The first money: silver alloys and their forgery

Scales are often discovered in the graves of the Curonians, the coastal dwellers. Those graves date back to the end of the 10th–12th centuries. Iron weights plated with copper are discovered next to the scales. Fragments of the scales and weights are known from the 14th century cultural layers of the Lower Castle of Vilnius and Kernavė. Archaeologists usually call the graves of rich men in which scales are found the graves of merchants they are a new social category in the lands of the Balts. It is unlikely that those scales were used to weigh salt or any other commodity. Most probably it was then that due to the Scandinavian Vikings silver was started to be treated not only as raw material for elaborate jewellery but also as a means of accounting-trade transactions, which had a fixed price of a certain weight equivalent. The said weights are different however, they have marks at the ends, most often little eyes. The unit of weight of the majority of the weights discovered in Lithuania equalled to 4–5 or 8–10 grams. The unit of weight is obtained by dividing the weight of the weight by the number of eyes cut on it. It is thought that such a unit of weight was dictated by the silver coins – Dirhams, which weighed 4 grams, and were brought from the Arab countries en mass in the times of the Vikings. Minted silver alloys of rectangular cross-section, of different weights, sometimes resembling a spiral bracelet characteristic of the Scandinavian Vikings spread in the lands of the Balts several centuries before the state was created. They circulated as a means of payment divided into a certain weight depending on the need.

Do You Know?

The Lithuanian “long” are silver alloys, which have the shape of a half-round stick, 13 cm long and, most of them weigh 100–110 grams. The beginning of making these alloys is related to the period of the rule of Mindaugas. One could buy up to 15 sheep for one alloy, and a horse could be bought for one and a half alloy.

Smaller denomination cut by an axe

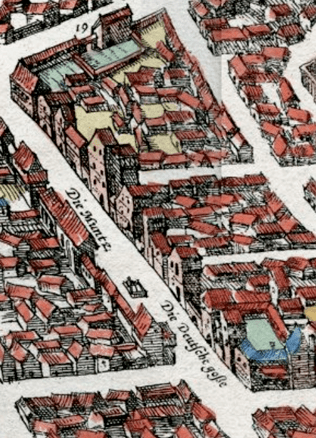

Another step had to be the introduction of local monetary systems related to foreign units of weight. This could be implemented only after a centralised political and economic structure that had the power of the dictate – the state – had appeared. Therefore, it is unclear why many historians and numismatists move the appearance of the oldest local money – the Lithuanian “long” as far back as the beginning of the 12th century. It would be more reasonable to relate the beginning of making these alloys to the period of the rule of Mindaugas (around 1236–1263).

The Lithuanian “long” are silver alloys that have the shape of a half-round stick, are 13 cm long and most of them weigh 100–110 g. The weight of the Scandinavian Mark of that time was 204 grams. Most probably the Lithuanian monetary alloys were half weight of that Mark. Today more than 50 sites of the discovery of the Lithuanian “long” are known, their largest part is in the territory of Lithuania, however, the geography of the locations covers all the lands that belonged to the Grand Duchy of Lithuania at that time. The greatest number of them was discovered in the treasure trove of Vilnius (Rybiškiai) – over 530 units, a total of 60 kg of silver.

One could buy up to 15 sheep for one alloy, and a horse could be bought for one and a half alloy. However, what did the person who wanted to buy only one sheep do? According to the researchers, it was only the ruling elite who needed the Lithuanian “long” to settle different, most often large international accounts. This idea was determined by the fact that earlier the Lithuanian “long” were found only accidentally, in the treasures and most often they were whole, unbroken. The majority of the Lithuanian “long” have from 1 to 18 deep notches, one can notice incisions made by a knife on its inner side. It was thought that these notches signified the hallmark of the alloys or appeared when the quality of silver was checked by means of a hack. Archaeological investigations of the past several years in the town of Kernavė of the 13th–14th century corrected these statements. A total of 17 fragments, most probably of the lost Lithuanian “long”, were discovered in the homesteads of the ordinary town dwellers-craftsmen. Their weight ranged from larger ones weighing 6,8 g to the pieces hardly weighing 0,45 grams. Notches were used seeking to break off a missing part of the “long.” A small fragment of the alloy was cut crosswise to make still smaller payments.

The Lithuanian “long” were used not only when settling international accounts or buying a herd of sheep but also when carrying out smaller transactions.

A treasure of four whole Lithuanian “long” has been discovered in the homestead of a craftsman in Kernavė. It is thought that it was hidden at the time of the Crusader attack in 1365. Hence, an elite member of the community had a large “amount” of the Lithuanian “long” at his disposal.

Alchemy of swindlers: how to make silver from copper

It was thought that the Lithuanian “long” contained 85–95% of silver. These data were obtained having carried out a chemical examination of seven Lithuanian “long” stored in the Lithuanian National Museum. Different results, however, were obtained after the composition of silver alloys of Kernavė had been examined. The quantity of silver in four alloys discovered in the above-mentioned treasure was only 49.87; 60.89; 76.25 and 82.49%. Only in seven out of seventeen fragments of the silver alloys the hallmark exceeded 85%. In another seven alloys the quantity of silver accounted for from 39.06 to 78.72%. In three fragments of the Lithuanian “long” no silver was found at all. Two alloys were made of cast copper and most probably it was only silver plated, and one was made of tin. Perhaps the multiple notches made by a knife were made when checking whether the alloy had not been a counterfeit. By the way, six fragments of the alloys having the shape of a half-round stick were also discovered in the territory of the Lower Castle of Vilnius; one of them was a tin counterfeit. The dead could also “enjoy” the counterfeits in the world of the dead. Three fragments of the alloy of the form of a half-round stick, with one of them being a counterfeit made of tin and copper alloy with admixtures of lead, were discovered in an old burial ground in Verkiai (the city of Vilnius). Monetary alloys were discovered in the grave of a rich man dating back to the 14th century, in a leather bag together with a fire steel and a razor. Hence, it seems likely that forging the Lithuanian “long” in the second half of the 14th century acquired a mass character. Technologically this is not a complicated process; alloys were simply cast in one-sided open moulds.

Thus, a person who knew the trade of jewellery could make “the Lithuanian long” of different chemical compositions.

At the end of the 14th century the monetary reform was implemented. Larger, up to 185.7 grams in weight alloys of a triangular cross-section, referred to as trilateral in literature were started to be cast. It is thought that the new alloys were related to the Grosz of Prague whose 50 units weighed 189 grams. Approximately at the same time the first Lithuanian minted coins were started to be forged, however, trilateral alloys remained in circulation until the end of the 15th century. Having conducted investigations into four trilateral alloys from three different locations in Eastern Lithuania, it was established that their hallmark ranged within the limits of 97.05–98.9% only. Perhaps one of the reasons of putting monetary silver alloys of new type into circulation was manufacture of the Lithuanian “long” that “escaped” the state control, and their massive counterfeiting. Meanwhile trilateral alloys suited perfectly to making large, perhaps even international payments and functioned alongside the minted coins used in everyday trade.

Gintautas Vėlius