The Lithuanian Chronicles

Lithuanian chronicles are historiographic anonymous creative works, in which the history of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania is described. In them, a pragmatic coherent narration goes hand in hand with the notes referring to a specific year. The Lithuanian chronicles are written in the Ruthenian language of the 14th-16th centuries. According to the content described and the date of creation, Lithuanian chronicles can be classified into three redactions (the major redactions).

Laudation to Vytautas

The short redaction of the chronicles (annals) was compiled around 1446. The chronicler was based in the Cathedral of the Orthodox Bishop in Smolensk, which then was part of Lithuania. The genesis of the redaction is of major interest, since its compilation is related to the coronation aspirations, cherished by Vytautas, the Grand Duke of Lithuania. The redaction consists of two parts, namely, the Russian part and The Chronicle of the Grand Dukes of Lithuania (Летописец великих князей литовских). Its origin can be traced to the memorial dictated by Vytautas the Great, who by the end of 1389 had retreated to the German Order, the so-called “Vytautas’ complaint.” At a later time in history, a narrative was composed in the Court of Vilnius on the basis of the aforementioned memorial about the conflict between Władysław II Jagiełło and Vytautas’ father Kęstutis, resulting in the latter’s death. The narrative also included the description of Vytautas’ struggle for power and his aspirations to gain a foothold in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. Still later, an additional narrative about Lithuania’s subjugation of the Podolian lands and the loss of the western part of this province upon Vytautas’ death (1430), was written. The last stage of compiling the redaction is usually related to the environment of the Orthodox Metropolitan Gerasim († 1435), Bishop of Smolensk and an old ally of Vytautas. Relying on the abovementioned sources of information, in 1428 the Bishop’s clerk Timofei created the primary version of laudation (Russ. похвала) to Vytautas. This version served as a basis for a more comprehensive and ceremonial laudation to Vytautas, created in 1429–1430 and incorporated into the ‘Russian’ part of the redaction.

The aforementioned part is a compilation of Russian chronicles, composed with the aim of removing any anti-Lithuanian assessment from the information provided. Chronologically it comprises the Russian stage of history from the first semi-legendary warriors, the Varagian Dukes up to 1446; its last part mostly consists of the information and narratives written in Smolensk, therefore researchers usually look upon “The Chronicle of Smolensk” as a separate piece of the redaction. Of special interest are the original narratives of “the Chronicle” about the dramatic internal war waged in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania in the 30-ies of the 15th century between Švitrigaila and Žygimantas (1432–1436) and the uprising launched in Smolensk after Sigismund was killed in 1440. Even though a lot of space is allocated to describe Švitrigaila’s military actions, it is obvious that the chronicler supports the side of Vytautas and his brother Žygimantas. On the other hand, Algirdas is being judged and condemned, and his defeat in the Battle of Pabaisk (1435) is interpreted as God’s punishment for having put Metropolitan Gerasim at the stake.

The culmination of the redaction in question is the Eulogy (похвала) to Vytautas.

In it, Vytautas is described as the most prominent ruler of his time, without an equal in quality or extent, hardly comparable to the other rulers governing the lands around, “from sea to sea.” Upon his orders, Holy Roman Emperor Sigismund came to Lutsk, and even Russian princes obeyed him. At his will, Chans of the Golden Horde were given the throne. On the other hand, in the Russian part of the Chronicles, the history of the Northern East Russia and Principality of Moscow is highlighted. The intentions of the chronicler are quite obvious, reflecting the aspirations of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and Metropoly of Smolensk to manoeuvre between the two mighty powers existing in Russia at that time. From the ideological point of view, the redaction, based on various sources, is a controversial piece of work. However, given the circumstances of its appearance, this should not be surprising. The abovementioned contradictions were eliminated during another stage of Lithuanian historiography, the stage which developed and matured under different circumstances.

A mythical history of the nobility

With the emerging threat from Moscow and the ever increasing political pressure from Poland, two new redactions were compiled in the first half of the 16th century in the court of Voivode of Vilnius and Chancellor of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania Albertas Goštautas († 1539), the so-called Middle and the Extensive (the Bychowiec Chronicle). Both of them embody the ideology of the then elite of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. The Russian part of the Short Compendium was replaced by a mythical prehistory of Lithuania, in which the origins of the Lithuanian nobility are traced back to the noble Romans who fled from Rome in ancient times. According to the authors of the Middle Compendium, the ancestors of Lithuanian dukes and noblemen fled from the persecution of Emperor Nero in the 1st century AD, whereas the Bychowiec Chronicle provides another interpretation: the ancestors of Lithuanian dukes and nobility had to flee from the furious and notorious Hun leader Attila, called “the Scourge of God” in the 5th century AD. A detailed description is provided in this redaction about the establishment of the state and its extension into the Russian lands (occupation of Navahrudak, Polotsk and Kiev) and a fanciful genealogy of the rulers from the legendary Duke Palemon, who had escaped from the Roman Empire, settled at the mouth of Dubysa and founded the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, up to the times of the Grand Dukes Vytenis and Gediminas, is narrated. The remaining part of the material, inherited from the Short Redaction, is revised and supplemented.

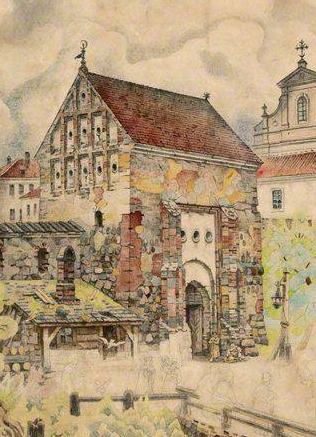

This is how the first history of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania was created, starting with the legendary times and covering the entire period up to the mid-15th century (in the Bychowiec Chronicle, the period covered was up to the beginning of the 16th century, that is, up to the lifetime of the chronicler, whereas The Chronicle of the Grand Dukes of Lithuania together with the narrative about the Podolian lands covered merely less than a centenary of the state existence). Thus, even though modern historians discount part of the texts as useless, the three redactions of Chronicles provided useful bits and pieces of Lithuanian history. These were the first known historical accounts produced within the Grand Duchy, giving rise to the historiography of Lithuania. The very name of Lithuania found its way into history through the aforementioned Chronicles, with the description of its beginning and origins provided in them. Furthermore, the Chronicles contributed toward making the name of Lithuania known far beyond its borders. The Chronicles made it possible to relate Lithuania to the global history. In them, a narrative is given of how the territory of the state was formed and how the capital of Vilnius was founded. Among the most memorable episodes is an impressive narrative about the hunting of the Grand Duke Gediminas and his prophetic dream at night, the meaning of which was explained by the High Priest Lizdeika. The huge howling iron wolf, seen by the Ruler during his dream, could only signify the glory of the future capital. In the Chronicles, like in all old historiography as such, a lot of focus is placed on the genealogy of the rulers.

Having perused both the Middle and Bychowiec Chronicles, one gets an impression of a continuous improvement, even to the point of polishing the material presented.

New genealogical links are inserted into the legendary genealogy of the Lithuanian rulers. In the Bychowiec Chronicle, Mindaugas, the first historical ruler of Lithuania, and his son Vaišelga appear on the stage. The very fact that three dynasties replace each other in this genealogy, the last one of which is not even related by blood ties with the previous dynasties, could remind us of the classical Western model (comp. with the three French dynasties). A trinomial scheme like this does not create such an “ecclesiastical” image of monarchy, as the one presented by the writings of the competing Moscow. On the contrary, the origin of the Gediminids and the noblemen Goštautai is traced back to the Roman aristocrats. This bespeaks of an aristocratic nature of both the genealogy and ideology permeating the Chronicles. Such an impression is further strengthened by the statement that Vytenis is elected Grand Duke of Lithuania by the nobility and the fact that so much attention is given to elevate the genuine and alleged merits of the Goštautai, their relatives and allies.

In the Middle and Bychowiec redactions of the Chronicles, the history of the state is described following the traditional European model of a national chronicle.

This is further testified by the sources used, such as the Western “Chronicle of the World” and particularly “The Polish Chronicle” by Maciej Miechowita; on the other hand, the sources of the old Russians and the clichés of the Cyrillic writing side by side with the western topics disclose a syncretic nature of this history. The preponderance of the western elements, though, is undoubted.

The Lithuanian Chronicles were widespread and widely read. They were disseminated via transcripts, stored in the library of Sigismund the Old in Vilnius and the libraries of the elite representatives (Dukes Sluckiai, Odincevičiai, Zaslavskiai, Aleksandras Chodkevičius). By the late 16th – 18th centuries, representatives of lesser nobility had also acquired such transcripts as their possession. Lithuanian Chronicles laid the foundation to develop the tradition of historiography of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. They served as the basis and further development of the ideas embedded in them by Maciej Stryjkowski, Augustinus Rotundus, Albert Wijuk-Kojałowicz. The themes and motives of the Chronicles were later used by the poets and genealogists of the Radziwiłł court, the authors of eulogies and Jesuit school dramas as well as by Lithuanian historians and writers creating during the Age of Romanticism.

Literature: Lietuvos metraštis. Bychovco kronika, Vilnius, 1971

Kęstutis Gudmantas