Customs officer Heinrich Sliacher: a German under the sign of Matthew the Apostle

To be a customs officer in the Christian world meant to expose one’s immortal soul to ruinous temptations. The name of a customs officer or a collector of taxes in the New Testament was synonymous to a sinner or a pagan. But even in the Holy Scriptures one could find something to justify this profession: Jesus himself sat down at the table together with tax collectors, and Matthew, the Apostle and Evangelist currently referred to as the patron of bankers, accountants, and tax collectors, was himself a tax collector.

Customs duties in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania were collected as far back as the 14th century. However, there are no data available about tax collectors. In the sources of the 15th century customs officers were often mentioned but all of them were “small fish”, most often they were Jews, and little is known about their personalities. It was German Heinrich Sliacher who took over an especially profitable Kaunas Customs of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania in 1496 and became an exceptional customs officer. That personally played a significant role in the history of Lithuanian economy.

Advantages and disadvantages of trade with the ruler

Do You Know?

The German merchant Heinrich Sliacher regarded to be the first person to have minted the Lithuanian coins laid the foundations for the monetary system of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. In 1495 he became Chief of the mint opened in Vilnius.

Heinrich Sliacher is thought to have come from Reutlingen (currently Baden-Württemberg land in Germany), which belonged at that time to the Swabian League (Schwäbischer Bund). In the 14th-15th centuries German towns acted as intermediaries for Venetian merchants who carried luxury goods from the Near East. Perhaps through the trade networks of the town Heinrich Sliacher came to Krakow and became a citizen of that town in 1479. He engaged in trade and financial operations there, which sometimes opened the way to the King’s court. Though Heinrich Sliacher’s interests reached the Grand Duchy of Lithuania where he is mentioned during the last years of Casimir Jagiellon’s reign. He engaged in usual activities there. The entry in the account book of the Grand Duke Alexander in 1499 runs as follows: “The Duke owes Heinrich Sliacher for damasks, velvets, fabrics, for saffron, pepper and other spices used in the kitchen and for the debts of the courtiers warranted to him and certain amounts of money… All in all, the amount totals three thousand two hundred and sixty-four scores.” Hence, Heinrich Sliacher provided the court with luxury goods, kindly granted credits to the Ruler and the courtiers whose paying capacity was confirmed by the Ruler. He was a privileged merchant, carried wholesale trade with the help of pen and paper rather than with scales and weights. Closeness to the Ruler liberated Heinrich Sliacher’s trade from bureaucratic obstacles but at the same time “presented’ him with the court’s bills that remained unpaid for a long time. Seeking to compensate for the losses it was necessary to find additional sources of income, which would provide working capital.

Customs control guaranteed uninterrupted flow of cash therefore it was a dream of all large merchants.

Heinrich Sliacher managed to make this dream come true. In the middle of 1495, Grand Duke Alexander banished the Jews out of Lithuania. It seems that making use of the anti-Semitic wave that swept though Europe at that time the Ruler of Lithuania got rid of his old creditors in this way. It is difficult to say whether he was made to behave like that by Christian creditors too, but the latter found the expulsion of the Jews useful.

Heinrich Sliacher was not ordinary: he did not set his heart on the usual redemption of customs duties (in those days called arenda) but on the control of the whole emission of money of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. Relations in the court and personal qualities helped Heinrich Sliacher to become Chief of the mint in Vilnius around 1495. Before that time Vilnius mint did not operate. Its opening was a novelty; it was at that time that the foundations for the monetary system that became established in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania were laid. Therefore, Heinrich Sliacher is sometimes regarded as the first persons to have minted the Lithuanian coins. After that, when in 1501 Alexander Jagiellon became King of Poland, Heinrich Sliacher was appointed Chief of the mint of Krakow.

Financial interests overshadow the national ones

It was impossible for one man to carry out such a wide range of activities (take care of trade, crediting of the court, supervision of the customs and the mint). Heinrich Sliacher was sometimes represented by his servant Iržik (most probably a Czech) in the court of Alexander Jagiellon. The relations between these two people testifies to Heinrich Sliacher’s possible activity in the market of Bohemia, which was thriving at that time. Ulrich Hozij, from Pforzheim in South Germany, and Henryk Karlovich (perhaps from Bohemia?) were Heinrich Sliacher’s closest people. They were Heinrich Sliacher’s business partners. The former married the widow of Heinrich Sliacher’s brother and at one time headed the mint of Krakow, and the latter married a sister of the widow of Heinrich Sliacher’s brother and in 1498 bought back the customs duties of Brest from the Ruler. These relations show that Heinrich Sliacher always belonged to the networks of the merchants of Central Europe (South Germany). This explains his disagreements with the Hansa merchants of northern Germany. At the beginning of 1495, the merchants of Revel (Tallinn) were happy with Heinrich Sliacher’s position in Vilnius; they did not communicate with him before that. Most probably they knew or felt that the ruler of Lithuania was going to get rid of the Jewish creditors.

Heinrich Sliacher’s position aroused hope that wide possibilities would be open in the market of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania to the merchants of the German nation.

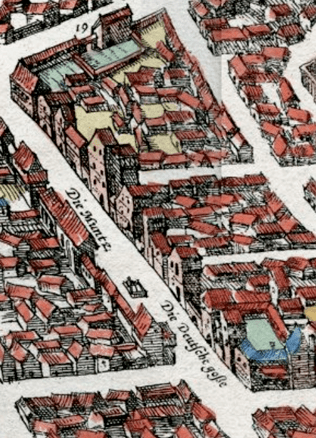

However, the history of supporting German merchants was quite different. Heinrich Sliacher went on to buy back Kaunas customs from March 1496 to March 1499 at 1 350 scores grosz. Most probably, at the beginning of that period he acquired a house in Kaunas so that he could at least sometimes control the activities of the customs when he arrived. There he encountered a long-lasting friction between the local merchants and the merchants of Gdansk (the Hansa city). The merchants of Kaunas tried in all possible ways to restrict the rights of the merchants of Gdansk to carry goods to Vilnius where the scopes of consumption were larger. Heinrich Sliacher who had his own business in Vilnius, did not want to have a competition with Gdansk merchants. When he began administrating the customs the merchants of Gdansk started writing complaints. They were angry because they had to pay taxes for the second time on the goods carried from Kaunas up the country. It might be that Heinrich Sliacher even falsified the documents presenting the second customs duty as having existed for a long time. The rulers of Lithuania were unable to resolve these problems for many years therefore the activities of Hansa office got stuck, and in 1540 it stopped altogether. This was how Heinrich Sliacher “served’ the glory of the merchants of the German nation.

In 1504 Heinrich Sliacher lost his post as a chief of the mint in Krakow but as compensation was appointed to head the customs of Kaunas till 1507. In 1504, he arrived in Lithuania and died. He had no children therefore Heinrich Sliacher’s property and supervision of Kaunas customs were given over to the executors of his will Ulrich Hozij and Henryk Karlovich.

Literature: Karalius L., Kauno muitininkas Heinrikas Sliacheris (1496–1499; 1504), Kauno istorijos metraštis, t. 3, 2002, p. 185–201.

Eugenijus Saviščevas