in the 16th century

The main storyline underlying the Recollections is related to the author’s wish to highlight the story of his personal life, therefore side by side with the portrayal of his career line he focuses on the personal life, not even disguising certain diseases or seizures of “eyesight impairment.” Teodoras Jevlašauskis mostly concerned with self-reflection. He compares his behaviour and accomplishments with the surrounding environment and the lives of other persons, providing his own assessment and even presenting the deeds accomplished by himself, “a mere little bug in the eyes of God.” A distinctive feature of the structure of Recollections is highlighting the sequence of time. The narrative is framed by descriptions or mere mentioning of deaths.

Jevlašauskis was the first in the Lithuanian literature to have described suicides caused by depression (that he calls melancholy) and the stories of predicted deaths which came true.

Even though not having acquired exceptional education, he was sensitive enough to reflect upon existence and the relationship between life and death. The poet explained most of the deaths as a mysterious and unfathomable but fair plan, implemented by God, interpreting thus both life and death as the forms of evaluating one’s merits or punishment.

Literature: Teodoras Jevlašauskis, Atsiminimai, Vilnius: Lietuvių literatūros ir tautosakos institutas, 1998.

Dainora Pociūtė