Bernardine Convent in Vilnius as a Classical Piece of Gothic Architecture

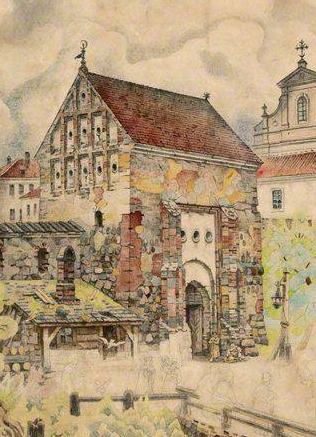

St. Franciscan Friars Minor the Observants, called the Bernardines, came to Vilnius in the mid-15th century. The Grand Duke of Lithuania Casimir Jagiellon was most kindly disposed to this active and mobile Order, popular all over Europe. Not surprisingly, he funded the construction of the Bernardine Convent and Church in the capital of the country, which started in 1469. The Vilnius Convent was to evolve into the Centre of the Bernardine Order in Lithuania, therefore the buildings of this ensemble served as a certain model and an example to be followed by other Bernardine convents constructed in the territory of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. The Vilnius Convent reflected the more general construction traditions of the Order. The first, presumably wooden, St. Bernardine’s church in Vilnius burnt down as early as the 15th century. About 1490 the Bernardine monks constructed brick foundations of the Convent. However, in 1500 a major part of the church brickwork had to be pulled down and reconstructed.

Under the sponsorship of Alexander Jagiellon, the Radziwiłł family, and other noblemen of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania as well as citizens of Vilnius, an exquisite Gothic ensemble was erected in the first decades of the 16th century. The ensemble contained the building of the Convent itself, the “major” church of St. Francis and St. Bernard, with the “minor” church of St. Ann’s, added to the ensemble in the junction of the 15th-16th centuries. St. Ann’s brotherhood was established at this church, under the care and patronage of the Bernardines. This ensemble stood out against the Vilnius panorama of the 16th century as a most memorable example of architecture. To illustrate the point, it deserved special mention in the description of the Vilnius City, published in the Atlas of the World Cities by George Braun in 1576: “The Bernardine Convent, built of burnt bricks, is most beautiful and famous for its magnificent architecture.”

The Architecture is enriched with the would-be classical innovations

The “major” church of St. Francis and St. Bernard was one of the largest in the capital of those days and one of the most beautiful in the entire Grand Duchy of Lithuania.

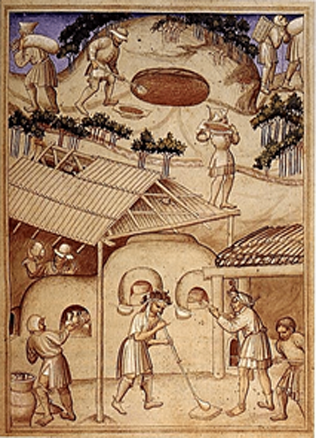

Even though it was ravaged during the fires and wars and therefore renovated by the Bernardine monks more than once, with the inevitable replacement of separate part of its brickwork ensuing, the Gothic architecture of the church has survived almost intact up to our days. It is characterised by a subtle harmony of proportions and the amazing consistency of the entire composition and its details. The builders of the Bernardine Convent used numerous architectural elements, regarded at the time as the innovations in the sphere of construction and engineering. The tower of the belfry, glimmering with the tracery of recesses, tiny niches and arkels is solemn in a reserved way and serves as an exquisite example of profiled bricks, displaying an ornament of Masswerk and Bluework, the elegant façade of the church, decorated with cuneiform arches, and many other architectural details testifying to the ingenuity of the old craftsmen have never ceased to be an object of delight for church visitors. Regrettably, the surviving upper part of the main façade of this church has been restored a few times, and inevitably the Gothic church acquired certain features characteristic of Baroque. The Church plan and size is in tune with traditions of the Bernardine brotherhood and taste of the epoch. The main part of the naves, allotted to the needs of the laity, is spacious, right-angled and high (currently, the level of the land next to the church and the level of the floor inside the church has risen, which means that the building looked even taller in the old days); it is extended by a long more narrow and lower Presbyterian part dedicated to the Bernardines and called the monk choir – the pews installed here were meant to seat the Bernardine monks during the liturgy of the Holy Mass (Lat. stalium). The monks also used to chant here the liturgy of the hours and other devotions. In the past, the boundary separating the space for the secular and religious congregation, was marked with a metal lattice, installed inside the church, next to the first pair of pillars.

The symbols hidden in the Bernardine walls

The church walls are divided by high windows having the shape of a pointed arch. In the early 16th century these windows were larger (to imagine their actual height, one has to discern the marks of the immuring cases in the lower part of the southern wall, done at a later time, and disregard the present organ balcony, which was absent in the Gothic sanctuary). The four pairs of elegant pillars support the vaults (the part of the ornate crystal and meshy Gothic vaults has survived merely in the side naves) and separate the three naves. Four more pillars can be seen in the corners, they are partially immured into the walls of the edifice. The symbolic meaning of this number is not difficult to interpret. Twelve pillars, reminding of twelve apostles, support the whole sanctuary, with four of them, symbolising the four Evangelists, seem to support the most important corners of the building. The pillars are arranged at a distance from each other, thus they do not disrupt the integrity of the naves. Actually, they highlight the verticality of the space and make us look upwards, where the vaults symbolizing the heavenly vault were shimmering with the intricate pattern of stars, flowers from the garden of paradise and other delicate ornaments. There was an abundance of wall painting in the Gothic church, it was used as a decoration both of vaults and a major part of the walls, particularly in the northern part of the church, where the windows are smaller due to the close proximity of the Convent. In the northern wall of the church partly immured Gothic confessionals have survived. They were installed within the width of the walls. This rarely used architectural element is an interesting witness of the cure of the soul performed by the Bernardines.

Scarce information, if any, has survived about other equipment and decoration of the Bernardine church constructed at the beginning of the 16th century. In the 17th-18th centuries, the interior of the church underwent several renovations, with a repeated reconstruction and adornment of the altars. Part of the artwork created during the Gothic period has survived, among them a wooden figure of the Crucifix, which aforetime had been hanging on the Great Altar (currently the Chapel Altar).

“Minor” members of the ensemble

Magnificent forms of the late Gothic style can also be seen in yet another sanctuary of the ensemble, St. Ann’s church. One can only take delight in its three-part tower, the tracery of its façade, its exquisite brickwork using the opportunities provided by shaped and profiled bricks.

The big windows installed in the thin walls of a small church (in some cases they are merely one brick wide) make the interior utterly translucent and stun us with the perfection of the construction methods.

Unfortunately, the interior elements of St. Ann’s architecture, including the vaults, were reconstructed during the renovation conducted at the beginning of the 20th century.

Two-storied residential blocks of the Convent, as usual, surrounded a small closed patio. Even though traces of the reconstruction carried out in later ages can also be identified in it, the old buildings, in particular the Convent patio, has survived its Gothic style and shape. This is witnessed by a pattern of unrendered brickwork, the walls supported by counterforts, the rows of once present large archlike windows. In the corridors of the ground floor of the Convent and the old sacristy, the premises are covered with Gothic vaults, and the wall next to the sacristy is still adorned with the compositional arrangement of the Crucified, painted at the beginning of the 16th century.

Literature: Rūta Janonienė, Bernardinų bažnyčia ir konventas Vilniuje. Pranciškoniškojo dvasingumo atspindžiai ansamblio įrangoje ir puošyboje, Vilnius: „Aidai”, 2010.

Rūta Janonienė