Early Archives of the Nobility in the 16th and 17th Centuries

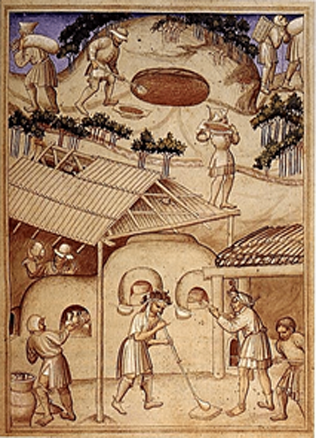

By accepting Christianisation, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania made a huge qualitative leap in many areas of social life. The industry of writing was one of the spheres in which European experience was introduced. During the years of Vytautas’ reign (1392–1430), a potent chancellery of the grand duke was established. It began issuing plenty of various documents related to foreign diplomacy and local issues. Vytautas’ chancellery became an example to similar institutions that the country’s aristocrats began introducing in their private estates. First documents compiled in private chancelleries of the nobles date back to the middle of the 15th century. They discontinued the monopoly of the grand duke’s chancellery. The process was accompanied by the accumulation of the office production that was important for private individuals and institutions. Therefore, the period between the middle of the 15th century and the late 16th century was the time when early archives of the modern era began to take shape.

Family history in a tiny chest

Private archives of that time belonged to the nobility and aristocrats. Scanty privately kept documents of city residents of the GDL represent rare exclusions; peasants had very few documents.

In the late 18th century, free peasants kept their private documents, usually the papers granting their freedom. In the 18th century, the free man named J. Juodis kept four documents attesting his family’s freedom issued back in 1574. Michalczy from the Tarvainiai village in the estate of Viduklė had his family’s liberation papers of 1610 and 1773. The Jakszt peasant family kept receipts and agreements between them and their former owners dating back to 1662.

A private archive from the old period of the GDL represented a specific collection of archive documents. A direct link to land ownership and to the Chancellery of the GDL was its characteristic feature. Documents issued by the Chancellery dominated in private archives. The number of document types issued by the Chancellery reached almost 50 in the 16th century. It prepared documents related to particular transactions or court cases in line with the set rules of record keeping. Private collections of the nobility were pragmatic.

For their creators and owners, the collections represented the treasuries of their rights and knowledge. The correspondence left for keeping as well as genealogical and other materials revitalised the hearts of the nobility.

First historical sources referring to small collections of documents date back to the early 15th century. Representatives of the GDL’s aristocracy used to carry documents together with them in travel bags or in chests. They did so not only because the number of documents was small, but also because the documents were very important in the turbulent years of the early 15th century. Kristinas Astikas, the castellan of Vilnius and the progenitor of the Radziwiłł family, used to carry tiny wads of documents with him in the beginning of his career in the early 15th century. Fiodor Olgierdowicz and his son Sanguszko Fiodorowicz, the progenitors of the Sanguszko family, also followed the similar tradition. Judging by the descriptions of archives that refer to the earlier collections of documents, one can presume that the early collections of the Radziwiłł family and the Sanguszko family consisted of just several dozen documents. Most probably, they included correspondence too.

From several documents to stationary archives

At the turn of the 16th century, archives of aristocrats were rapidly growing bigger because of the high official posts held by their owners and the documents they would receive from the grand dukes. Even the widespread practice of dividing archives between members of the extended family in accordance to the inherited lands could not stop that process. New lines of the extended family used to continue accumulating their own collections of documents. A good example the history of the archive of the Radziwiłł extended family. Descendants of Kristinas Astikas, the progenitor of the family, had one of the largest private archives in the GDL one hundred years after Astikas’ death. The Radziwiłł family branch from Biržai and Dubingiai kept their privileges and legal documents in ten large chests in the treasuries of the castles in Alunta and Dubingiai in the late 16th century before moving them to the castle of Lubcha in the early 17th century. They kept the documents of the Evangelic Reformat churches and those of the Orthodox churches separately in 19 other chests. These archives only included documents related to land ownership and religious matters. The family also kept large amounts of public materials of the GDL and collections of correspondence. Not surprisingly, the family kept its archive documents in as many as 119 chests of various sizes around 1666.

One small chest was enough to keep the archive of the Radziwiłł family branch from Biržai and Dubingiai in the middle of the 15th century. Their archive grew to well over 3,000 documents kept in several dozen chests in the 17th century.

The middle of the 16th century marked the beginning of the new stage in the history of document collections owned by the nobility, because they started accumulating documents on a massive scale. An average noble kept his private archive in chests of various sizes the number of which could reach from several to several dozen with several hundred to two or even three thousand separate documents inside. Wealthy and middle-rank nobility kept up to two hundred documents. Lower-rank nobility usually had sup to 20 documents kept in smaller chests. Private archives included typologically varied materials the majority of which were legal documents related to land ownership. Family documents included testaments, inventories of movable property, correspondence between family members and genealogical documents. In addition to that, the nobility accumulated collections of public – state and official – documents, but the materials related to daily affairs dominated their archives.

Preserving documents of vital importance

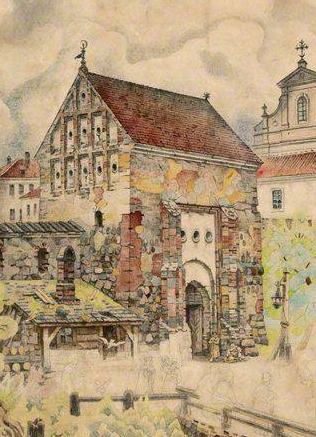

Aristocrats and the nobility chose different places for keeping their private collections of documents depending on the size of the archive, social status and wealth of the owner, and the need to ensure higher security. Aristocrats kept their archives in their main stone or wood residences and in stone houses in cities. In the late 16th century, sometimes they already had special rooms for their archives, as the example of the Radziwiłł family shows. Aristocrats had document storages ensuring higher level of security, because their archives featured special doors with locks, barred windows and solid chests for papers, sometimes made entirely of iron. Their culture of document keeping was similar to that commonly accepted in Europe. Other representatives of the nobility usually kept their archives inside their wooden estates or in stone houses in cities. Cellars, darkrooms, “light” rooms, barns and granaries were popular places for keeping documents. People who had no proper room for their archives, entrusted vital documents to wealthier nobles, relatives, and sometimes to city dwellers.

People kept their documents in different containers, chests and boxes of various shapes and sizes in the first place, but also sacks, bags and special furniture. Locally made wooden chests – often painted and bound – were the most popular document storages in the 16th century. The level of culture of document keeping was quite low among the 16th-century nobility. Although their archive documents were vitally important, the nobility usually invested very little to ensure their security. First purpose-built treasuries for archives emerged in the 18th century. Meanwhile in the 16th century the nobility used living rooms and other ordinary premises to keep their documents.

People did not care much about the security of their papers in the 16th century. This is why we have very few documents from that time and earlier years.

The nobility of the GDL were very often unable to preserve their archives from damage in the 16th century. Raging fires sometimes destroyed half or even larger parts of private archives.

By the second half of the 16th century, the nobility had already accumulated rich private collections of documents and did their best to preserve them. Judging by the contemporary or slightly later descriptions of these collections, they only included the most important documents that nobles needed almost daily. The inventories never refer to public documents and collections of correspondence, neither they mention the so called silva rerum materials the nobility began accumulating in the late 16th century. During the early stage of formation of private archives, the nobility used to gather and to preserve all types of the abovementioned materials. They were particularly respectful when dealing with the correspondence received from rulers and influential aristocrats. However, the information about private collections of documents in the 16th century often represents a certain “reality trap”, because it reflects only part of the reality.

Literature: R. Ragauskienė, Privatūs XVI a. Lietuvos Didžiosios Kunigaikštystės didikų archyvai: struktūra ir aktų tipologija, Istorijos šaltinių tyrimai, sud. A. Dubonis, Vilnius, 2010, t. 2, p. 85–108.

Raimonda Ragauskienė