How to Invite a Cruel Death in Old Vilnius: the Story of Franco de Franco

Anyone standing in the middle of the square of the Vilnius Town Hall will see quite a lot, even without a considerable effort. The classicist building of the Town Hall; the crown-topped St Casimir Church; the pavement of the ancient square; and several old streets, leading to Ruthenian and Latin parts of the city. The streets would surely tell much more, if only they spoke.

Nowadays the Town Hall Square rarely hosts big public events, but several centuries ago it was not so. A closer look at Civitates Orbis Terrarum, the famous 16th-century map of world cities by George Braun, reveals a whipping post in the centre of the square. It was there that thousands of offenders faced punishment.

Every man has a story. Here’s one of them, a nearly forgotten one, but well worth reminding.

The colourful procession of Corpus Christi

Since the early Middle Ages, urban life has been closely related to churches. Vilnius was a home for a number of confessions and their homes of worship, including Catholics, Jews, Lutherans, Eastern Orthodox Church, and Calvinists. Sometimes their proximity led to conflicts.

Do You Know?

From the mid-15th century onwards, Corpus Christi grew ever more popular, its culmination being a splendid procession. The ritual remained almost unchanged until the early 20th century. The Corpus Christi is celebrated nine weeks after Easter, i. e. between May 25 and June 23. Several guilds uniting artisans of Vilnius made its attendance compulsory, by inscribing this obligation into their guild statutes.

After the Jesuit Academy was opened in Vilnius, many students joined the procession.

The centrepiece of the procession was a huge golden cross decorated with diamonds, beautifully glistening in the sun. It was a colourful and pompous event, celebrated with church hymns, and so it caught the eyes and ears of many residents of Vilnius, including religious dissidents. Crowds followed the procession, as a contemporary witness attests: “Catholics, Jews with wives and children, Ruthenians, Tatars, and Protestants – they all abandoned their daily chores and watched the procession. When asked, they would say: ‘We came to see the Catholics worship their God.’”

The route remained the same since the late Middle Ages. The procession, featuring banners and images of the saints, would start after celebrating the Mass at the Cathedral and advance towards the church of St Johns winding down the streets decorated with flowers and green garlands, flags fluttering in the wind, the participants bore images of the saints and were lined up in strict hierarchy. Upon reaching the church of St Johns the procession stopped for a player and a sermon before continuing towards the Town Hall Square. There they would stop to pray for a second time, then continue towards the chapel of St Mary Magdalene, and end up at the cathedral. After at least two rests for prayer, the procession would return to the Cathedral.

Exquisite splendour and strong passions

Since the late 16th century, as tensions between Catholics and Protestants were rising, the latter criticised the Catholic cult of Holy Sacrament that constituted the very essence of the Corpus Christi procession.

“

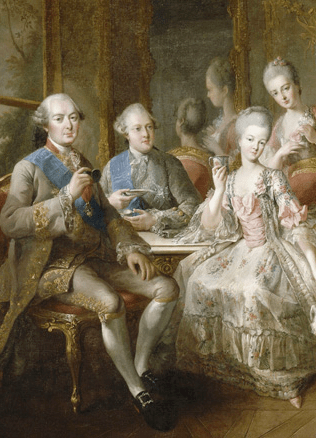

Almost one year later, on 2 June 1611, the traditional Corpus Christi procession was even more sumptuous than usual. It was marked with the presence of royalty: Queen Constance of Austria, her son Władysław, the future King of Poland and the Grand Duke of Lithuania, and, arguably, Jan Kazimir who succeeded him, took part in the ceremony. The royal family have been staying in Vilnius since 1609, because King Sigismund III Vasa was personally leading the siege on Smolensk.

The spirit of toleration was waning, religious tensions grew stronger, and heated emotions led to action. On 1 July 1610 a huge fire broke out in Vilnius. It raged over the western part of the city, inhabited by Catholics, devastating the neighbourhood and many churches standing there. The fire spared the eastern part, where the Calvinist church stood. It did not take long for rumours to spread throughout the fire-stricken city, people were talking that Calvinists scorched it.

Almost one year later, on 2 June 1611, the traditional Corpus Christi procession was even more sumptuous than usual. It was marked with the presence of royalty: Queen Constance of Austria, her son Władysław, the future King of Poland and the Grand Duke of Lithuania, and, arguably, Jan Kazimir who succeeded him, took part in the ceremony. The royal family have been staying in Vilnius since 1609, because King Sigismund III Vasa was personally leading the siege on Smolensk.

In addition to that, dozens of royal courtiers joined the procession alongside the bishop of Vilnius, senators, and members of the Supreme Tribunal. Piotr Skarga, the prominent preacher and the first rector of Vilnius University, is also known to have taken part.

The Italian that insulted Catholics and the royal family

At noon, when the procession reached the Town Hall Square, a man, sword in hand, emerged beside the temporary altar erected right at the whipping post. Aloud and clearly wishing to insult the Catholics, he started arguing that the Eucharist was not the body of Christ and that by believing the opposite the Catholics were simply ignorant. This, obviously, made the Catholics furious. They captured the man and took him to the Town Hall for interrogation. The man confessed he was Franco de Franco, hailing from a small town belonging to the Venetian Republic. In Vilnius, he stayed with Samuel Petkewicz, a well-known Calvinist. Just hours prior to the incident Franco de Franco attended a Calvinist service where a local preacher made an abundance of critical remarks regarding the Eucharist.

“

They captured the man and took him to the Town Hall for interrogation. The man confessed he was Franco de Franco, hailing from a small town belonging to the Venetian Republic.

Bishop of Vilnius Benedykt Woyna took it personally. It seems that the royal preacher Piotr Skarga did as well. They wanted the case to be heard by a secular court of law. But the judges saw no major wrongdoing in Franco de Franco’s behaviour, adding that his sword had harmed nobody. The conflict had to simply blow over.

The sword that led to quartering

But the Catholics sought revenge. They knew Franco de Franco did not have influential friends in Vilnius, therefore the bishop accused him of lèse-majesté the royal family by holding an unsheathed sword in their presence. If proclaimed guilty, Franco was to be quartered. Judges, on the other hand, suggested that he admit his errors and ask for forgiveness. But the Italian declined, because the full repentance also asked of him something that he simply could not do: adopting Catholicism.

“

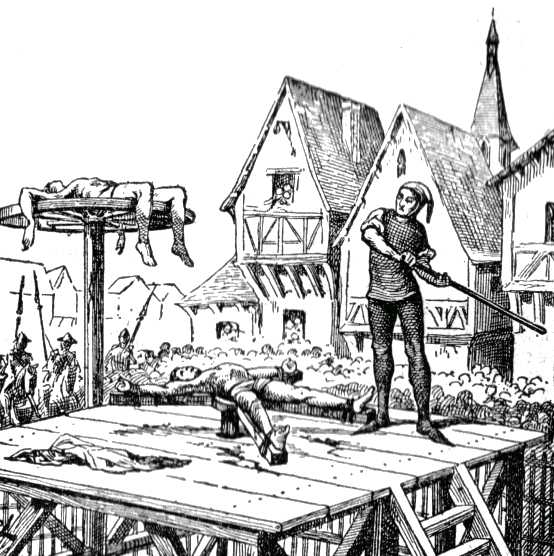

He was executed on June 30, at night, in the dungeon of the Town Hall. In a brutally symbolic way, the executioner started off by ripping his tongue out (for the blasphemous words) and then quartered the body and hung it, in parts, on the whipping post. Hours later, though, someone stole them, burned down and scattered the ash over Neris.

He was executed on June 30, at night, in the dungeon of the Town Hall. In a brutally symbolic way, the executioner started off by ripping his tongue out (for the blasphemous words) and then quartered the body and hung it, in parts, on the whipping post. Hours later, though, someone stole them, burned down and scattered the ash over Neris.

But the unrest continued. Catholics kept blaming Calvinists of conspiracy, while Calvinists were angry about the biased court ruling: according to the legal practice the senatorial court had no right to rule over Franco’s case, let alone proclaim the capital punishment. Calvinists worried that such precedent brings danger upon all non-Catholic residents of Vilnius. Soon such worries were proven to be right. Just weeks later, on 2 July 1611, a religious riot among Catholics and Calvinists erupted in Vilnius. This was the end of confessional coexistence and the beginning of an era marked by religious hatred.

By Eugenijus Saviščevas