Books on Chain in Vilnius University Library

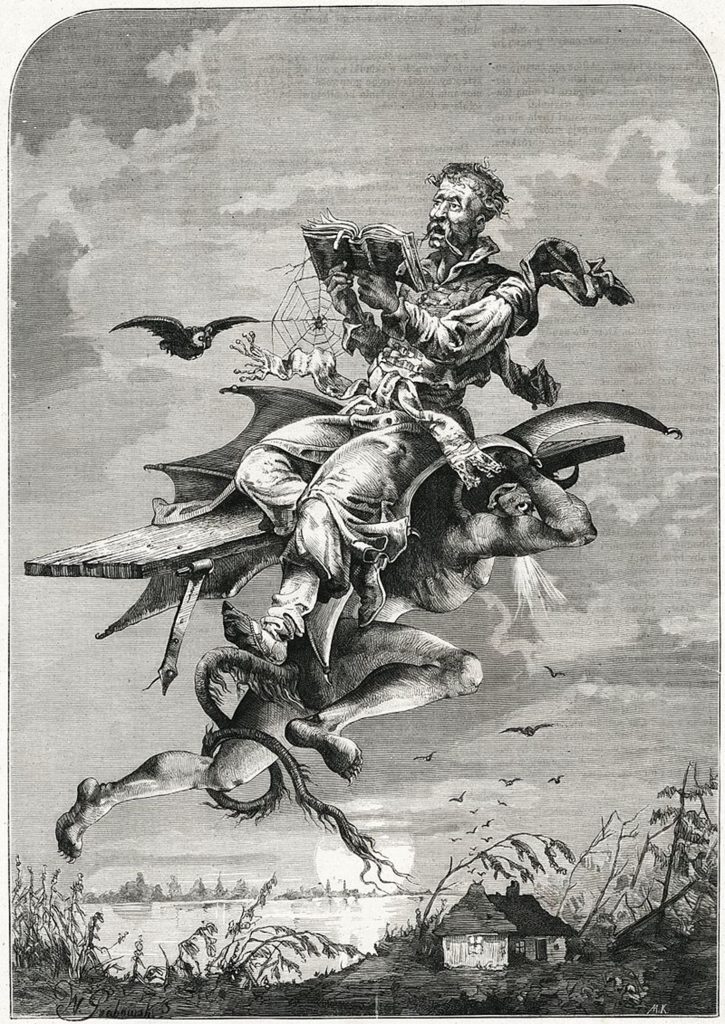

Library is a mystical place. A treasure trove of knowledge, brimming with information often difficult to grasp that both lures in and warns to keep a distance. No wonder librarians are often linked to wise men, sorcerers, prophets, and magicians.

Vilnius University Library is one of the oldest public buildings in Lithuania that has retained its original purpose.

It all started at the royal palace

The earliest collections of books in Vilnius University came from royal libraries. Most likely those had their beginnings during the Middle Ages, but we can only speak of the library belonging to Sigismund I the Old (1467–1548) with some certainty. Several of his books are still kept in the Vilnius University Library.

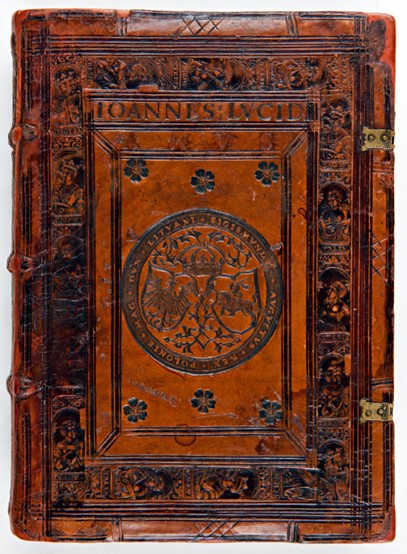

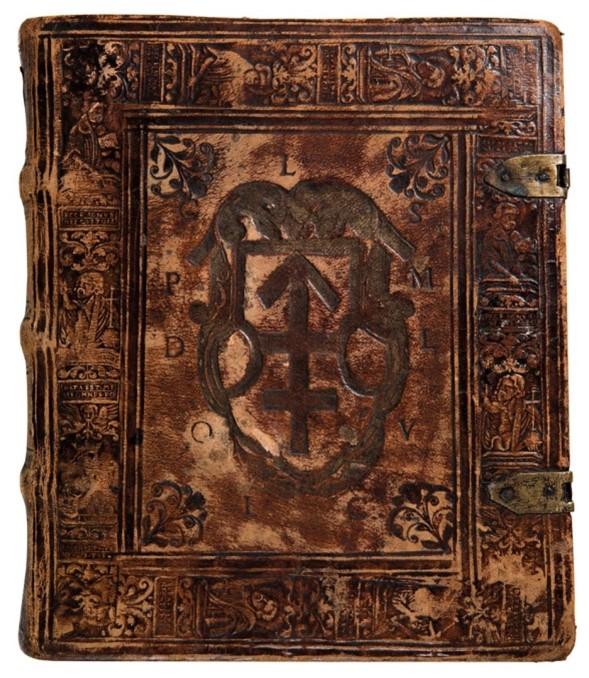

His son Sigismund II August expanded the royal library considerably. His agents purchased books in different European cities, including Frankfurt, now a home of perhaps the most famous book fair in the world. The newly acquired books were then sent to Kraków for binding, because the printers did not offer this service. Therefore, the cover was designed according to the wishes of the owner, while one had to open the book to identify it.

“

Judging by the early catalogues, most books in the royal collection (some 300 of them) were on law. Sigismund August also had dozens of books containing antique literature, travel stories, chronicles etc. He bequeathed them to the Jesuit College, established in 1570 in Vilnius.

The rich usually wanted leather covers for their books that featured marks of ownership. This is true speaking of Sigismund August’s books of which he is known to have had about 3,000. They were bound in leather covers complete with the joint Polish and Lithuanian coat of arms and the name of the owner, occasionally that of the author.

Judging by the early catalogues, most books in the royal collection (some 300 of them) were on law. Sigismund August also had dozens of books containing antique literature, travel stories, chronicles etc. He bequeathed them to the Jesuit College, established in 1570 in Vilnius. Unfortunately, but a fraction of the collection reached it after the king’s death in 1572. King’s sister Anna presented dozens of his books to her friends and relatives. Only a few of Sigismund August’s books have survived until our days.

Tradition of donating books

The library of the Jesuit College, which later became academy and then university, also received books previously owned by other well-to-do people. Georgius Albinius, the Suffragan Bishop of Vilnius, was among the first such “donors”. Interestingly, he owned several books banned by the Catholic Church, including the collected works of Origen of Alexandria edited by Erasmus of Rotterdam. Albinius died in 1570 leaving no will, therefore Bishop of Vilnius Walerian Protasewicz ordered that all his books be donated to the Jesuit College.

Over time, the flow of books was getting bigger. Bishop of Vilnius bought several other collections of books for the college. The aforementioned gift of Sigismund Augustus, although substantially smaller, reached the university only in 1579. Soon many former university students began donating their books to the library turning this into a long-lasting tradition. Among the many benefactors, Vice-Chancellor of Lithuania Kazimierz Leon Sapieha takes a place of pride. In 1655 he donated the entire collection of his father Lew Sapieha, consisting of about 3,000 volumes.

Do You Know?

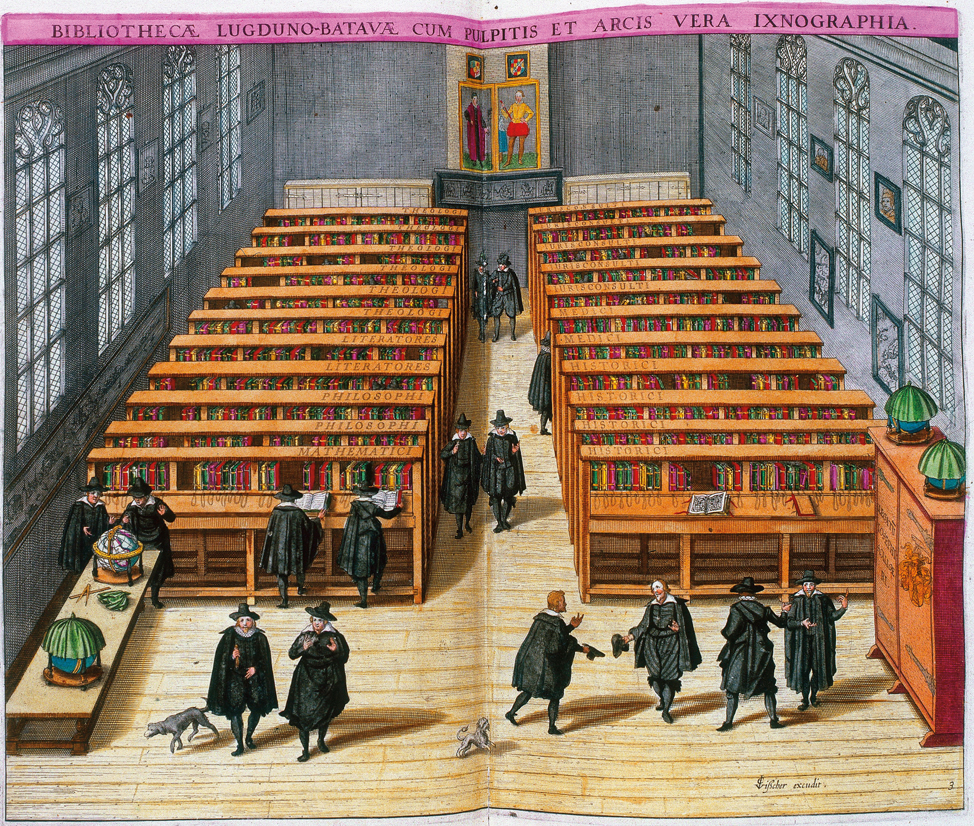

But the expansion of the library was still relatively slow even despite the fact that the university printing house was obliged to donate one copy of every book it published. Between 1579 (the founding of the university) and 1773 (when the university was temporarily closed) the number of books in the library went up less than three-fold, from about 4,500 to just over 11,000. On the other hand, the situation in some other university libraries across Northern Europe was not much different.

For example, the famous library of Leiden University had its first books donated by Prince Wilhelm of Orange in 1575. Thomas Bodley, an English diplomat and scientist, donated 2,000 volumes to the Oxford University Library in 1602.

The differences became apparent only later, as the Vilnius University library was threatened by more thefts or fires than usual. It was badly damaged during the so-called Deluge (1655–1561), when Muscovites occupied Vilnius, and the Northern War (1700–1721). Finally, in 1832, under yet another Russian occupation, most of the books were taken to Russia.

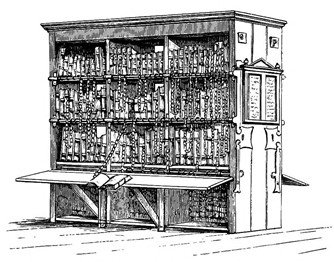

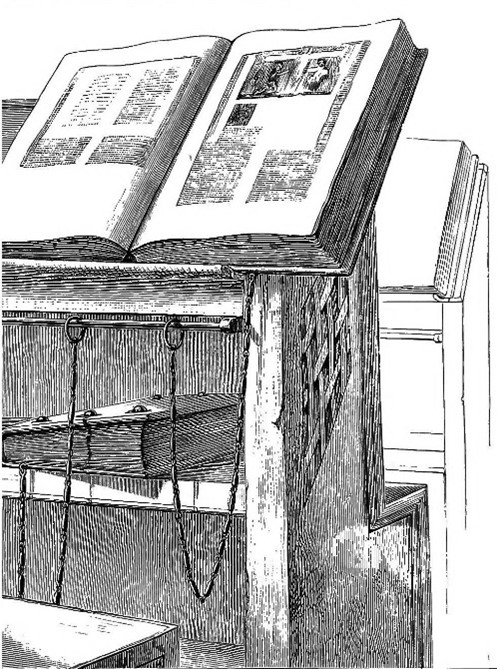

Chained books

Little is known about how the library operated between the 16th and 18th centuries. Its first chief librarian was John Hey, a Scotsman who studied philosophy in Rome and ostensibly was familiar with the principles of library management. According to the analogies in the oldest surviving books, we can surmise that the collection was separated into two parts: Libraria magna, intended for in-house use, and Libraria parva, the books available to borrow. Those were less worthy and included textbooks.

“

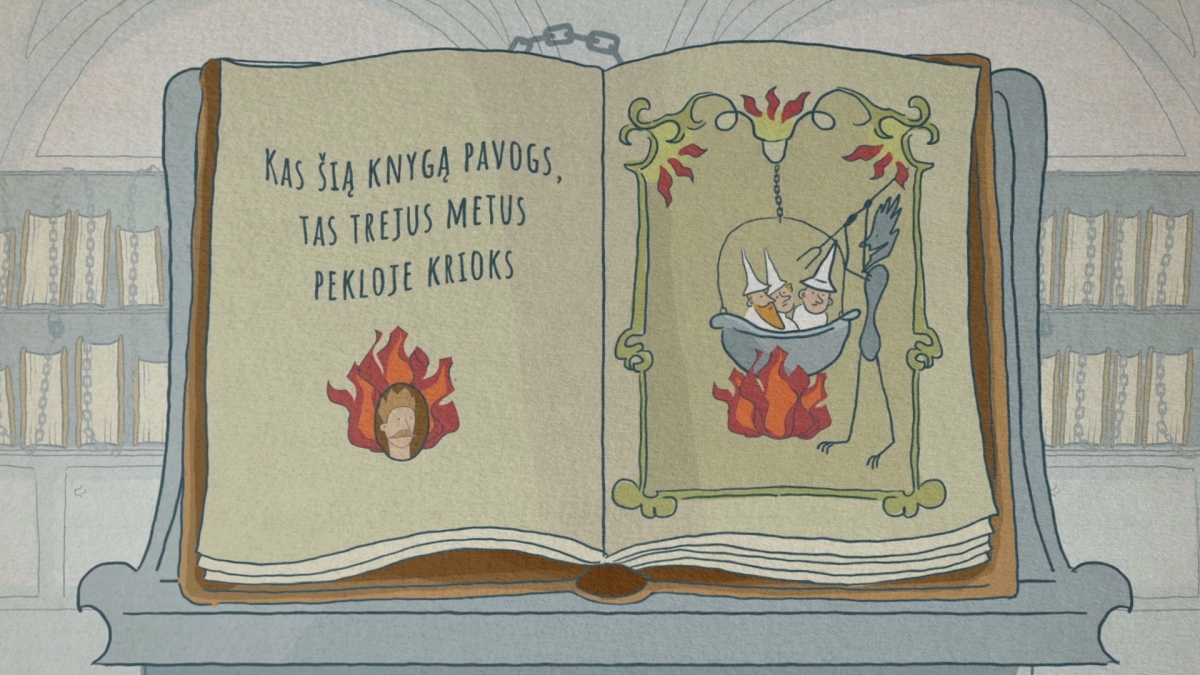

Librarians did their best to look after and preserve the books from the Libraria magna. Some of them, especially the old and valuable ones, were chained to the reading place – a pulpit or a table. Some book owners inscribed curses intended to scare the thieves away, but they proved ineffective.

Librarians did their best to look after and preserve the books from the Libraria magna. Some of them, especially the old and valuable ones, were chained to the reading place – a pulpit or a table. Some book owners inscribed curses intended to scare the thieves away, but they proved ineffective.

In all likelihood, the old university library was located in the current Smuglevičius Hall. It was perhaps not as ornate at the time, but still beautiful enough to welcome King Władysław IV Vasa in 1636 during his visit to the university.

The library moved to its present-day premises in the 18th century. Less than one hundred cabinets were required to store all the books back then. It featured a reading room that offered a quiet place for reading beside every window.

Signs from the beyond

“

Many tried to find it, but to no avail. And yet in the middle of the 17th century a student and the future rector of Vilnius University, Daniel Butwił, discovered it while working in the library. As a student of theology, he knew the book contained many forbidden passages, but his curiosity overcame his conscience. He opened it. Immediately the library air filled with sulphur gases, thundering sounds, and evil spirits.

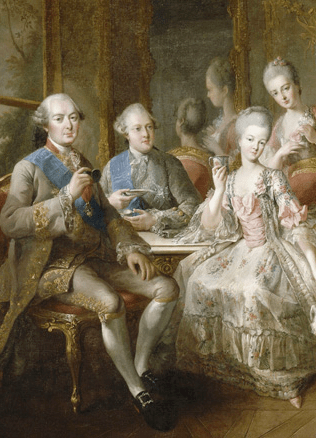

Libraries became popular in the Renaissance, when interest in ancient Greek and Roman culture and science was mixed with astrology, alchemy, magic and the search for mystic knowledge. In 1551 Barbara Radziwiłł, the beloved wife of King Sigismund II August, died. The monarch reportedly sought a chance to meet her once again and relied on the help of magicians and astrologers. One of them, Jan Twardowski, apparently arranged him a successful spiritual séance. Twardowski, known as the Polish Doctor Faustus – a man who sold his soul for knowledge, ostensibly wrote a book on magic, Liber Magnus, or The Great Book, which the king had in his library in Vilnius.

Many tried to find it, but to no avail. And yet in the middle of the 17th century a student and the future rector of Vilnius University, Daniel Butwił, discovered it while working in the library. As a student of theology, he knew the book contained many forbidden passages, but his curiosity overcame his conscience. He opened it. Immediately the library air filled with sulphur gases, thundering sounds, and evil spirits.

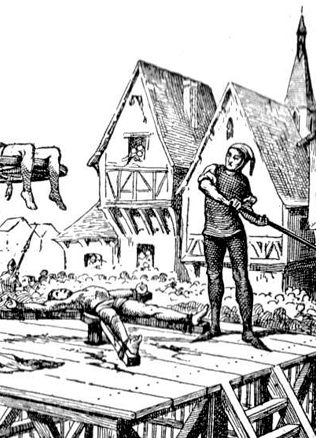

The student threw the book away and ran off. Next morning, he found tables overturned and books scattered around. Liber Magnus was nowhere to be found, but the chain was intact. Much later the book apparently surfaced in Kraków, only to vanish again. Who knows, maybe it has found a place on a shelf somewhere; hopefully, chained.

By Eugenijus Saviščevas