“Cesar means nothing today – now money is everything”: formation of the credit system in Lithuania

In the spring of 1317, Bondavid von Draguignan was accused in court of Marseille that he went on requiring to be paid after Laurentii Girardi had paid him back the main amount of the debt. Bondavid who was of Jewish origin was a creditor. There was a suspicion that he did not obey the laws that forbade practicing usury. The example mentioned is only one case of many others substantiated by the documents, which confirm the medieval stereotype that the Jews were heartless crooks. Bondavid became notorious because he was a real prototype of Shylock whom the English writer Shakespeare immortalised in his comedy The Merchant of Venice (1597) several centuries later.

Attitude of the ancient Jews and Christians to interest

Usury – charging interest on the money lent – was regarded not only as a sin but also as a crime in Christian Europe. The clergy based this attitude on the teachings of Christ: But love your enemies, do good to them, and lend to them without expecting to get anything back. <…> Be merciful, just as your Father is merciful. (Lk 6, 35-36.). Attempts were made more than once to prohibit charging interest and later to limit it up to 10 per cent per year on the amount lent.

Do You Know?

The Jews of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania turned from creditors into debtors. At that time the Church and monasteries lent the largest amounts of money. The withdrawal of the Jews from credit business can be explained by inflation – the devaluation of money. It was no longer worth lending because in reality the smaller amount was received than the amount lent. Therefore, it paid better to borrow.

Practice of the Jews, however, was different. Practice of usury was forbidden among the Jews but it allowed the Jews to charge interest from others than Jews (i.e. gojim – non-Jews): You can demand interest on the loan given to a foreigner but you cannot demand interest on the loan given to your fellow-countryman (Law 23, 21.) This different treatment of debtors gave Jews the advantage in the medieval credit system. However, it caused one of the greatest contradictions among the Christians and the Jews, which was clearly expressed in the provoking remark of Shylock about his rival Antonio:

How like a fawning publican he looks!

I hate him for he is a Christian,

But more for that in low simplicity

He lends out money gratis and brings down

The rate of usance here with us in Venice.

If I can catch him once upon the hip,

I will feed fat the ancient grudge I bear him.

He hates our sacred nation, and he rails,

Even there where merchants most do congregate,

On me, my bargains and my well-won thrift,

Which he calls interest. Cursed be my tribe,

If I forgive him!

However, the norms regulating moneylending were violated. Bankers-Christians could conceal large interest by not indicating the amounts, which they had lent, and showing only those which were paid back. The Jews who lent money stirred up greater hatred because they lent smaller amounts to the broad public. Despite all that, the role of the Jews in the formation of the credit system and banking in Europe was of significance.

“Blood of economy” gushed

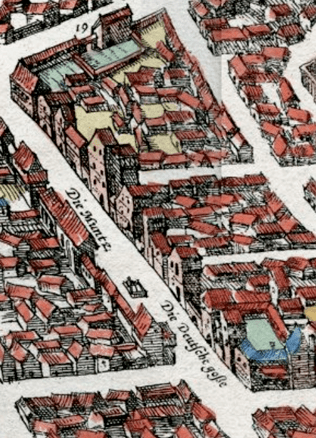

Religious tolerance of the society of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and weak economy of the State during the late Middle Ages opened broad economic possibilities, especially those of crediting activity, to the Jews. The latter started to settle there in the 14th century, in 1388 Jewish communities of Brest and Grodno were already created in Lithuania. Having settled in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, the Jews adapted their skills of economic activities, including those of credit, there.

The privilege granted by Vytautas the Great to the Jews in 1388 defined namely trade and credit – lending money – as possible forms of their economic activity.

This was the most important activity of the Jews in Western Europe. The Rulers and the nobility of Lithuania found this new social group of use because the need for cash, which was used for representation and military purposes, constantly increased. The Jews also imported luxury goods (fabric, spices, expensive articles made by craftsmen), which the ruler wanted, and the strengthening nobility enjoyed. The Jews became a social group in Lithuania, which undertook credit operations and laid a foundation for this business.

The credit system formed in Lithuania at the end of the 14th century after the first Jewish communities in Brest and Grodno had formed. The sources, however, provide little information about credit operations in Lithuania until the second half of the 15th century.

The debt of the Ruler and the nobility to the Jews is specified as a possible reason of driving the Jews out of Lithuania in 1495.

The account books of the court of the Grand Duke of Lithuania Alexander show that the Ruler was constantly short of cash to settle accounts with the courtiers and merchants therefore he had to borrow. Town-dwellers who carried out trade operations also needed money. The French theologian Alan of Lille defined exactly this situation of the 12th century: “Cesar means nothing today – now money is everything”. The importance of money was on the increase and soon it turned into the symbol of the town.

The Jew’s advantage over other creditors was that they did not always demand he money lent to be paid back in cash. Sometimes the debt was paid back in products: salt, honey, corn. Since monetary relations were not developed yet, for the treasury of the state it was more convenient. The Rulers of Lithuania did not always find creditors in their country therefore they borrowed from abroad. For example, Vytautas, when fighting against Władysław II Jagiełło in 1390–1392, borrowed from the Teutonic Order.

The debt is not a wound and it will not heal…

It is necessary to mention the distinguished Jewish businessman of the second half of the 15th– the beginning of the 16th century in Lithuania – Michał Jozefowicz. His brother Abraham, having adopted Christianity, even became Treasurer of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. Scanty credit sources of Michał Jozefowicz show that this activity created lots of difficulties to him. The acts that have survived testify to the fact that crediting with goods and money was carried out, due to the debts that were not paid back the Jewish businessman had a lot of trouble. He had to look for the hiding debtors, appeal to courts, and wait for the debts to be paid back. The businessman provided credit services because he sought to win favours with the Grand Duke and receive more privileges. The Ruler Sigismund the Old was among Michał Jozefowicz’s debtors who was in the habit of paying back debts from rent (he rented some objects – a customs or an inn).

The largest part of the credit contracts was confidential, therefore they did not get into the sources.

The acts revealing the businessman’s crediting activity are late and show his financial experience.

The bill of exchange (Germ. wechsel) was closely related to credit operations. Bills of exchange were not widespread in Lithuania, however, the bill of exchange issued by Jagiełło to Vytautas is known thereby the latter was obligated to pay him 500 pure silver roubles. Bills of exchange were not trusted in Lithuania therefore the Ruler often pledges his estates for debts. In this way land-tenure of some noblemen expanded. The Jews demanded that the debtors should give them a pledge rather than a bill of exchange.

Hence, though the formation of the credit system in Lithuania was late as compared with Western Europe, it was already known from the end of the 14th century. Jews were the most important creditors in Lithuania in the 15th – 16th centuries. Later the nobility, the Church and monasteries became engaged in this business. Credit operations were important to merchants and the development of the towns, the Ruler who borrowed for military purposes and the noblemen who were concerned about representation. From the 15th century the need for cash was constantly on the increase in Lithuania.

Arvydas Maciulevičius