Baroque fireworks: fire dramas with political content

In Europe firework displays have been held on various occasions for several hundred years, their purpose being to fascinate and amaze the onlookers. In the 15th century, fireworks became a part of secular entertainment, but they gained exceptional significance during the Baroque.

In the 17th century fireworks became an integral part of the court festivities, usually serving as their culmination. The “artificial fires”, which mimic thunder and flashes of lightning, created the impression of heavenly powers. During the Baroque, light became an important element of commemorative decoration, used to enhance the effect of theatricality. On the other hand, light is an archaic symbol of divinity, so the fireworks were perfect for creating the impression of grandeur and splendour – and that is exactly what the magnates were after.

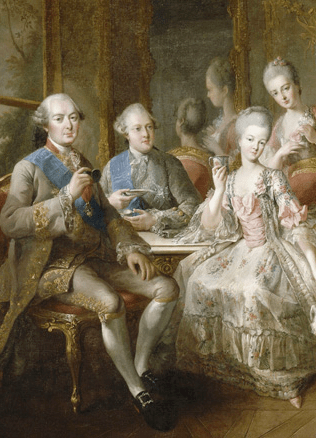

In 18th century Europe, firework displays became more than a part of court entertainment and turned into huge public spectacles fascinating people of all walks of life.

A task for a military engineer in times of peace

Contemporary firework displays usually are checkered flashes of light in the sky. The Baroque firework displays were different, they resembled a theatrical performance and developed as an allegorical narrative. They often depicted a drama, the conflict between good and evil, culminating in the victory of the former. Over time, the allegorical content of fireworks grew increasingly complex and difficult to understand. Therefore, in the 17th century special prints clarified the meaning of “firework dramas” to European audiences.

“

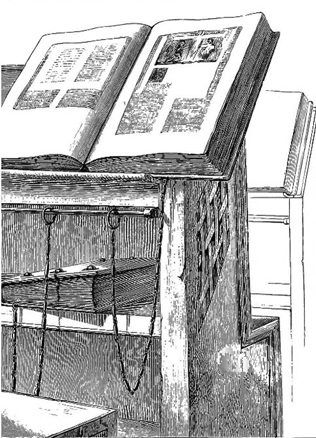

This art was laid out in artillery textbooks, such as “The Great Art of Artillery” by Kazimierz Siemienowicz, a military engineer from the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. The book, first published in 1650, would become the most important European textbook on artillery for the next two centuries.

The fireworks were designed by military engineers. Production of “artificial fires” was an expensive and time-consuming job. Usually, it took several weeks for engineers to design the elaborate facilities for celebrations, in which they were aided by architects and sculptors. The fundamentals of arranging firework displays had become a part of an engineering education.

This art was laid out in artillery textbooks, such as “The Great Art of Artillery” by Kazimierz Siemienowicz, a military engineer from the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. The book, first published in 1650, would become the most important European textbook on artillery for the next two centuries.

It includes a whole chapter dedicated to firework displays. The author names four reasons appropriate for fireworks. The list starts with the coronation of a ruler, the ingress of the highest ecclesiastical or secular official, and ceremonies in their honour. Other proper occasions include military victories, wedding parties, and balls for friends.

Theatre of lights in the sky

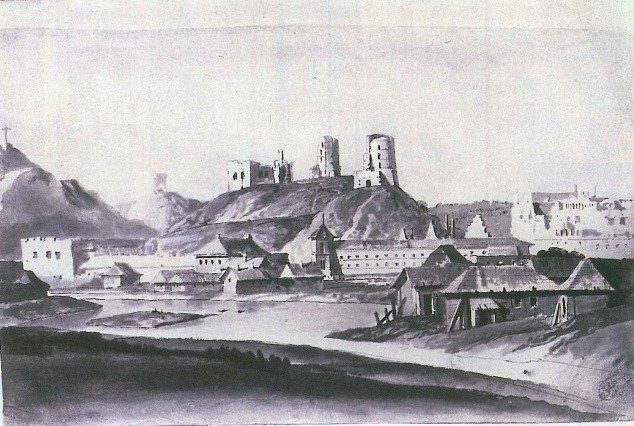

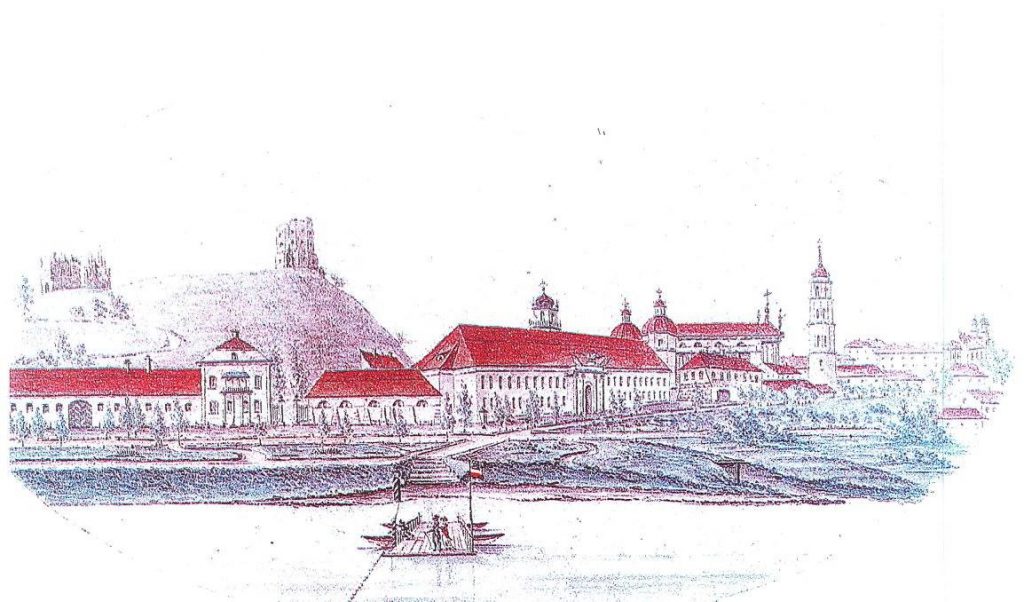

Baroque firework displays lasted for up to four hours. They consisted of several acts, just like a dramatic performance, with different figures lighting up in every act. Fireworks were often displayed by the river, as reflection of the fires in its waters enhanced the effect and “created the visibility of another starry sky.” In Vilnius, fireworks were organized on both banks of Neris, most often by the Arsenal, and sometimes right above the river.

“

As firework displays were intended to to represent the powerful, among the among the plethora of figures appearing during the spectacle dominated symbols of power. For instance, the royal crown, sword and sceptre, occasionally, the allegorical representation of the ideals of the state – justice, freedom, and glory.

Viewers especially appreciated the ingenuity of firework design. The descriptions of firework displays in contemporary newspapers feature all kinds of praise, calling them “A wonderful spectacle, in the common opinion, not yet seen before.” The abundance of “artificial fires” and the effect they create, imitating the powers of nature, was also important. The authors emphasized that during the fireworks “the sky became as bright as at noon” or “there was so much fire that it looked as if the river was in flames.” The grandeur, almost equal to that of the elements, was enhanced by the figures representing celestial bodies.

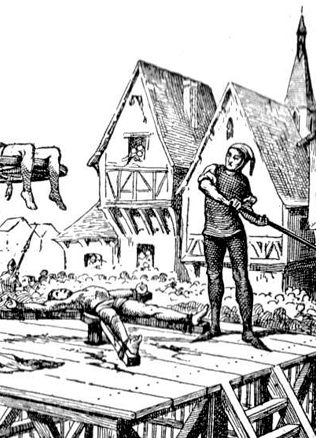

Firework displays included mythological creatures, such as mermaids floating down the river or fire-spitting dragons. Siemienowicz presents a project of such figure in his textbook as well.

As firework displays were intended to to represent the powerful, among the among the plethora of figures appearing during the spectacle dominated symbols of power. For instance, the royal crown, sword and sceptre, occasionally, the allegorical representation of the ideals of the state – justice, freedom, and glory. Images of ancient gods of was were also used, figures of Mars and Athena being the most prominent among them. The ruler was usually depicted as a knight or a warlord as to symbolically emphasize his obligations as the protector of the realm.

Flaming “press releases”

Firework displays, just like any other occasional decoration of the time, often featured a number of compulsory symbols, such as the coats of arms of the ruler or the highest dignitaries, surrounded by slogans and honorific phrases. Sometimes the use of heraldic figures was ingenious, for instance during the birthday party of Józef Sołłohub a lion, the main figure of his coat of arms, moved from the window of the Arsenal and across the River Neris and set alight the slogan, that read “Glory to Augustus III, the King of Poland”.

“

A firework display could reflect contemporary political developments. During a festival in honor of Augustus III, the magnate Michał Ksawery Sapieha used the coats of arms of the King’s allies in the Seven Years’ War in his firework display followed by inscriptions praising the just and victorious fight.

Motifs of fire and light were often interwoven in the inscriptions surrounding the coats of arms and symbols. To emphasize the peaceful reign of Augustus III, the royal coat of arms was adorned with the following text at the fireworks display in 1743: “Although the world is burning in flames of war from all sides, the stars guard Augustus with their quiet light.”

A firework display could reflect contemporary political developments. During a festival in honor of Augustus III, the magnate Michał Ksawery Sapieha used the coats of arms of the King’s allies in the Seven Years’ War in his firework display (in which Augustus III took part as the ruler of Saxony) followed by inscriptions praising the just and victorious fight. The Austrian Eagle was accompanied by the entry “I will not retreat until I have defeated,” the Russian Eagle with the slogan “The one who fought justly,” and the Swedish Crown with the words “Faith, justice, and courage”.

Large crowds enjoyed the fireworks, but their purpose was not limited to mere entertainment. The political content of such events is proven by the fact that they were dominated by the symbols of power. The printed and publicly distributed descriptions of the fireworks did not spare the praise of the organizers, revealing their intentions and the reaction of the audience.

The account of firework display in Vilnius, 1754

On August 3, the Marshal of the Supreme Tribunal of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, Konstanty Ludwik Plater, celebrated the name day of His Majesty Augustus III and on that occasion launched an expensive, wonderful, and ornate celebration. Dozens of cannon salves greeted the guests on the eve of the celebration. The next day, the Marshal hosted a dinner for 140 guests that included senators, officers, noble ladies, the entire Tribunal, clergy, and other guests.

After the dinner, at nine in the evening, fireworks displayed in a special structure were lit, surprising all who were present.

At first, people saw a triumphal gate supported by several columns. On top of them were the coats of arms of the Commonwealth and the Saxon sword. Above the sword was a golden crown, and above the coat of arms was a figure of Justice holding scales and a sword.

“

At the beginning, three rockets were fired amid the thunder of sixteen cannon; a lion, running from the Arsenal window across the River Neris towards the firework machina, ignited the letters “Vivat AUGUSTUS III. REX Poloniarum”.

At the beginning, three rockets were fired amid the thunder of sixteen cannon; a lion, running from the Arsenal window across the River Neris towards the firework machina, ignited the letters “Vivat AUGUSTUS III. REX Poloniarum”, the coat of arms of the Republic and the letters AR with a crown, and then returned. Then rockets were fired, fireballs from four cannons one after the other, fire mills and pyramids were lit up as well as various letters and other things.

In the second act, various lower figures were seen alongside balls, mills, earth fountains, and other innumerable fires.

The third act took place over the water and began with a floating flaming siren accompanied by burning swans themselves launching fires. After that, the citadel sailed, and on its pedestal stood a carved and beautifully illuminated figure of the king in armour. In the end, other fires on water were seen, of an ever-changing form and idea. The fireworks ended at midnight after the last rockets were fired accompanied by sixteen blasting cannons. Everything went on amidst uninterrupted fire.

Do You Know?

This type of art was laid out in artillery out textbooks, such as “The Great Art of Artillery” by Kazimierz Siemienowicz, a military engineer from the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. The book, first published in 1650, would become the most important European textbook on artillery for the next two centuries.

Lina Balaišytė