The Guest (Merchant) House in Vilnius

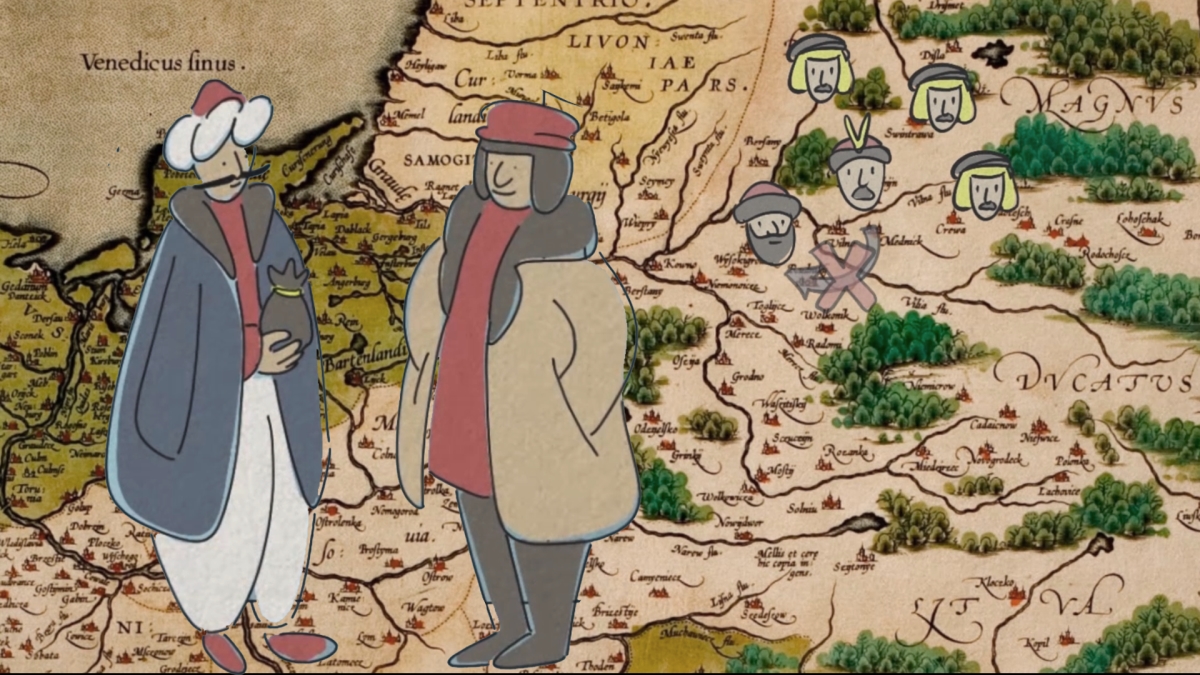

Vilnius was a vibrant trade centre in Eastern Europe in the mid 15th century. Merchants from various countries flowed into the city, and Vilnius residents were active in a wide circumference (Antwerpen-Tallinn-Moscow-Istanbul). Due to growing competition with the merchants of neighbouring countries, which became fiercer after trade between merchants was banned in Gdansk in 1442, restrictions were also put in place for visiting merchants in Vilnius in the middle of the 15th century. This ban appeared in the 1460s. By 1468 a law formed whereby Vilnius residents mediated between visitors. This was legalized by a privilege of Alexander Jagiellon on 10 March, 1505 (which has survived) for the inhabitants of Vilnius concerning the building of a guest house as well as the privilege of Sigismund the Old on 14 July, 1511 concerning the banning of trade among foreign merchants. In this way Vilnius gained oversight over the trade of prominent merchants from other countries, and a tool for implementing a mediating position among them. They first and foremost were concerned with buying the valuable furs from Eastern merchants and transport them further to the West and sell them without the help of Western merchants.

Do You Know?

A guest house for foreign merchants was built on the right side of Didžioji Street when you go from the Town Halll toward the Gate of Dawn in the autumn of 1536 in Vilnius. There were merchants that stayed there from Turkey, Wallachia, Greece and Poland. There was an extremely large amount of Muscovite merchants that came. This seems to be the reason why it may have been called the “House of the Muscovites” in the second half of the 16th century.

Customs office with accommodation

We can see from the privilege of 1505 that the initiators of the building’s construction were Vilnius residents. They complained to their ruler that merchants from Moscow, Navahrudak, Pskov, Tver and other lands were coming with their wares, doing business where they wanted and with whom they wanted without announcing to anyone about their arrival and departure. In wanting to give weight to this request, the city inhabitants showed that there could be spies among these unmonitored merchants, which is why it was necessary to build a guest house for them. Alexander I gave them permission for this and set a procedure for the arrival of guests. The merchants that came to Vilnius from the above-mentioned lands had to present themselves to a functionary of the Vilnius voivode and, upon paying a certain fee, could only stay at the merchants’ house. In this way they attempted to decide upon the question of the supervision of the guests’ trade and not allow them to sell without the participation of Vilnius inhabitants, collect customs in a quick and orderly fashion and receive income for accommodation and the services of storing their wares.

The location for building the guest house that was chosen was within the city, on the right-hand side of Didžioji Street going from the Town Hall Square toward the Gate of Dawn. It was in this place that was the beginning of the trade road to Moscow. Based on a document from 1507, historian Zigmantas Kiaupa showed that the city council began to buy plots of land for the construction of guest houses. The same was done by the city government in planning the construction of a house where Muscovite, Tatar and other foreign envoys could stay along the River Neris in Šnipiškės (as they were banned from living in the homes of the city inhabitants) together with a tavern, where mead and beer would be sold. In 1534-1536 the city bought plots of lands on both sides of the river for 330 shocks of groats. The merchants’ house was built in Vilnius in the fall of 1536. This is mentioned on a document of Sigismund the Old from September 9th, 1536. Space was left for the further expansion of the complex, and the construction of other buildings (this is showed by the 1576 atlas of Georg Braun and Franz Hogenberg).

It was indicated in the document of ruler Sigismund the Old that the merchants’ house could accommodate “foreign merchants according to the privilege of our brother King Alexander: Turks, Wallachians, and Muscovites.” As mid-16th century sources show, alongside the above-mentioned nations, this house also housed Armenians, for example, a merchant named Dadiur, Greeks (a Greek named Konstantin came in 1560), merchants from the eastern lands of Poland (a man named Stas from Kamyanets-Podilsky) as well as others. There was a particularly large number of Muscovite merchants that came. This is why, it seems, that it may still have been named the “House of the Muscovites” in the second half of the 16th century. It carried the name “Das Moskiwiten hoff” on Georg Braun’s Vilnius map from 1576. In the description to the atlas, it is indicated that there was “a famous Ruthenian hall (“Rutenorum aula”)” in the city “where merchants laid out their wares brought from Moscow, for example the most wonderful furs of wolves, foxes, martens, sables, stoats, leopards and other creatures.”

The coexistence and conflict of a colourful society

It wasn’t only foreign merchants from the East that stayed in the merchants’ house. Data has been found in sources concerning the accommodation of merchants from eastern lands of the GDL. In 1559, Vilnius burgomaster Pawel Petrowich Mnich did not allow Polotsk merchant Sidor Jesipowicz to leave the merchants’ house he was staying in for five weeks, interfered in the litigation in the court, which is why the merchant incurred great losses. In 1560, a conflict arose in a guest house between Brest Jew Moshke Konbarishkin and Muscovite merchant Stefan Filipov, whose arm was injured by Konbarishkin. Merchants from the eastern lands of the GDL still stayed there at the beginning of the 18th century. Though the guest houses belonged to the city, and the arriving merchants paid a tax to the town hall, all disputes among those who were visiting were decided upon in Vilnius’ Castle Court according to the law at the time. In addition, they also paid an arrival tax to the voivode’s castellan.

It seems that Western merchants, despite the bans placed on them to do business in Vilnius, not only continued to stay in the local merchants’ house, and not in the guest houses. According to historian Zigmantas Kiaupa, it was in this way that the merchants of Vilnius attempted to preserve their role as mediators in the trade flows between the East and West.

The guest house founded in the early 16th century operated until the end of the existence of the Commonwealth, however with the decline in transit trade (first and foremost of furs) in the second half of the 17th century and 18th century, the house was used more and more for other purposes, for example, the city courts operated there for a time.

The period of prosperity for the house lasted until about the beginning of the 17th century.

From the mid 17th century the guest house was rented out. The landlords allowed inhabitants to live in separate parts of the building complex on a permanent basis. Merchants continued to stay at the guest house, however not in such great numbers as earlier. The appearance of the building changed. Two side buildings with arched galleries were built on in the mid 17th century. The building’s inventory from 1701 has survived, which is examined by Kiaupa. At the time, the merchants’ house was dilapidated. All the structures were laid out alongside two two-storey manor house structures. The entrance to the spaces for trade as well as the storage facilities was on the first floor through the archways, while the second storey was partly for commerce and partly for accommodation. The cellars of the structures were also used as storage space. Scales stood near the gates. A tavern, kitchen and other rooms were created next to these spaces, thus this complex could accommodate up to twenty or so merchants at one time. The building took on a u-shaped layout in the mid 18th century.

Literature: З. Кяупа, Гостинный двор в Вильнюсе, Наш радавод, Гродно, 1991, вып. 3, с. 449–455.

Aivas Ragauskas