Lithuanian merchants

The first merchants of Lithuania equated to “simpletons and dogs”

The first data about the merchants in Lithuania provided in the written historical sources revealed that in most cases they were arrivals from other countries, the Germans or other foreigners rather than Lithuanians. Lithuanian merchants of the most distant past were members of Lithuanian soldiery or their escort who became sellers of the seized booty in larger trade cities of Russia. The Lithuanian merchants who raise no doubts and who did not exist at all in the trade privilege to the dwellers of Riga that was not approved by Mindaugas in 1253, were mentioned for the first time in a specific social environment – among the serfs of the Lithuanian nobility. Duke Treniota’s hired labourers familia were robbed by the Livonian brothers in the land of pagans (Samogitia?) during the time of the rule of Mindaugas. Goods belonging to Treniota were seized from them. In the second half of the 13th century people of Duke Traidenis who were similar to the former were detained in Riga. The Ruler referred to them as “simpletons and dogs” – he did not care about their fate.

The first Lithuanian merchants were agents of the nobility who were unable to act for themselves and who were not free.

The role of the Grand Duke and the nobility in their emancipation is exceptional.

Do You Know?

It is natural to read the names of the Lithuanian merchants with a reference to their origin (place) at the beginning of the list of the Book of Debts of Riga (1285–1352). They are from an important centre of governance of Lithuania – Kernavė: Rameikis Rameyze (1290) and Studilas Studile (1303), both were merchants of wax.

More Lithuanian merchants were mentioned in the Book of Debts of Riga. They were active trade partners to the dwellers of Riga and were reliable suppliers of wax and fur. They bought goods on credit but always paid back the debts. Some of them had accumulated large capital and were able to credit commercial operations. In old historiography almost every Baltic name of a merchant that was in the Book of Debts of Riga was attributed to a Lithuanian merchant and the number Lithuanian merchants totalled about 30 in the Book. But the latest historiography does not contain many of such names – just a few. It might be that a part of the merchants simply were not put on the debtors’ list.

Rudiments of free merchant estate

Lietuviu pirkliu gurguole. U. Richentalio kronika. XV a.

According to Edvardas Gudavičius, the Lithuanian merchant who was not personally dependent on the Ruler, and who “dug a grave for the Duke’s functionaries” appeared gradually. It is necessary to look for those people not among the “simpletons and dogs” of Traidenis, but among those Lithuanians who traded in Riga and who were detained by the dwellers of Riga in the times of Grand Duke Traidenis demanding that the Ruler of Lithuania should compensate for the losses incurred. According to the data of the 14th century, such merchants were still people dependent on the nobility. Therefore gradually, changing their social status, the Lithuanian merchants grew stronger. If the 1323 Vilnius Agreement concluded between Lithuania and the Order spoke only in a general way about the Lithuanian and Livonian merchants “on both sides,” the Peace and Trade Agreement of 1 November 1338, on the basis of the trade rights and their security guarantees available, put the Lithuanian merchants in one line with the German (residing in Riga) and Russian merchants. Therefore, from the first half of the 14th century one as though could speak about the Lithuanian merchant who was not free and belonged to the families of the noblemen. However, Grand Duke Gediminas, his sons and all his noblemen boyarlen were the first among the Lithuanian rulers to promise guarantees of safe trade provided for in the said Agreement. It was they who still had their trading clients or confidential agents, that is, merchants. Merchants further remained related to the ruling dynasty and its noblemen therefore they are to be regarded as an estate of the society that was unable to act for itself. During the time of the rule of Gediminas this estate grew stronger and its growth was determined by the needs of the estate of the Ruler’s nobility, which was being formed at that time, as well as by a favourable commercial and political conjuncture near the Daugava River.

XII a. pab. – XIII a. vid. pirklių svarelis.

Svoris: 145,98 g.

Diametras: 63,7 mm.

Merchant “quarters”

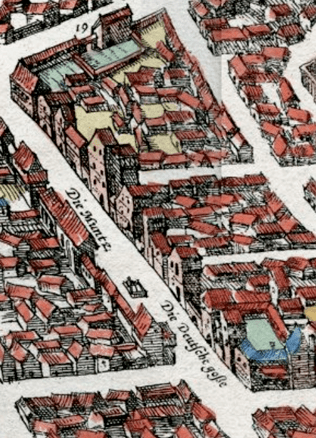

Russian merchants of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania mentioned in the 1338 Agreement resided in the towns of Polotsk and Vitebsk, which had approved the Agreement, whereas the Lithuanian merchants who were taken under the wing of the dynasty and the nobility, first of all can be found in the courtyards of the Grand Duke and the settlements of the castle, as well as close to the castle. Archaeological excavation in Kernavė confirm that in the second half of the 13th–14th centuries the merchants concentrated close to the castle, on the Castle Hill and in the lower “town” where Orthodox Christians lived. Attributes of trade (a coin – Lübeck bracteate, a fragment of scales of Riga model, a merchant’s grave, the implied place of trade) prove that a local merchant appeared in significant political and administrative centres of the ruling dynasty, the “Russian town” in Vilnius as an open settlement of Vilnius, appeared at the turn of the 13th-14th centuries together with the German colony on the western foot of Gediminas Hill (later the Palace of the Lower Castle was built there). Only the suburb inhabited by Orthodox craftsmen and merchants originated at the ford over the Vilnia River where the eastern and southern routes intersected. The localisation of the German colony changed at that time. In the second half of the 14th century it is supposed to have been in the area of the current German Street in Vilnius, especially in the surroundings of the Church of St. Nicholas. “Trade” infrastructure allows this conclusion to be draw: in other countries the Church of St. Nicholas, which is the patron of merchants, traditionally served as a warehouse of good, the Church of the Holy Virgin Mary with a monastery, the name of German Street. All that are traces of the German colony of merchants and craftsmen.

Šv. Mikalojaus, pirklių globėjo, bažnyčia.

1893 m. J. Kamarauskas

The rudiment of the new Lithuanian social layer – merchants – in the second half of the 14th century was still weak and politically non-influential as compared with the Germans of Riga in Vilnius. They operated in Vilnius from the times of Grand Duke Vytenis, the Franciscans were responsible for their pastoral counselling. Hanul, the Senior of the Livonian merchants (Germans) in Vilnius, actively supported the actions of the young Grand Duke Jagiełło in establishing himself on the throne in Lithuania and becoming the King of Poland.