Clientele relations in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania: mutual benefit

The roots of the clientele system as a social institution go back to antiquity. Even Cicero, when speaking about the oldness of Roman clienteles, underlined that it was Romulus himself who introduced it in Rome. The basis of the clientele system – the relation between the patron and the client – functioned in Europe during the entire period of Modern Ages and regulated the societies of that time. The historians, when characterising the clientele relations, especially those that were typical of the 16th – the 18th centuries, referred to them as a “key to a social position”, “the oil that assured smoothness of the life of society” and the like. What was the essence of these relations?

Career by exploiting personal connections

The relations between a client and a patron were noted for their personal nature, the participants occupied an unequal social position in society, and their political and economic possibilities differed considerably. Informality is characteristic of the relations of both sides, such relations were not legalised but based on an unrecorded agreement. A weaker partner undertook to serve faithfully, to provide various services for certain remuneration, protection, intermediation seeking for material and non-material good. And the patrons had to provide all possible support. The relations between the client and the patron were long-term and constant. Favourable conditions were needed for the clientele system or the informal government structure to function. The most important thing was that certain resources, social relations in society should be monopolised, and potential clients could make use of the help of the patrons only who demanded personal loyalty.

“

From the middle of the 16th century, despite the phenomenon of “lateness” of the state, favourable conditions (though different from those in Western Europe) for the clientele system formed in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania too.

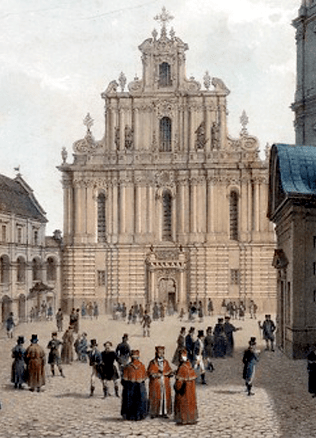

From the middle of the 16th century, despite the phenomenon of “lateness” of the state, favourable conditions (though different from those in Western Europe) for the clientele system formed in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania too. Governance in Lithuania had no features of absolutism and gradually weakened. Following the 1564–1566 legal and administrative reforms and the 1569 Union of Lublin, the Council of Lords “kept an eye” on the Ruler of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and later the senators of the Commonwealth of the Two Nations did that. After the Jagiellonian dynasty died out, elections determined unstable power of the king. Due to a poor network of communications, a small number of a population in the territories, the Ruler’s rare residing in Lithuania, it was difficult for the central government to reach the province of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. The system of distributing offices, however, remained unchanged, traditionally the Ruler appointed his supporters and the people patronised by the latter to higher central or local offices. Post-reform or formally democratised land courts were further governed by the Lithuanian lords (not only directly but also through their protégé). Hence, due to weak power of the monarch and the surviving abundant influence of the nobility, clientele relations functioned from the middle of the 16th century in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania already.

The state’s puppeteers

Magnates could have been and were the main patrons in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. As in France or other European countries of that time, from the middle of the 16th century, personally or exploiting personal connections in the court they acted as intermediaries for their own people, and in provinces they independently created a regular network of informal authority. The clientele system assured a firm socio-economic position for the magnates, enabled them to remain in the ruling elite.

“

Clientele of the nobility of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania could give an answer to J. Hexter’s question about the noblemen of England who remained in power for several centuries: “How did they manage that?”

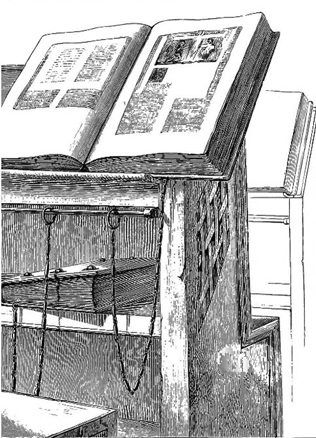

Clientele of the nobility of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania could give an answer to J. Hexter’s question about the noblemen of England who remained in power for several centuries: “How did they manage that?” The data of the serial historical source – the Lithuanian Metrica of the 16th century – clearly shows that. There is hardly any new office or privilege of the land holding granted by the ruler at the request of the receiver only, without intercession of the magnates of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. The exception was the King’s permits to set up inns. And according to the number of intercessions of the patrons, the books of Metrica can conditionally be divided into the patronage books of Mikalojus Radvila Juodasis (Mikołaj “the Black” Radziwiłł) (No. 35–49), later Mikalojus Radvila Rudasis (Mikołaj “the Brown” Radziwiłł), Ostafijus Valavičius (Ostafi Wołłowicz), the Elder of Samogitia Jonas Chodkevičius (Jan Karol Chodkiewicz) (No. 50–70) and other noblemen. The most influential patrons in the baroque epoch were Pac and Sapieha families.

Specificity of the clientele system of a concrete magnate was determined by the patron’s position in the state, his personal interests and possibilities, even his personality. The clients were concerned about getting into the clientele of the magnates who were most influential according to offices, managed latifundia and their lineage. It still remains unclear whether it was easier for a client to find a patron or vice versa. The number of the clients who served separate noblemen was different, and at different periods, depending on the patron’s position in the state, it changed. The most influential persons in the state, e.g., Palatine of Vilnius Mikołaj “the Brown” Radziwiłł (around 1515–1584) could have about several hundred clients loyal to him at a time, who acted in favour of the magnate in the Ruler’s court or in the province of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.

The example of the activity of the clients of one group of Mikołaj “the Brown” Radziwiłł – the King’s secretaries – can show a real functioning of the clientele mechanism. From 1548 till his death in 1584 the nobleman constantly had people who were well-disposed towards him in the Secretariat of the Ruler. The number of such secretaries (mostly from the Lithuanian Secretariat) devoted to the nobleman totalled 15.

“

When the secretary made a career owning to the magnate and when he became, for example, an official of central government, the clientele relations turned into friendly ones.

This office was the beginning of the career for many of them, therefore their relations with the Mikołaj “the Brown” Radziwiłł changed. When the secretary made a career owning to the magnate and when he became, for example, an official of central government, the clientele relations turned into friendly ones. The letters show the way the secretary could become the nobleman’s client. For example, Mikołaj “the Brown” Radziwiłł offered his friendship and patronage point-blank in a traditional form in a letter (which was noted for its kind style) of 1565 written to Secretary Mikalojus Naruševičius. After being asked to become a patron of the Polish Secretary Jerzy Podlodowski, Mikołaj “the Brown” Radziwiłł agreed immediately, and in 1550 answered in a classical wording typical of the relations between the patron and the client: “Not to neglect in any affairs, joyful or sad”.

Social symbiosis

Letters and gifts testify to the fact that Mikołaj “the Brown” Radziwiłł valued loyalty, devotion, social-awareness of these clients. Ignoring religious differences Mikołaj “the Brown” Radziwiłł supported the Catholic Augustyn Rotundus, the Orthodox Michal Haraburd and the Lutheran Wenceslaus Agrippa. The nobleman constantly interceded for the secretaries, who became clients, to the Ruler. Mikołaj “the Brown” Radziwiłł asked the King for higher offices for five persons, to increase salary for one person, to give permission to buy out lands or confirm the ones that were in their possession for two persons, he spoke for one person in court and asked his nobilitation to be confirmed.

“

The King’s secretaries were important to the magnate not so much for their direct offices but sooner for important information they provided.

It was more than once that the clients of the magnate of this group received different gifts from the influential patron. The King’s secretaries were important to the magnate not so much for their direct offices but sooner for important information they provided. Being nearest to the Rulers, the clients informed the nobleman of the most important news of the court, the news about the Rulers’ health, their attitude to Radziwiłł and especially about his policy. The Kings’ secretaries, like the clients of Mikołaj “the Brown” Radziwiłł, performed specific tasks in the court, which the magnate entrusted them with. Finally, the panegyric works of the King’s secretaries Venceslaus Agrippa, Kiprijonas Bazilikas, Pranciškus Gradauskas, Stanislovas Košutskis or Elijus Pielgrimovskis glorifying patron Mikołaj “the Brown” Radziwiłł show that.

Raimonda Ragauskienė