Entertainers at Vytautas’ Court: Musicians, Dwarfs and Jesters

Passion for collecting was stronger than the interstate conflicts

Vytautas, the Grand Duke of Lithuania, returned to Lithuania from the German Order in 1392 bringing together a taste for a number of things he got used during the five years there. That was the period when he took part in raids against Lithuania with the Order’s troops and administered the castles under his supervision. In addition to that, he had a number of chances to meet nobles from Western Europe many of whom would still visit Prussia at that time. The visitors included the Earl of Derby, the future King Henry IV of England, who arrived there with a large escort in 1390. It was that year that the English aristocrat added two Lithuanians to the collection of exotic dwellers of his court during the raid against Vilnius he took part in together with Vytautas. He paid one mark for the two men, according to the inscription in his book of travel expenses, the deal that the book lists beside the purchases of wax and nuts.

In European courts of the late Middle Ages, “pagan Lithuanians” were most probably treated just like people from other remote lands, such as Arabs or Africans.

Presumably, it was around that time that Vytautas developed his taste for the colourful courtly life with musicians, dwarfs, jesters and other “exotics” – the taste that would remain with him to the end of his days.

That was a marginal and mobile group of the courtly community; Grand Dukes would often lend them or give them as presents. The Grand Master of the German Order would eagerly exchange them with Vytautas because, despite the long-lasting conflict, they both belonged to the same world of nobles and shared similar way of life. In his letters to the Grand Master, Vytautas discussed features and jokes of his dwarfs and jesters in detail. Paul von Rusdorf, one of the Grand Masters, wrote Vytautas in 1421, shortly before the latter invaded the Order’s territory together with the Polish troops: “Your magnificence wrote us about the dwarf, who is quite old now, a Russian and does not speak Lithuanian; who, if we liked, you would send us with pleasure. Dear Sir! As far as we have found out, a cleanly and honest dwarf lives with you, who can ride a horse at the moment; we do not know whether You meant that one or any other. However, whatever man Your Majesty sends us, we will receive him with respect and gratitude.” Vytautas responded to that appeal of the Grand Master who thanked Vytautas several months later for two dwarfs who had reached his court in Marienburg “fresh and on time.”

Hene, the jester, “knighted” with a club

The court jester enjoyed a specific status among other “entertainers”, because he balanced between official ceremonials of the court and its marginals.

Jesters became common in the courts of European rulers in the 14th century. Soon the fashion of having them reached the court of the Grand Masters. Vytautas most probably followed the example of the German Order when he chose the “official” jester for his court. Historical sources have preserved his name for us – Pischer. But it is the other jester of the time that the sources write much more about.

While preparing for a far-off expedition to the lands of Rus’, in 1427, Vytautas sent a special request to the Grand Master of the German Order asking him to permit his jester, Hene, who had earlier visited Vytautas’ court a number of times, to take part in the raid. In the beginning of the raid, Hene made a joke that pleased the Grand Duke so much that he wrote a letter to the Grand Master about that episode only: “Vouchsafe to know that Hene the knight caught us up in Krėva at the time of the raid which we had written you about, and we are grateful for sending him to us. But he arrived dressed as a knight ready for a foray (hoffertig), hence he wishes to look witty and smart, because we have knighted him, and he no longer wishes to be a jester or a joke maker. He tried to persuade us that once we have knighted him, we should no longer treat him as a jester. Then he threw away his jester clothes in disobedience after which we threatened him with a miss club [Vytautas was already old and ill – R. P.] /…/ [He finally decided] to be a knight in the mornings, smart and decent, and to perform jester’s duties in the evenings.” During that same raid, Vytautas ordered “to sew him another jester clothing featuring ears, pockets etc…” Therefore, turning the knightly ceremonial into a parody, Hene treated Vytautas’ club hit as a knightly stroke and asked for a proper respect. Hene was a clever jester. In addition to making jokes before Vytautas and his friends, he also wrote letters to the Grand Master to inform him about the raid.

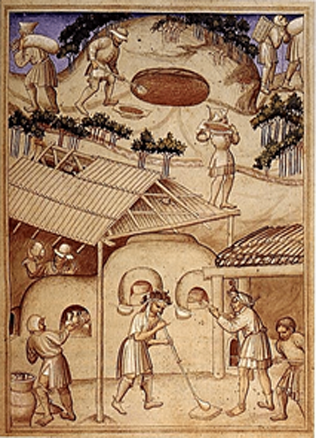

Music was an important part of the courtly culture of entertainment. Musicians used to travel from one court to another. Vytautas, Jogaila and Švitrigaila used to send several categories of their musicians, including trumpeters and pipers, to the court of the Grand Master. In 1406, the Grand Master sent to Vytautas’ court the entire chapel led by one Pasternak to play at the celebration. In 1393, Jogaila sent Vytautas his trumpeter, Heinze. Musicians would entertain the Grand Duke as well as his escorts and guests during feasts; they would also take part in other ceremonial rituals within the court. One such example is trumpeters welcoming honourable guests.

Prestige of the mediaeval court

The colourfulness and solemnity of the courtly life reflects partly the individual inclinations of the ruler and, at the same time, testifies his efforts to adhere to the European requirements and standards of the court of the sovereign ruler.

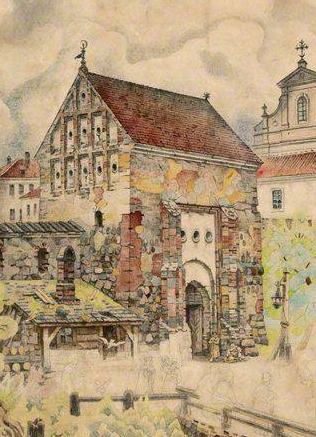

That is why nobles from Europe would discover traditional forms of courtly and knightly culture within Vytautas’ court as well as standard structures and personalities, including residential castles, feasts, receptions, raids, heralds and jesters. During Vytautas’ reign, we observe the changes in the residential ruling with new or reconstructed castles, such as those in Trakai, Vilnius, Grodno, Kaunas, and Lutsk, gaining more importance in daily life. It was there that Vytautas used to spend a big part of his time and it was they that helped him to increase the number of his courtly residents. The castles served him as public scenes to demonstrate power and prestige through pompous welcomes of envoys and other guests, rituals of clothing exchange, knighting ceremonies, convivial and exotic objects and people. The symbolic part of the residential reign enabled the Grand Duke to underline the exclusiveness of his monarch status among other Lithuanian nobles and to convey the message about the sovereign Duke to the outside world.

Literature.: Rimvydas Petrauskas, Vytauto dvaras: struktūra ir kasdienybė, in: Naujasis Židinys–Aidai, nr. 1–2, 2003, p. 39–44.

Rimvydas Petrauskas