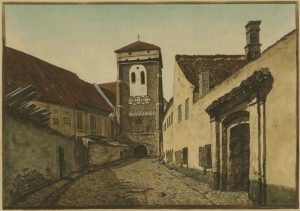

Taverns on Šv. Mikalojaus Street

Four centuries ago, taverns functioned as centers for services and communication nodes. People gathered there to eat and drink, but also to exchange news, and conclude business deals.

A few types of such institutions functioned in and around Vilnius. Inside the city proper, taverns usually served food and drinks, but on the outskirts, the larger inns often offered accommodation too.

Selling home-made alcoholic beverages earned a tavern most of its profits. Beer was by far the most popular drink, distantly followed by mead and vodka. It is no coincidence that the year 1552 saw the inauguration in Vilnius of the maltsters’ guild. It is known that one tavern belonged to malster Peter on Šv. Mikalojus Street.

Learn more about the taverns of old Vilnius by clicking this link.

Address: Šv. Mikalojaus St.

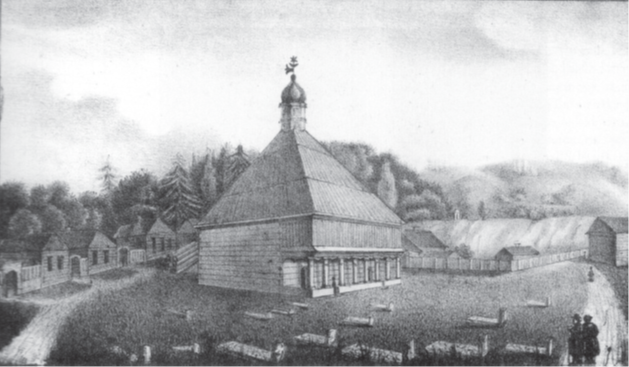

Reformers Cemetery

In 1640, King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania Władysław IV Vasa (1595-1648) issued a decree, by which Evangelical Reformats were moved behind the city walls, near the current-day Pylimo Street. At first, Evangelical Reformats built a wooden church and established their cemetery. In 1682, a wooden church and cemetery were damaged. To compensate for the losses, King and Grand duke Jan Sobieski allowed the church to be rebuilt.

In 1731, Evangelical Reformats were ordered to evict their cemetery further from the city's center. However, this cemetery was used till the 1830s. The new cemetery was founded on a nearby hill. In 1835, a current Evangelical Reformats church was built on Pylimo St.

Learn more about the first evangelical resident of Vilnius by clicking this link.

Gates of Dawn Street

The Gate of Dawns street led to Medininkai, Grodno and main Polish Crown cities. The street is surounded by different denominations Christian house of worships. Due to this reason, in 1611, after a victorious military operation that brought Smolensk back under Polish-Lithuanian rule after 97 years, King of Poland and the Grand Duke of Lithuania Sigismund III Vasa decided to enter the city via the Gate of Dawn.

Learn more about Sigismund Vasa’s Triumphal entry by clicking this link.

L. Gucevičius Square

In the past, the current L. Gucevičius Square and Presidential Garden looked much different than it looks now. In the place of current L. Gucevičius square used to be a small cemetery. It is known, that at the beginning of the 16th century a column with the image of Crucified Jesus. In 1543 Bishop of Vilnius Paweł Holszański built a Chapel of St. Cross. In 1635, Brothers Hospitallers of Saint John of God settled near the church of St. Cross.

In the spring of 1651, a group of Franciscans, spades in their hands, walked to the monastery of the Order of the Hospitallers of Saint John of God, in the vicinity of the present-day Presidential Palace. The Fatebenefratelli brothers must have been greatly surprised when they saw Franciscans shoveling in their cemetery. Learn more about the first archeologic excavations in Vilnius by clicking this link.

Address: S. Daukanto Sq. 1

St. Cross Church and Bonifrater Monastery

In 1635, when the Brothers Hospitallers of Saint John of God arrived in Vilnius, the then bishop of Vilnius settled them placed them next to the Gothic Chapel of St. Cross. The Bonifrater brothers were the only order, which took care of sick people. Brothers of the order, without vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience, which were given by all monks, the Bonifraters swore to take care of the sick.

However, this path was not suitable for everyone. Perhaps the brother Apollinary's story illustrates that this path was suitable not for everyone. Learn more about the path illustrated by Brother Apollinary’s path by clicking this link.

Address: S. Daukanto sq. 1

Gediminas’ Tower

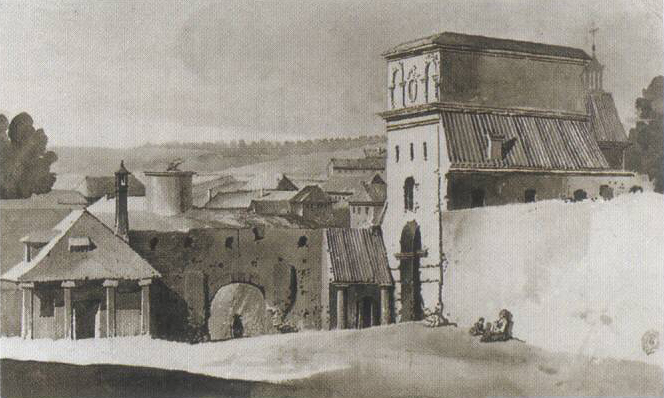

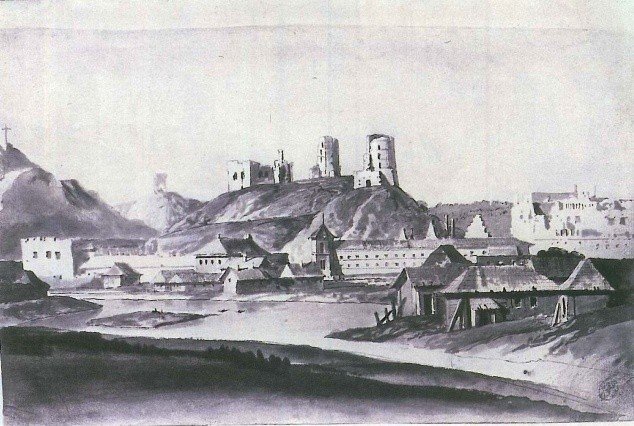

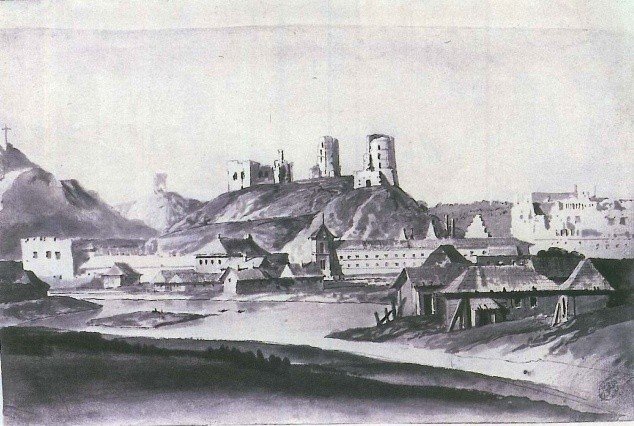

According to historians and archeologists, a wooden castle on Castle Hill was built in the 1280s. Two opinions exist regarding the question of when the Upper Castle had been built from bricks. Some experts date the appearance of brick structures to the first half of the 14th century, while others think - that it happened at the end of the 14th century.

The maintenance of the upper castle was taken care of by a special officer - the castle's supervisor (pol. horodniczy). Till the end of the 15th century, the upper castle served as a ruler's main residence. In the 16th century, a prison was established in the Upper Castle.

During the Muscovite occupation, the Upper Castle was heavily damaged, and later its condition gradually deteriorated. At the beginning of the 19th century, only the Gediminas tower and residence's ruins remained, which survived to this day.

Learn more about grand duke Gediminas and his diplomacy skills by clicking this link.

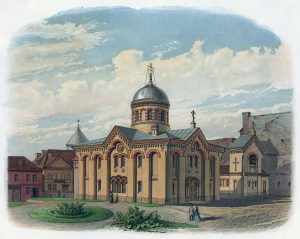

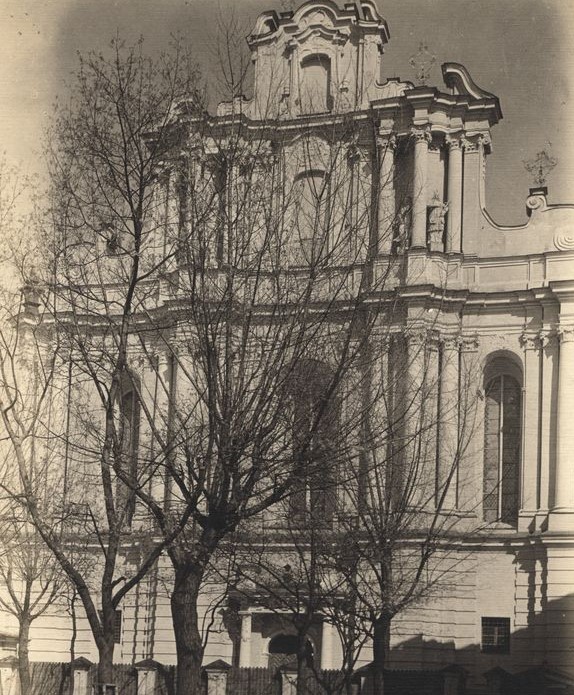

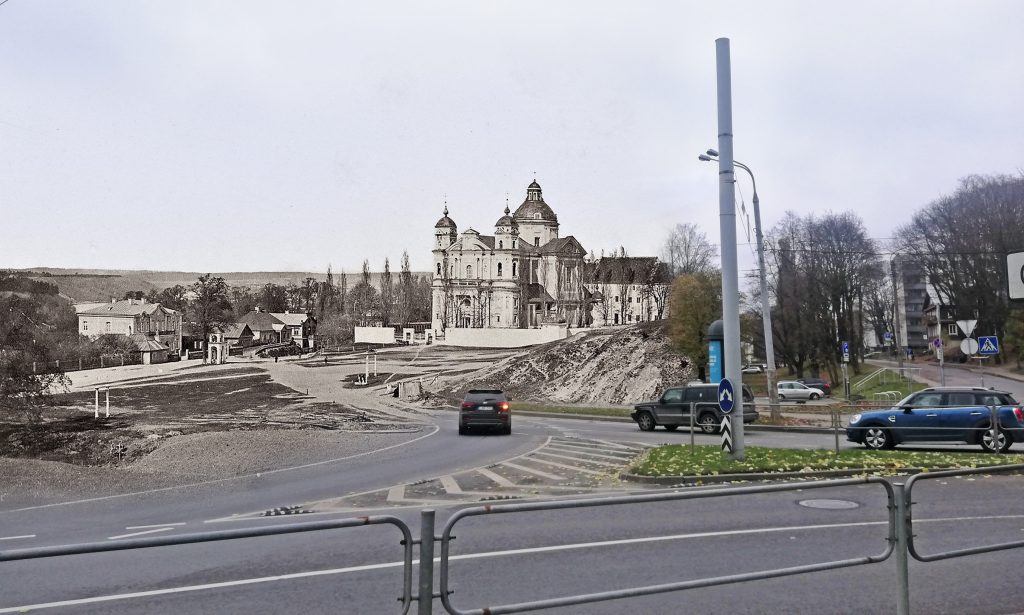

Former Evangelical Reformed Church

The Reformation movement reached the Grand Duchy of Lithuania from Western Europe in the 1530s and brought with it many changes – remarkable, but not always positive, as the tensions between Catholics and supporters of Reformation ideas gradually grew, leading to some serious clashes.

In 1579, Evangelical reformats built a church in the northeastern part of the city (currently - A. Volano St.), near the Bernardine and St. Anne's churches. The Evangelical Reformed Church operated in this place until 1639. From 1640, their church was moved outside the city walls, in the present Pylimo str.

The Easter of 1599 was marked with blood, as a battle rose between Catholics and Reformats. According to the Catholics, Reformats locked Samogitian Bishop Merkelis Giedraitis at the Cathedral along with other Catholic residents. The confusion later turned into a fight, as many Vilnans tried to burn down the Reformats church. During the fight at least one protestant was killed, one student was shot in the leg, and both conflicting sides had many injured.

Learn more about the Easter Tumult of 1599 in Vilnius - by clicking this link.

Address: A. Volano St. 2

Vilnius University

The Bishop of Vilnius Walerian Protasewicz (1504-1579) invited the Jesuits to come to Vilnius in 1569. The bishop hoped that the Jesuit order would help to fight against the rapidly spreading ideas of the Reformation among Vilnans. The Jesuits began to carry out their mission without waiting. In 1570, they founded the first college in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. In 1579, king Stephen Báthory (1533-1586) issued a privilege for establishing Vilnius Academy. In the same year, Pope Gregory XIII (1502-1585) granted a bull, confirming the establishment of the University in Vilnius.

The first rector of the University became Piotr Skarga (1536–1612). In the beginning, Vilnius academy had three divisions: humanities, theology, and philosophy. In 1641, the Faculties of Law, and Medicine were established. In the 18th century, natural sciences had been flourishing at the University: in 1753 one of the first observatories in Europe was opened, and in 1781 botanical garden was established.

In 1773, after the abolition of the Jesuit Order, Vilnius University fell into the hands of the Educational Commission. In 1803, less than a decade later after the Grand Duchy of Lithuania became part of the Russian Empire, the University was renamed into The Imperial University of Vilnius. Due to the active involvement of professorship and students in the 1830-1831 uprising, in 1832 university was closed and only opened its doors in 1919.

Learn more about Piotr Skarga - the first rector of Vilnius University, by clicking this link.

Address: Universiteto St. 3

Vilnius Cathedral

The exact date when the first church was built is unknown. Some archeologists think that the first church was constructed by King Mindaugas for his baptism and coronation. Others associate this church with Franciscans church mentioned in Grand duke's Gediminas letters. However, without a doubt, we can say that the church already stood before the beginning of Christianization of Lithuania (1387) built by Władysław II Jagiełło.

In 1419, Jagiełło's cathedral church burned to the ground. Grand Duke Vytautas the Great rebuilt a more massive, hall-type, Gothic cathedral, built on the example of Frombork church. Vytautas the Great planned to receive a crown and become a king of Lithuania in this sanctuary. However, his death and various circumstances that postponed the coronation, his plans were not destined to come true.

Vytautas the Great was the first ruler that was buried at the Cathedral. During the 15th and 16th centuries, the Vilnius cathedral became a place of eternal rest for many rulers, dukes, bishops, and nobles'. In 1506, King of Poland and Grand duke of Lithuania Alexander Jagiellon, and later wives of Sigismund II Augustus - Elizabeth of Austria and Barbara Radziwiłł were buried here.

The driving force for cathedral reconstructions was various disasters. The cathedral was struck by fire in 1530. In 1534 the reconstruction works began, which took about 25 years. The rebuilt basilica gained a Renaissance architecture look. After the fire of 1610, the church was rebuilt in Baroque style, and two towers appeared on its façade.

In the middle of the 18th century, a famous architect Johann Christoph Glaubitz reconstructed the Cathedral. On September 2, 1769, a storm raging in Vilnius destroyed a corner tower of the Cathedral, which in turn broke through the vaults of the adjoining Chapel of the Blessed Mary. The falling vaults killed six priests. In 1781 Laurynas Gucevičius prepared the project, which gave the Cathedral its current look. The works began in 1783 and were completed in 1801.

Learn more about how the Cathedral gained its Classical look by clicking this link.

Address: Šventaragio St. 1

Gate of Dawn

Of ten city gates, only the Gate of Dawn survived to our days. Throughout the centuries, the gates had many names, what symbolizes the changing function and meaning of the Gate of Dawn to the city.

In 1514 the gate was mentioned as the Medninkai Gate, as it led to Medninkai village. At the end of the 16th century, gates had been called Sharp gates (lat. Porta Acialis; pol. Ostra brama). Some historians associate this name with Ašmena town (Ашмя́ны, Oszmiana), which name derived from Lithuanian word "Ašmuo", which means a sharp blade. Probably, this Lithuanian word was directly translated to Latin and Polish languages. When Lithuanians began to call the gate as Gate of Dawn (lit. Aušros vartai) is unknown.

At the beginning of the 16th century, the gate had many elements that characterize Gothic architecture: small narrow arched openings and sharp upward rising niches. At the end of the 16th century, the gate was reconstructed and gained its current look and forms.

In 1621-1626, the Order of Discalced Carmelites began in the vicinity of the gate. At first Carmelite monastery was built, a little bit later - St. Teresa's Church was completed. In 1671, a chapel was built at the gate, which in turn of 18th and 19th centuries gained its late classicism look.

At the end of the 17th century, the chapel became home to the miraculous icon of The Blessed Virgin Mary Mother of Mercy, which turned the Gates of Dawn into a place of worship, to this day attracting thousands of pilgrims to these gates.

Church of St. Johns

Church of St. Johns is one of the oldest Catholic churches in Vilnius. It is believed that the construction of the church began in 1386, initiated by the then King of Poland and the Grand Duke of Lithuania Władysław II Jagiełło, and its construction lasted as long as 40 years.

In 1571, St. the Church of St. Johns was handed over to the Jesuits who arrived a few years ago and had already established a college. After the establishment of Vilnius University, the church was frequently used in the studies process as students organized disputes, performances, and defended their theses in this church.

Elements of different architectural styles (Gothic, Renaissance, Baroque, Classicism) can be found in the church. In the 16th century, the church was largely rebuilt in the Renaissance style. At the beginning of the 17th century, a belfry was constructed next to the church, which became the largest structure in Vilnius. After the fires that broke out in 1737 and 1749, the church suffered as the most of the city's buildings. The church was reconstructed by a famous architect Johann Christoph Glaubitz, who gave the church's façade its intricate and wavy forms of late Baroque architecture.

Learn about public examinations at the Church of St. Johns by clicking this link.

Address: Šv. Jono St. 13

Orthodox Church of the Holy Spirit

St. The Spirit Orthodox Church and Monastery were founded on the initiative of the Vilnius Orthodox Brotherhood. In the 16th century, the currents of Reformation and Counter-Reformation also affected the position of the Orthodox Christians. The Brest Union, which took place in 1596, forced the Orthodox Christians to discover new intellectual forms of how to defend their interests.

As a result, in 1589, the Vilnius Orthodox Brotherhood's statute was approved, and the brotherhood began to defend the interests Orthodox-Christians. Just a few years later, a school and a printing house were established, and in 1596 members of the fraternity began to take care of the construction of a new Orthodox church.

The first wooden church was built in 1597. A few years later, a brick belfry was erected next to the church. A wooden church was just a temporal solution, as in 1633, the brotherhood received a privilege from King Vladislav Vaza, allowing them to build a brick church in this place. The construction was completed in 1638.

In 1749, the Orthodox church burned down during the Great Fire, which ravaged the whole city. Its reconstruction was carried out by Johann Christoph Glaubitz (1700-1767). The works were completed in 1753. During the reconstruction, the interior of the church was enriched with reliefs of Baroque ornaments and ornate iconostasis. The Monastery of the Holy Spirit, which consists of three separate buildings, was established in the 17th century.

The remains of the first three Christian martyrs are being kept here. At the beginning of the 19th century, the self-mummified bodies were found in the basement of the Church of the Holy Spirit. Learn more about Vilnius martyrs by clicking this link.

Address: Aušros Vartų St. 10

Carnival in the Streets of Vilnius

Carnivals were a common sight in Europe in the Middle Ages and the Early Modern Period. During that time, the normal order of life changed: good became evil and vice versa. As Lent approached, people celebrated, ate, and raged. The rich disguised themselves as the poor, and the poor as the rich. Pieter Bruegel the Elder left us one of the best illustrations of this age old tradition in his painting “The Fight Between Carnival and Lent.”

Archive books from the Vilnius Council retained a complaint filed by two Jewish Vilnans, Aaron Lewkowicz and Mojżesz Jakubowicz, on 13 February 1673. The document states “In the current year, one thousand six hundred seventy-three, the twelfth day of the month of February, the aforementioned Lord Italians, having undertaken evil council, harmful to poor people, having dressed themselves up in some sort of strange, never-before-seen garb, in turbans, Turkish style, with masks on their faces, contrary to the custom of this city, around ten people, and offering the occasion and incitement to the common people for tumults to the great and unbearable harm of the plaintiff s, driving back and forth several times on two sleighs on German Street, purposefully passing [the entrance to] Jewish Street, seeking a cause and an occasion for a tumult, they ordered their sleigh drivers to beat the Jews with their whips on their faces, their eyes, which they did indeed do.”

The Italians mentioned in the complaint were Bartłomiej Tukan, Józef Bonfili, and Bartłomiej Cynaki, were citizens of Vilnius. Józef Bonfili was married to a local Lutheran, while Bartłomiej Cynaki was the royal secretary and a burgomaster of Vilnius. He would later become the Wójt (or the mayor in current terms) of the city.

Learn more about the attacks on Jews by clicking this link.

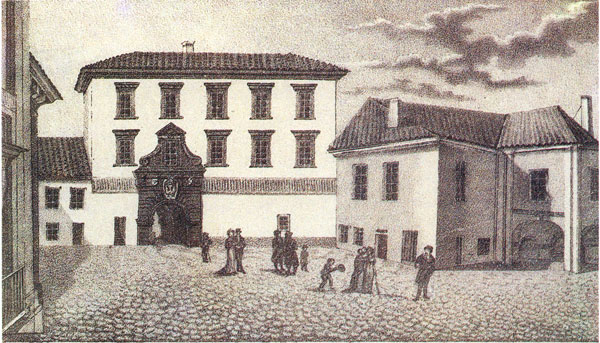

Town Hall

The town hall is the most important center of the political, legal, cultural, and social life of the city. In 1387, King Jagiello granted self-governing Magdeburg rights to the city of Vilnius, which later the rights were expanded by Sigismund Kęstutaitis.

The oldest Town Hall in Vilnius was mentioned in 1432. It stood in the same place as it is now, as evidenced by the surviving Gothic cellars. The Gothic town hall was an elongated two-story building with a one-story annex on the west side. From the middle of the 15th century, a Gothic tower stood next to the town hall, which, like the town hall, was illuminated on public holidays, and musicians played until late at night.

In 1603, the Town Hall was reconstructed. It consisted of several buildings, forming an enclosed courtyard. In 1662, a clock and bell were installed into the Town Hall Tower. The town hall acquired its current classicist appearance after 1788-1799 reconstruction, led by architect Laurynas Gucevičius.

On 8 June 1749, the fire devastated the tower and the Town Hall. Just ten days later, the magistracy signed a contract with a German architect, Johann Christoph Glaubitz (ca. 1715–1767), charging him to rebuild the tower following the city-authorized project. The architect had to procure the materials and hire workers, while the magistracy supplied the copper plates for the spire.

The reconstruction ended in 1769, but eleven years later, in August 1780, the tower barely avoided repeated destruction, once the fire broke out in the neighboring Vokiečių [German] Street. The tower was left unscathed due to the suddenly calmed wind. Despite the happy ending, its days were numbered. Soon after the magistrate realized that the tower was about to collapse, architect Laurynas Gucevičius (1753–1798) suggested straightening the tower and reinforcing its understructure.

Learn more about the tower rescue operation by clicking this link.

Address: Didžioji St. 31

Piotr Skarga courtyard

The Great (Piotr Skarga) courtyard was formed during the Jesuit rule. The northern part of the courtyard is the oldest part of the university. In the second half of the 16th century, this courtyard was called an Academy Yard, later - it was named after Piotr Skarga, who was the first university rector. The courtyard itself consists of buildings from different periods, which in the 17th and 18th centuries acquired features of Baroque architecture. The enclosed courtyard was formed in 1610 when the bell tower was built.

The courtyard galleries contain portraits of the founders, patrons, famous scientists of the university. Among them are portraits of the last king Stanislaus August Poniatowski (1732-1798), King Sigismund Vasa (1566–1632), King August III Saxon (1696–1763).

Learn more about the first rector of Vilnius university by clicking this link.

Address: Universiteto St. 5

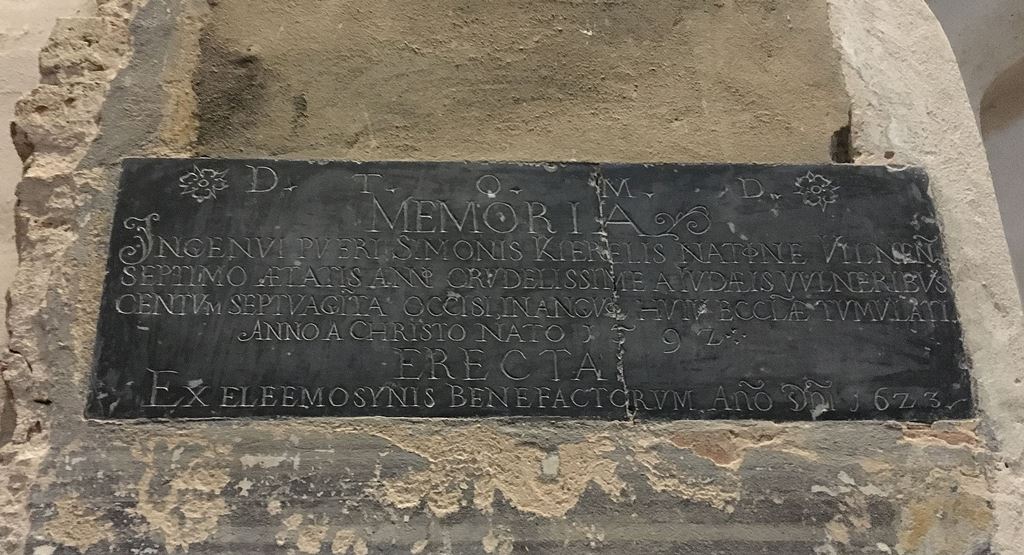

Memorial Plaque to Simonas Kerelis

In Medieval Europe, England and France in particular, many Christians believed that during Pesach, the holiday commemorating the Jewish Exodus from Egypt, Jews re-enact the crucifixion of Christ and use the Christian children’s blood during the ritual.

Jesuit theologian and the first rector of Vilnius University Piotr Skarga introduced the narrative to a broader audience of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. In his book “The Lives of Saints” (1577) he wrote that the Jews tortured Simonas Kerelis, a seven-year-old boy from Vilnius, to death.

Historian Albert Wijuk Kojałowicz also wrote about a boy killed by the Jews in his “Historical Miscelania on the State of the Church in Lithuania” (1650): “Seven-year-old boy of Lithuanian descent, born in Vilnius, was killed in 1592 by the Vilnius Jews, who stabbed him to death with knives and scissors with utmost cruelty. He suffered 170 wounds, moreover, he was tortured by shoving splinters under his fingernails. He was buried in the church of Bernardine fathers in Vilnius. Later on, in 1623, his body was moved to a marble grave outside the church.”

The stories popular in the GDL featured a multitude of harrowing details about the wounds inflicted to the alleged victims. By the late 18th century, much later than in Western Europe, the narrative expanded to include unleavened bread, matzos, that the Jews bake for Pesach – using Christian blood, of course. Later on, even more elaborate versions of the faux story emerged.

Learn more about the Myths of Ritual murder by clicking this link.

Address: Maironio St. 10

Monument to Vilna Gaon

The Vilna Gaon (Elijah Ben Solomon Zalman, 1720–1797) became one of the symbols of the Jewish Vilnius, with countless stories and legends about him, so it is hard to even recognize what are the true facts of his biography and what are not.

A monument to the Vilna Gaon was unveiled in 1997, on the site of a former house where the Vilnius Gaon lived himself. The house that stood here was erected in 1756, when the Jewish community, to improve the living conditions of the Vilnius Gaon, built a small house for his family on Žydų (Jewish) Street, where he lived until his death. A small house of prayer, called in Yiddish "Di gojens kloiz" (Gaon's House of Prayer), was reconstructed next to the house, where he prayed, studied, discussed, and worked with students.

Learn more about the Genius of Vilna by clicking this link.

Address: Žydų St. 3

Vilnius University Library

Vilnius University Library is one of the oldest public buildings in the city that has not changed its purpose to this day. The library was established in 1570 by the Jesuits, who came to Lithuania at the invitation of Bishop Walerian Protasewicz. In 1579 after the reorganization of Vilnius Jesuit College into Vilnius University, the library became a university's library.

The early collections of Vilnius University Library are related to the book collections of Lithuanian rulers. Rulers probably started collecting the books in the Middle Ages, but we can certainly only talk about the books of Sigismund I the Old. Several of them are still stored in the university library. Sigismund II Augustus greatly expanded his father's collection. His agents bought books in various European cities, including Frankfurt, which later became a famous book trade centre. The further growth of the university library was stimulated by donations from the clergy or university students.

The old university library was located in the current Smuglevičius Hall. At that time it had not had such ornate, but it was representative enough. The library moved to the current premises only in the 18th century. The collection of books needed almost a hundred shelves.

Learn more about chained books by clicking this link.

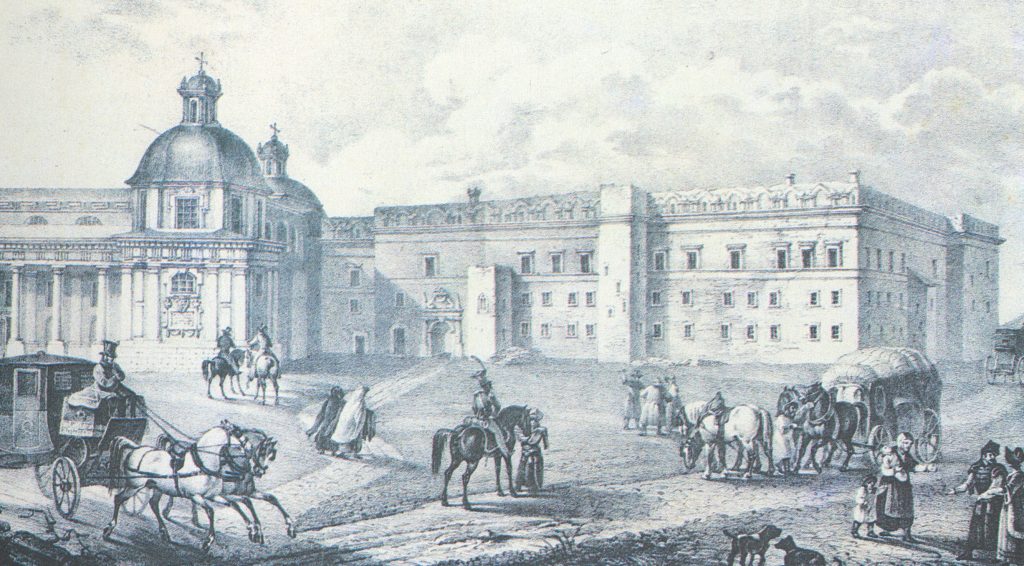

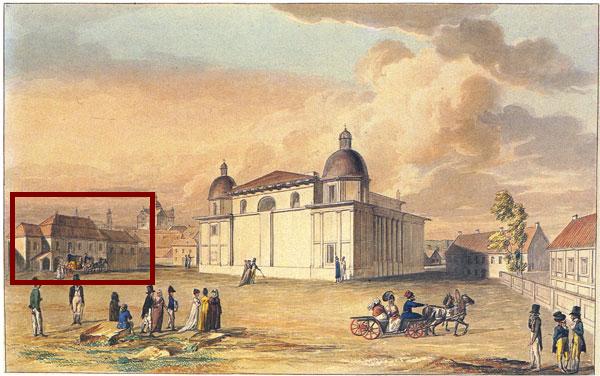

Cathedral Square

The Cathedral Square was formed on the western side of the Lower Castle, south of the Cathedral. On the southern side, the square leaned against the Vilnia river and the Wet gate. The area of the Cathedral square had two owners. The western part of it, including the Cathedral, the old Bishops' Palace, the Cathedral School, and other rented buildings - belonged to the jurisdiction of the Bishop of Vilnius. Meanwhile, the eastern part of the square was under the jurisdiction of the castle, where the main state institutions were established, such as the state treasury, the Supreme Tribunal, the Castle and Land Courts, etc.

The castle's courtyard was a real epicenter of political, commercial, and social life. Nobles, lower-ranking nobles discussed everyday issues, ambassadors of other states revolved here, and it was possible to see the ruler accompanied by a large escort in this area. After the events that happened in the middle of the 17th century, which destroyed the Lower Castle and the surrounding buildings, as well as the most of defensive fortifications, the square gradually became commercial space. The famous Kaziukas fairs gathered a lot of people. Political and social life became more active only during the court sessions of the Supreme Tribunal.

At the end of the 18th century, more and more shopping stools were built in this square, and at the beginning of the 19th century, after the demolition of the Palace of Grand Dukes, the square became primarily a market place. The fairs had been organized here, which attracted merchants from all regions of Lithuania, and even from other neighboring countries. In 1831 the tsar's administration decided to built fortifications in the territory of Vilnius lower castle. During the works, a significant part of the buildings had been demolished, as well as most of the shopping stools. The Cathedral square became an empty place.

The main squares of the cities often became a place of public executions. According to legend, Valentin Potocki, a noble who had converted to Judaism, was burned here in Cathedral square. You can find out more about this legend by clicking this link.

Astronomical Observatory

Haec domus Uraniae est:

Curae procul este profanae!

Temnitur hic humilis telus:

Hinc itur ad astra.

Indeed, from here the human gaze rose towards the stars. Vilnius University Observatory was founded in 1753 and at that time it was then the first observatory in the entire Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and even in the whole continent of Europe. The observatory was established by Tomasz Żebrowski (1714-1758), a Jesuit, astronomer, mathematician, doctor of philosophy, and liberal sciences.

The golden age of the observatory is associated with the rectors of Vilnius University - Marcin Poczobutt (1728-1810) and Jan Sniadecki (1756-1830). The southern annex of the observatory was built in 1782-1788 by architect Marcin Knakfus. Under their rule, numerous important observations of small planets, comets, occultations, and various measurements of geographical coordinates were carried out.

In 1777 Marcin Poczobutt invented a new constellation - "Taureau Royal de Poniatowski" - named in honor of the King of Poland and the Grand Duke of Lithuania Stanislaus August Poniatowski. The new constellation was included almost in all-sky atlases of the late 18th and beginning of the 19th century.

At the end of the 18th century, professors of Vilnius University were renowned because of innovative methods and their application in the sciences. Learn more about how a professor of Vilnius university tamed electricity and used it for treatment by clicking this link.

Address: Universiteto St. 3

Pohulianka

Current day Jono Basanavičiaus Street once had been called "Pohulianka". This street led to the main roads to Trakai and Kaunas. The earliest brick-buildings are mentioned in 16th-century sources. However, till the 19th, this area was mostly covered by gardens. Near the current Pylimo and J. Basanavičiaus St. intersection, the Hilzen palace stood till the end of the 18th century.

There are two versions, which explains the origins of this street name. According to one, this area gained its name from the inn, which stood here. Another version comes from later times, at the end of the 19th century, when first multi-stories high buildings had been constructed, the origins of this Street name was associated with the Russian word "погулять", which means an invitation for a walk.

Address: J. Basanavičiaus St.

Vokiečių (German) Street

As early as the second half of the 14th century, around the current-day Vokiečių (German) Street, a so-called German town, had been established. It is believed, that in the first half of the 15th century, this German town expanded South to the town hall, forming the contours of the current day Vokiečių street.

In the 16th century, this street became one of the main commercial arteries of the city. This is evidenced by the early emergence of brick buildings on this street. As in 1636, all buildings in Vokiečių st. were built from bricks, often two stories high, and richly populated by the Vilnius elites.

In the 19th century, the majority of Vokiečių st. buildings were already three to four storeys high. The street continued to play the role of a commercial center. In 1944 a significant part of Vokiečių Street houses were heavily damaged. After the war, it was decided not to rebuild bombarded houses on the east side of the street. In their place, new buildings emerged, unrecognizably altering the composition of the street.

Address: Vokiečių St.

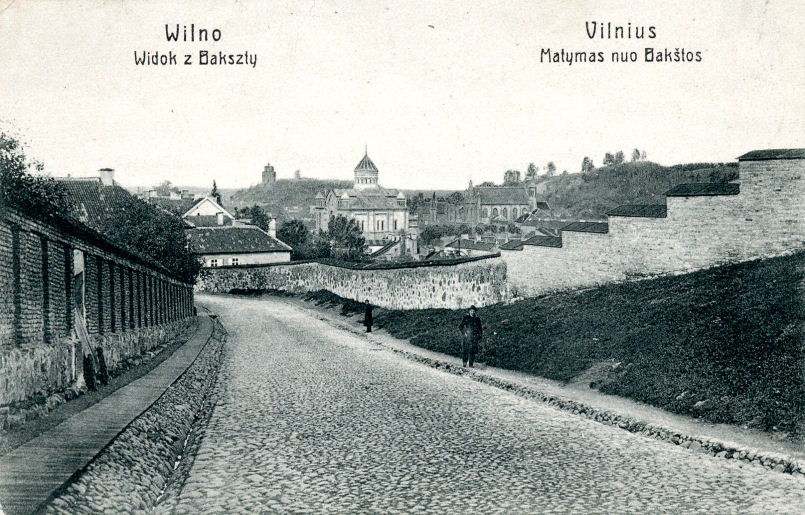

Pylimo Street

The current Pylimo street precisely marks the contours of the once-standing southwestern defensive wall. It is taught that the name of the street originated from the earthen ramparts that were poured here to strengthen the city's defense. Even though almost all former city's defensive structures had been demolished at the beginning of the 19th century, on the east side of Pylimo Street, there are many fragments of the former defensive wall, which were cleverly incorporated in the structures of the adjoining houses.

As archaeological research shows - areas around Pylimo St. were once extremely wet and swampy. At the place where Pylimo and Vingrių streets intersect, there used to be the Vingriai spring, which was the main source of freshwater to all Vilnans. From the 16th century, a cattle market operated behind the Rūdninkai gate.

Address: Pylimo st.

Tilto (Bridge) Street

Tilto (Bridge) Street was used to be called Katedros (Cathedral) Street. Bridge Street formed relatively early. There was never a lack of intense movement on this street as this street lead to an important Ukmergė road, which connected the capital with the Northern part of Lithuania, and an important trade center - Riga.

At the end of the 15th century, here, near the city's defensive fortifications, the ruler's stables and cannon foundry stood. As in the middle of the 16th century, in the territory of the current-day Radvilų, Tilto, T. Vrublevskio streets, the palace of Jerzy Radziwiłł stood.

Address: Tilto St.

Palace of Mikołaj “the Red” Radziwiłł

Since 1544, the territory of the lower castle underwent major construction. In this territory, near the castle hill, Mikołaj "the Red" Radziwiłł's palace was built around 1544. At the same time - a famous underground passage was built, which connected newly built Radziwiłł's residence with the Palace of Grand Dukes. Probably, this passage had been frequently used by King Sigismund Augustus himself to meet his beloved Barbara Radziwiłł.

At that time, Barbara Radziwiłł resided at her brother's palace. The close neighborhood has helped their love grow. Barbara and Sigismund Augustus betrothed some time after June 1545, after the death of the king’s first wife, and since then Barbara lived surrounded by royal splendor. She had her own court, best goldsmiths made her jewellery and top tailors sewed her sumptuous dresses that truly were works of art.

Learn more about a famous love story and how King Sigismund Augustus pampered her with love by clicking this link.

Chapel of St. Hyacinth

Travelers, who went to Trakai, behind the Trakai Gate, since the beginning of the 16th century, were met by a wooden Chapel of St. Hyacinth. In the middle of the 18th century, a 7 meters tall brick chapel was built, which survived to our days. A sculpture of St. Hyacinth did not stand on top of the chapel accidentally, as he is considered the patron saint of travelers and those who are in danger.

Learn more about one trip to Trakai, which ended in the hostage drama, by clicking this link.

Address: Jovaro St. 2

Former Andrzej Morsztyn’s House

On Vokiečių (German) St, in a place of Contemporary Art Centre, once stood a luxurious Andrzej Morsztyn's masonry house. The history of the Lithuanian Reformation names Andrzej Morsztyn as one of the first Vilnan Lutherans.

We know beyond a reasonable doubt that the first Morsztyns moved to Vilnius from Kraków, while their ancestors (Morrinsteins, Mornsteyns, Mornstens, Morstens, etc.) lived in German lands. In the first half of the 16th century, the Morsztyns already showed up among the political and economic elite of Vilnius. Alongside some of the other families, they manage to accumulate power due to their cleverness, wisdom, and riches.

Learn more about the Morsztyn family by clicking this link.

Address: Vokiečių St. 2

Church of St. Raphael the Archangel

In 1697 Jan Kazimierz Sapieha gave the land plot near the right bank of Neris river, called Śnipiszki, to the Jesuit order.

The Church of St. Raphael the Archangel - was built in 1709. The construction of the church was initiated by Michał Koszyc and Michał Kazimierz Radziwiłł. The construction of church towers took many years, as the first tower was completed in 1752, while the second one - was erected in the second half of the 18th century.

The monastery building, which rests on the back of the church, was built in 1730. 1773 after the abolition of the Jesuit order, the monastery was handed over to the Piarist order.

Address: Šnipiškių St. 1

Monument to Kazimierz Siemienowicz

General of artillery and one of the pioneers of rocketry - Kazimierz Siemienowicz (1600-1651) was born in the Raseiniai region in a relatively poor family. However, despite his huge contributions to the science of rocketry, we do not know much about his early life.

It is known that Kazimierz participated in several wars: in 1633-1634 with Russia and 1644 against Tatars. It seems that his talents were acknowledged as the king himself sent him to the Netherlands to gain more knowledge about the art of artillery. In 1646 he returned to the Commonwealth, and from 1648 served as Second in Command of the Polish Royal Artillery.

It seems that the last years of his life had been very productive. In 1650 he published his magnum opus "Artis Magne Artilleriae" and in 1651 - he graduated at Vilnius University.

“The Great Art of Artillery” became a textbook for future artillery and rocketry sciences for the next two centuries. In this great book, a lot of attention was given to the art of producing artificial fires, which at that time were designed by military engineers. Learn more about Baroque fireworks in old Vilnius by clicking this link.

Address: Dariaus ir Girėno St. 21

Pac Palace on Šv. Jonų St.

At the beginning of the 17th century, this building belonged to the goldsmith Stanislaw Zaleski. In 1628, Stefan Pac bought this house, and from then, the Pac family members continuously expanded the palace, which spanned from Šv. Jonų to Švarco Streets. In 1748 the palace was heavily damaged by the great fire that had struck the city.

At the end of the 18th century, the palace changed its owners. In 1783, Aleksander Michał Paweł Sapieha bought the devasted palace and initiated the reconstruction of the palace.

Address: Šv. Jonų St. 3

St. Trinity Church and former Basilian monastery

St. Trinity Church and former Basilian monastery were built on the hill, on which the first three Christian martyrs met their final fate. According to the legends, due to this reason, in 1347, the St. Trinity Church was built on this hill.

The St. Trinity Church, which stands to our days, was built in 1514 under the initiative of Konstanty Ostrogski. Around the same time, the formation of a monastery and church ensemble had started.

In 1607, after the Union of Brest, the monastery was given to the Uniate Basilian brothers, and in 1610 Basilian sisters settled here. After the fire of 1760, the church had been reconstructed by famous architect Johann Christoph Glaubitz. The St. Trinity Church was extended and the towers were built on the western and eastern sides of the church.

Uniate Basilian brothers were expelled from their home in 1821, and Orthodox brothers settled in this complex.

Learn more about the tragic story of three martyrs by clicking this link.

Address: Aušros vartų St. 7b

Pac Palace on Didžioji St.

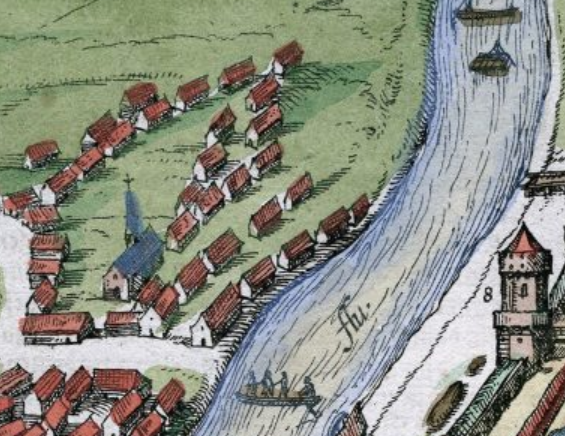

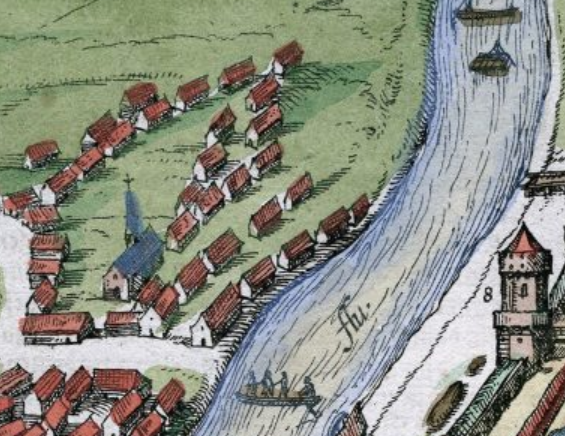

In a place where currently the Pac palace stands, in the 16th century, two houses stood, one of them was called a Vytautas house. According to Braun atlas, this house belonged to Grigalius Astikas, Voivode of Trakai.

In 1667, Michał Kazimierz Pac (1624-1682), the Grand Hetman and Voivode of Vilnius, bought this house. Soon he acquired the nearby house, and in 1673-1677 these two buildings were reconstructed into one. The newly build palace had been one of the most beautiful baroque buildings, decorated by the best sculptors. No wonder that even Jan Sobieski, the king himself, in 1686 during his stay in Vilnius, resided in this palace.

The life of Michał Kazimierz Pac had two sides. On one hand, he was a ferocious and strict warrior, yet on the other hand - he was a generous and pious man.

Learn more about Michał Kazimierz Pac and his outstanding gift to Vilnius by clicking this link.

Address: Didžioji St. 6

Cathedral of the Theotokos

Under the initiative of Maria of Vitebsk, wife of Grand Duke Algirdas, the cathedral of the Theotokos was built in the middle of the 14th century. In 1415, this Orthodox church became the main temple for all Orthodox Christians in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.

At the beginning of the 16th century, a huge disaster struck the church - the dome of the cathedral collapsed, severely damaging the building. Grand Hetman of Lithuania Konstanty Ostrogski (1460-1530) took a lead in reconstructing the main Orthodox temple. Under his initiative, the Cathedral of the Theotokos was rebuilt in 1522.

This cathedral is closely connected with Helena, the daughter of Ivan III. In 1495 Grand Duke Alexander Jagiellon married Helena here Simbollicaly, in 1513, this cathedral became a place of Helena's eternal rest.

Learn more about the abduction of Helena by clicking this link.

Goldsmiths’ Guild

First guilds, which were legally regulated associations of craftsmen, began to establish in Vilnius at the end of the 15th century. In 1495, the goldsmiths' guild was established. The rest of the craftsmen, who did not belong to the guild, could not continue their craft. Each guild had their chappel, members had to celebrate the holidays, and in case if a member gets sick, others had to look after his family.

The house of goldsmiths' guild survived to our days (Gaono St. 6). However, the goldsmiths not only had produced golden jewels for the rich, but they also solved various mysterious cases. One of them was related to the golden boy named Paul. Learn more about this story by clicking on this link.

Address: Gaono St. 6

Radziwiłł Palace in Vilnius St.

The Radziwiłł family owned this plot as early as the beginning of the 16th century. It is known that in this place, just behind the city wall, Mikołaj "the Black" Radziwiłł owned his renaissance style residence, which had been often characterized by Vilnans as one of the most beautiful palaces in the city.

However, the beauty of this palace suffered greatly from the wars in the middle of the 17th and 18th centuries. At the beginning of the 19th century, Dominik Hieronim Radziwiłł donated the former palace to the Vilnius Charity Society.

Without a doubt, during its golden times, this palace had most of the attributes that the ruler's palace had. Entertainment was one of them. In the Late Middle Ages and throughout the Early Modern Period, the most influential magnates followed the popular European trend of hiring jesters and dwarfs. In doing so, they were following the example of the royal court. Learn more about jesters and dwarfs in Vilnius by clicking this link.

Address: Vilniaus St. 22

Shopping Stalls in the Town Hall Square

Trade is an indispensable attribute of any city and the capital of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, Vilnius was no exception. Until the end of the 16th century, it remained one of the most important Eastern European centres for transit trade, while Vilnius-based merchants ranked among the city’s most influential residents.

The Town Hall Square was the main trading area where sellers, including dozens of women, daily displayed barrels of pickled cabbage, bottles of oil, boxes of raw and smoked fish, rolls of cloth, several types of bread, cakes, fresh vegetables, cheese, chicks, geese, and other poultry.

It has to be said that men oversaw all major trading operations. That was the rule without a single exception. The role of women – where, what, and how much they were selling – heavily depended on their individual social status. Small scale trading was the one sector where women truly dominated. Female traders could be as young as their teens and up to well over fifties. Often even very young girls ventured out on the street to earn some money by selling flowers and other goods. Their job was far from safe and children had to be on the lookout against all kinds of evil.

Learn more about women traders in old Vilnius by clicing this link.

Bernardine Monastery Ensemble

The Church of St. Francis and St. Bernard, along with the Church of St. Anne, forms the most impressive ensemble of gothic architecture in all current-day Lithuania. In 1469 the king Casimir IV Jagiellon invited Franciscans observants (called Bernardines) to settle them in Vilnius and donated a plot of land near the Vilnia River.

The first Bernardine church was built from wood, as the current one was built in 1516. According to the contemporaries of that time, the Bernardine and St. Anne churches stood out from the rest city's churches. The place of the church automatically determined the church becoming an integral part of the defense, shielding the eastern part of the city from the potential enemy. Due to this reason, the church has shooting holes in its towers.

Bernardine Monastery in Vilnius, a fortified complex surrounded by walls fitted with shooting holes and towers, became a place where Helena of Moscow, the wife of King Alexander Jagiellon, kept her treasures.

Learn more about Helena of Moscow and her treasures by clicking this link.

Address: Maironio St. 8

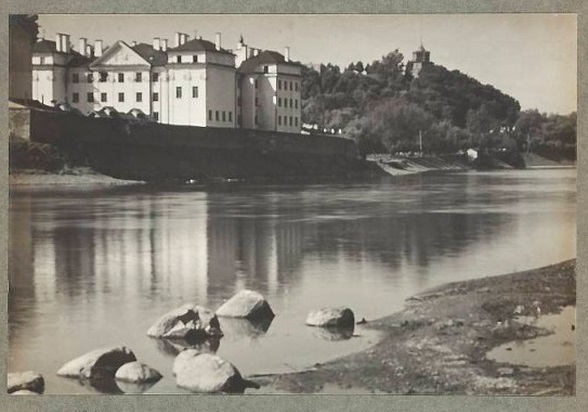

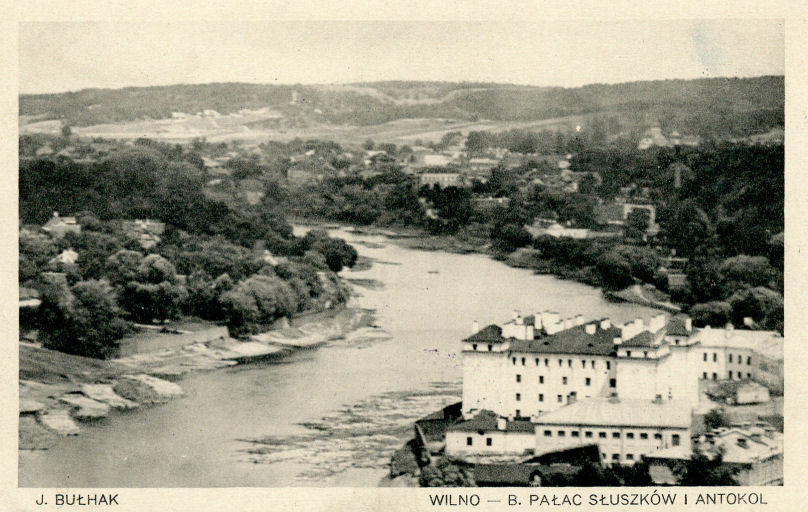

Sapieha Palace in Antakalnis

In 1692, Grand Hetman of Lithuania Jan Kazimierz Sapieha (1637–1720) built one of the most impressive palaces at that time in the hilly outskirts of the city, called Antakalnis. The Sapieha Palace had been built following all Baroque architecture principles of that time. Without hiding his ambitions to become the King of Poland and the Grand Duke of Lithuania, Jan Kazimierz Sapieha built this palace to show others that his family is wealthy and suitable enough for such duties.

The Sapieha palace was not the first building, which stood in this place. At the beginning of the 17th century, a royal architect and horodniczy of Vilnius Peter Nonhart owned a brick house in the plot. Later, the palace belonged to the Naruszewicz, Tiszkewicz, and Pac family members.

The Sapieha Palace was designed by an Italian architect Giovanni Battista Frediani, while decorations and frescoes were created by Italians Giovanni Pietro Perti and Michelangelo Palloni. The palace has two floors, symmetrical-shaped façade. The semicircular pediment was the main accent of the building's façade. The interior of the palace was richly decorated with intricate stucco moldings and frescoes.

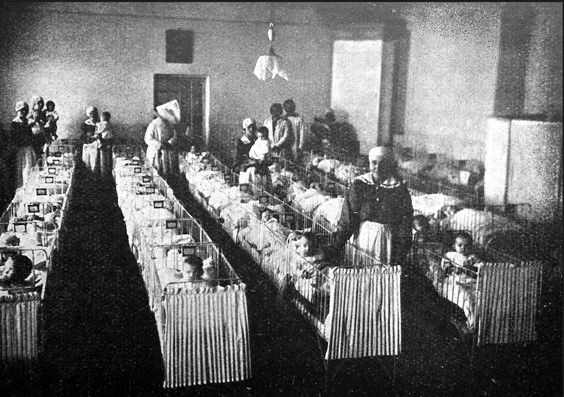

In 1700, after the Battle of Olkieniki, which ended in a defeat of the Sapieha family forces, their ambitions also had vanished. The Sapieha Palace had been devasted by the supporters of the anti-Sapieha coalition after the unuseful battle. Yet till the end of the 18th century, the palace remained in the Sapieha family's hands. Later, the Kozakowski family owned this palace, and in 1808 the tsarist government bought this building and used it as a military hospital.

Address: L. Sapiegos St. 18

Kęsgaila Palace

At the beginning of the 16th century, this plot belonged to the Radziwiłł family. It is possible that during their times, first brick structures were built on this plot. Radziwiłłs owned this plot till 1528 when Stanislaw Kieżgajło inherited this plot from his mother - Hanna Radziwiłł. At the end of the 16th century, the Kęsgaila palace became a property of the Chodkiewicz family, who acquired other nearby plots, later given this complex to The Benedictine sisters. Now only unveiled gothic gates and other elements remind us about the former Kęsgaila Palace.

Address: Šv. Ignoto St. 5

Ogiński Palace

Ogiński Palace formed a separate quarter in Vilnius old town, which consisted of 3 buildings that stretched between Rūdninkų and Arklių streets. The Ogiński family started acquiring these buildings in the middle of the 17th century. The wing of the palace that faces Arklių st. was built at the beginning of the 18th century, while the wing that faces Rūdninkų st. in the middle of the 18th century.

Under the initiative of Ignacy Ogiński (1698-1775), both palace wings acquired their current look. Architect John Hautinga designed an early classical Arklių st. façade. Rūdningų st. the facade was designed by Tom Russell. In the middle of the 19th century, a residential building was built between these two palace wings.

In the second half of the 18th century, numerous grand balls were organized in the Ogiński palace that attracted all the prominent people of the capital. Learn more about the art of hosting a party by clicking this link.

Address: Arklių St. 5

Lopacinski Palace (Skapo St.)

At least from the middle of the 16th century, a brick building stood in place. In the middle of the 18th century, here stood a two stories high palace, which gained its current look after the reconstruction (architect - Marcin Knackfus), which was initiated by the Sulistrowski family, which from 1782 till 1854 owned this building. At the end of the 19th century, the palace was owned by the Lopacinski family.

Address: Skapo St. 4

Lopacinski Palace (Bernardinai St.)

At the beginning of the 17th century in this place, a small brick building stood, which till the middle of 18th century had been vastly expanded, and it was beginning to be called a palace.

In 1762 the new owner of the palace became Mikołaj Tadeusz Łopaciński (1715-1778). Under his initiative, the building was reconstructed by a prominent Baroque architect Johann Christoph Glaubitz ( c. 1700 – 30 March 1767). In 1801, Mikołaj's son Jan Nikodem Łopaciński sold the palace to the Kozakowski family. During the 19th century, the palace belonged to the Olizar and Zawadski families.

Address: Bernardinų St. 8

Gurecki Palace

The Gurecki palace, in the turn of the 17th and 18th centuries, was developed on basis of the pre-existing gothic building. From 1775 till 1790, this building belonged to Walenty Gurecki. Under his initiative, the southern part of the palace was built, forming an enclosed courtyard. At the end of the 18th century, the Gurecki palace gained classicistic architecture features, and the third floor was built.

Address: Dominikonų St. 15

Zawisza Palace

The southern part of Zawisza palace, which faces Dominikonų St., from the end of the 16th till the middle of 18th centuries belonged to the Zawisza family. In 1748, Barbara Franciszka Zawisza, after the death of his husband - Mikołaj Faustyn Radziwiłł, sold this palace to the Treasurer of Trakai Voivodeship - Turczinski.

The part of the palace, which faces Stikliai St., was built in the middle of the 17th century. In the middle of the 18th century, this part of the palace was sold to the Bishop of Vilnius - Michał Jan Zienkowicz.

The palace gained its current look at the end of the 18th century. Durring reconstructions enclosed inner courtyard was formed, southern building's facade gained classicistic features.

Address: Dominikonų St. 13

Pociejai Palace

In the 16th century, in the current place of Pociejai palace, two buildings stood. At the beginning of the 17th century, these two buildings were connected into one.

In the second half of the 17th century, this building belonged to the Woyne family, and at the turn of the 18th century, the building was beginning to be called a palace.

At the beginning of the 18th century, Teresa Wojna (Brzostowska) inherited the palace. She married Aleksander Pociej, Voivode of Trakai, in 1720. Durring the 18th century, the building was reconstructed several times and expanded. In 19th century, the palace became the property of the Umiastowski family.

Address: Dominikonų St. 11

Tyszkiewicz Palace

It is known that at the beginning of the 17th century, a house of craftsmen stood in this plot. The current building stood as early as 1737, it belonged to the Tyszkiewicz family. From 1761 the palace changed its owners as it became a property of the Karp family. Under their initiative, in 1783, the building had been reconstructed by Laurynas Gucevičius. At the end of the 18th century, the palace returned to the Tyszkiewicz family's hands. In 1840, a balcony was built, which was held by two Atlases.

Address: Trakų St. 1

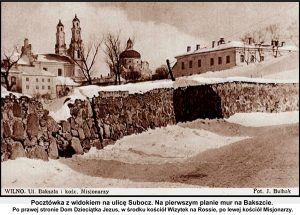

Bastion of Vilnius

In the first half of the 17th century, a need to reinforce town's defensive measures, a bastion was built in the wall next to Subačiaus Gate. It was a defensive structure consisting of a tower, a horseshoe-shaped part meant for the artillery, and a connecting tunnel.

The bastion suffered greatly in 1655–1661 during the war with Russia. Although it was rebuilt, the bastion gradually lost its function and fell into decay. As a result, in the late 18th century, the bastion territory was turned into a city dump, its moats and walls were covered with earth.

Address: Bokšto St. 20

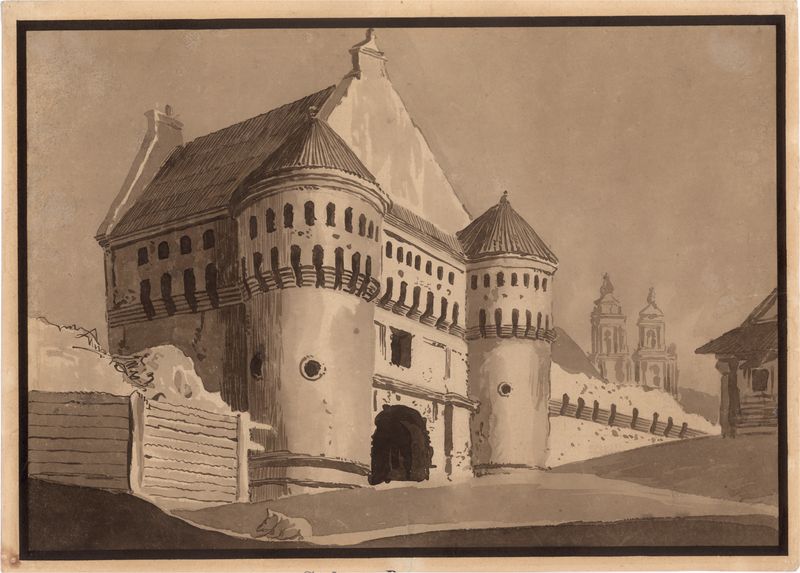

Bernardine Gate

In 1503 King Alexander Jagiellon granted a privilege to the residents of Vilnius to fortify the city with a defensive wall to repel the potential attackers, as at the beginning of the 16th century, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania was facing a growing military threat from Muscovites and Crimean Tatars. According to the privilege, the wall should feature five gates - all leading to the most important cities. However, in the middle of the 17th century, the city of Vilnius had 10 gates.

The tower of Bernardine gate stood next to the bridge that leads to Užupis, a little bit to the south from St. Anne church. The gate had not played a significant role in the town's defense, as nearby Bernardine church and hills formed relatively good protection from the enemy. The gate served more as a representative role, richly decorated with volutes and pilasters, it greeted incoming travelers.

Address: Maironio St. 11

Spas (Saviour) Gate

In 1503 King Alexander Jagiellon granted a privilege to the residents of Vilnius to fortify the city with a defensive wall to repel the potential attackers, as at the beginning of the 16th century, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania was facing a growing military threat from Muscovites and Crimean Tatars. According to the privilege, the wall should feature five gates - all leading to the most important cities. However, in the middle of the 17th century, the city of Vilnius had 10 gates.

The Spas gate was mentioned in the 1503 privilege. However, the exact date when the gate was built is unknown, just as we do not know how the gate looked like. According to the various sources of the 17th century, the gate was characterized as magnificent and gorgeous. The Spas gate was demolished in 1801.

Subačius Gate

In 1503 King Alexander Jagiellon granted a privilege to the residents of Vilnius to fortify the city with a defensive wall to repel the potential attackers, as at the beginning of the 16th century, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania was facing a growing military threat from Muscovites and Crimean Tatars. According to the privilege, the wall should feature five gates - all leading to the most important cities. However, in the middle of the 17th century, the city of Vilnius had 10 gates.

Subačiaus gate was built at the beginning of the 16th century. It was one of the most important gates of the town, leading to the towns of Polock, Smolensk, and Moscow. The Subačius gate was four stories high, protruded outside the city wall. Gate tower was used not only for defensive reasons and had heated living space inside it, where the city's executioner lived. The Subačius gate had been demolished in 1801.

Learn more about executioners of Vilnius by clicking on this link.

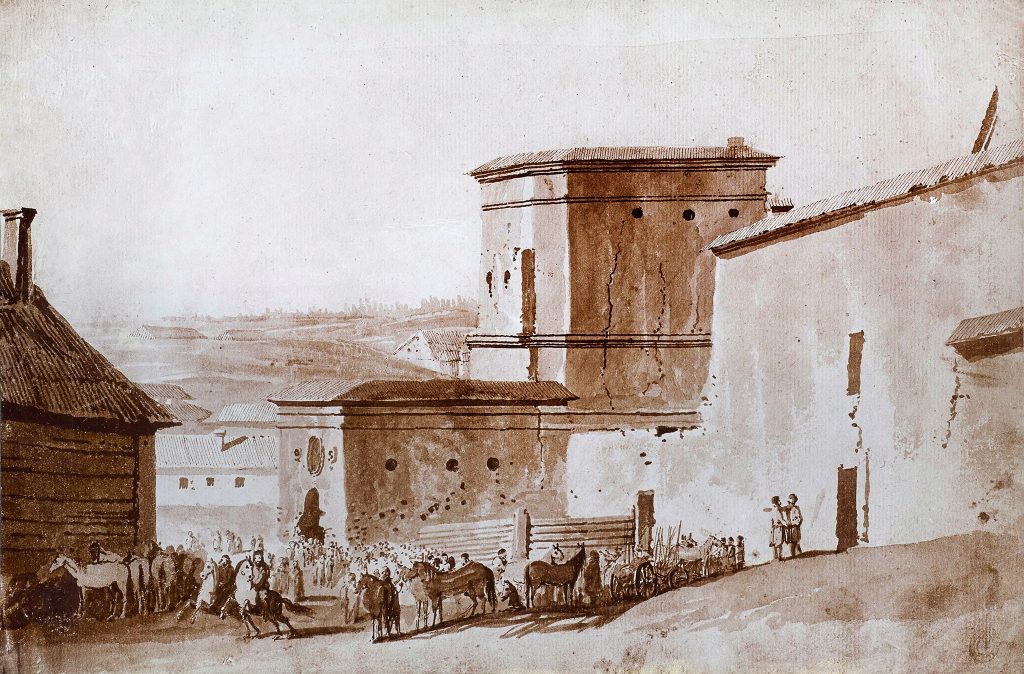

Rūdninkai Gate

In 1503 King Alexander Jagiellon granted a privilege to the residents of Vilnius to fortify the city with a defensive wall to repel the potential attackers, as at the beginning of the 16th century, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania was facing a growing military threat from Muscovites and Crimean Tatars. According to the privilege, the wall should feature five gates - all leading to the most important cities. However, in the middle of the 17th century, the city of Vilnius had 10 gates.

The construction of the Rūdninkai gate was completed around 1522. The road behind the gate led to Grodno and further to the most important towns of Poland. The gate was well designed defensively: it had two gates to trap the enemy, and shooting holes to attack the incoming enemy from the distance. The gate was demolished in 1800.

Closure of all city gates at sunset became a ritual marking the beginning of the night. To defend the town from wandering danger many night guards suffered injuries and even was deprived of his life at their hands. The areas outside the city proper were very dangerous, even the most courageous rarely ventured beyond the gates. Learn more about the Old Vilnius after nightfall by clicking this link.

Address: Pylimo St. 46

Trakai Gate

In 1503 King Alexander Jagiellon granted a privilege to the residents of Vilnius to fortify the city with a defensive wall to repel the potential attackers, as at the beginning of the 16th century, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania was facing a growing military threat from Muscovites and Crimean Tatars. According to the privilege, the wall should feature five gates - all leading to the most important cities. However, in the middle of the 17th century, the city of Vilnius had 10 gates.

Trakai gate was mentioned in 1503 privilege. In the second half of the 18th century, the gates tower had 2 floors, its architecture had baroque features From the city side, above the gate, a picture of St. Mary hung, which in 1803, after the demolition of the gate, was moved to the nearby Franciscan church.

Address: Trakai St. 2

Vilija Gate

In 1503 King Alexander Jagiellon granted a privilege to the residents of Vilnius to fortify the city with a defensive wall to repel the potential attackers, as at the beginning of the 16th century, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania was facing a growing military threat from Muscovites and Crimean Tatars. According to the privilege, the wall should feature five gates - all leading to the most important cities. However, in the middle of the 17th century, the city of Vilnius had 10 gates.

In 1503 King Alexander Jagiellon granted a privilege to the residents of Vilnius to fortify the city with a defensive wall to repel the potential attackers, as at the beginning of the 16th century, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania was facing a growing military threat from Muscovites and Crimean Tatars. According to the privilege, the wall should feature five gates - all leading to the most important cities. However, in the middle of the 17th century, the city of Vilnius had - 10 gates.

Vilija (also called Vilnius) gate was mentioned in 1503 privilege. Yet, we do not know whether the Vilija gate was initially built as historical sources mention them only from the middle of the 16th century. The gates stood where now Benediktinų St. meets Vilniaus St.

The gate was well designed defensively, had sliding gates and shooting holes. The painting of the Virgin Mary met the travelers who entered the city through this gate. In 1802, after the destruction of the gate, the painting was moved to the Chapel of children orphanage in Subačiaus St.

Address: Vilniaus St. 37

Tatar Gate

In 1503 King Alexander Jagiellon granted a privilege to the residents of Vilnius to fortify the city with a defensive wall to repel the potential attackers, as at the beginning of the 16th century, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania was facing a growing military threat from Muscovites and Crimean Tatars. According to the privilege, the wall should feature five gates - all leading to the most important cities. However, in the middle of the 17th century, the city of Vilnius had 10 gates.

How the Tatar gate looked like is unknown. Painter Juozas Kamarauskas portrayed the gates after 90 years when the gates were demolished. It is believed that the gate was built at the end of the 16th century. According to different sources, the gate tower was 3 storeys high. The tower stood near the Vingriai-Kačerga stream.

Learn more about why the Tatar gate was called Tatar by clicking this link.

Address: Totorių St. 2

Slushko Palace

The place where now the Slushko palace stands had been popular among nobles from the beginning of the 16th century as many of them built their residences near the shore of Neris. At the end of the 16th century, the Kiszka family built their residence, which in the middle of the 17th century belonged to the Pac family.

In 1690 Pac sold the palace to Dominik Slushko (1655-1713). The palace, which stood on the shore of Neris river, seems to be not impressive enough, as the new owner decided to tear it down and built a new residence in this place, a little bit closer to the Neris river. It seems that at the beginning of the 18th century, the Slushko palace was one of the most beautiful residences in Vilnius, as in 1705, the Russian Empire's army headquarters were stationed in the palace.

Later, throughout the times, the Potocki, Puzyna, and Oginski families owned this residence.

Learn more about the Russian tsar's stay in Vilnius by clicking on this link.

Address: Kosciuškos St. 10

Brzostowski Palace

In the 16th century, this plot belonged to the Bishop's jurisdiction. In 1595, Bishop Benedyckt Woyna (d. 1615) granted a privilege to Jan Dzienicki to built a house in this plot. In 1640 a brick house was built in the southern part of the plot.

Both houses were bought by Cyprian Paweł Brzostowski (1612-1688), who later connected these two buildings into one. In 1760 Paweł Ksawery Brzostowski (1739-1827) inherited the palace. Under his initiative, the palace was reconstructed in 1761 (architect - Marcin Knackfus).

In 1772, the palace was sold to the Nagurski family and later belonged to the Oginski family.

Address: Domininkonų St. 18/2

House of Jan Kluczata

In 1629 King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania Sigismund Vasa issued a privilege that charged him with a somewhat unusual, especially considered from the 21th century perspective, obligation of guarding a part of the state archive, the Lithuanian Metrica.

This privilege is the earliest of its kind, but several others were issued soon after: in April 1636 Jan Kluczata (Didžioji Street 13) and in December of the same year Gregory Kozlanowski (Didžioji Street 11) were charged with guarding the archive.

Learn more about the Lithuanian Metrica in Vilnans houses by clicking on this link.

Address: Didžioji St. 13

Statue of the Lamplighter

After the sunset, darkness enveloped the streets of old Vilnius, unless the skies were clear at a night of full moon. The royal residence in the Lower Castle was the only exception. The first street lamps were installed beside the palace back in the second half of the 16th century. Later on, in the early 1700s, more lamps were set by Vilnelė. Lamplighters employed by the court took care of them.

Across the rest of the city, most windows were pitch dark. Only rich people could afford candles, let alone fireplaces. The city would burst into light during religious and secular holidays, because the Town Hall, main churches, and magnate palaces were illuminated. Gas lighting was first introduced in Vilnius in 1824, just about in time with other cities across Europe and North America.

Many pious residents of Vilnius spoke against the street lights, they insisted that those distort the order set by God according to which nights must be dark. Light, they maintained, encouraged people to drink, sin, commit crimes, and spread diseases.

Learn more about the Old Vilnius after Nightfall by clicking this link.

Address: Šv. Jono St. 8

Pillar of Shame in Vilnius Townhall Square

Whenever justice was to be served in the form of public execution, a wooden platform rose in the Town Hall Square, it was called the theatre. Magicians, murderers, thieves, counterfeiters, and all sorts of criminals ascended it to meet their death.

The mildest punishments were usually carried out at the Pillar of Shame, also known as the ‘pilot’. Made of wood and fitted with iron hooks, it also stood in the Town Hall Square of Vilnius. It was primarily used for whipping, but sometimes the chained offender would lose his or her ear for committing petty crimes, such as minor theft or brawl. Sometimes the punishment was limited to chaining a person to the whipping post for an hour or two. On other occasions the court would adjudge five hundred or even a thousand lashes. Not even the strongest men could survive such beating.

Address: Rotušės Sq.

House of Catherine Giblówna

Cornelius Winhold and Catherine Giblówna, then in their mid-teens, both lived on Castle Street in Vilnius, their homes just a hundred metres apart. Both of them were born in wealthy families. Winhold's father moved to Lithuania from the Netherlands, Catherine's - from Germany.

None can tell when exactly Cornelius and Catherine did fall for each other, but their romance did not last long before facing serious trials. The Winhold family, to provide Cornelius with the best possible education, sent their son on a “pilgrimage through schools”. In 1615, being barely 14 years of age, Cornelius enrolled at the University of Marburg. One year on, he studied in Basel before continuing his education in the universities of Amsterdam (in the summer of 1620) and Paris (in the spring of 1621).

Cornelius did not forget Catherine. He sent her many letters, but only two messages to his cousin have survived to our day. In the spring of 1621, Cornelius received news that Catherine was going to be married to the other man. Cornelius returned to Vilnius and next year, in 1622, married his beloved Catherine.

Cornelius and Catherine lived in the Winhold house on Castle Street 20. Judging by its surviving inventory, they had everything the beginning of the 17th century could offer: a separate kitchen, rooms for servants, storage areas, cellars for food and wine, windows of Venetian glass, and even running water.

Learn more about this love story by clicking on this link.

Address: Pilies St. 13

Gambina’s Pharmacy

Only two or three pharmacies operated in the early 16th-century Vilnius, but that completely sufficed, as the city was fairly small with the population not exceeding 30,000 inhabitants.

Every pharmacist was able to distil all kinds of alcoholic beverages, such as vodka, nalewka, and strongly aromatised liqueurs. That’s when he required an alembic, a distillation apparatus present in every pharmacy. Some called it the king of the Renaissance pharmacy.

In pursuit of larger profits and greater prestige, they settled their businesses exclusively in the centre of the city, in the vicinity of the Lower Castle, and on the present-day Vilnius street, later - in the Pilies, Didžioji, and Vokiečių streets. Several buildings have survived where pharmacies operated in the 16th century: Didžioji St. 6 (Jablka’s), Didžioji St. 8 (Gambina’s), and Pilies St. 20 (Rupert Fink’s).

To learn more about pharmacies and medicine in old Vilnius by clicking on this link.

Address: Didžioji St. 8

Jakub Jabłek’s Pharmacy

Only two or three pharmacies operated in the early 16th-century Vilnius, but that completely sufficed, as the city was fairly small with the population not exceeding 30,000 inhabitants.

Every pharmacist was able to distil all kinds of alcoholic beverages, such as vodka, nalewka, and strongly aromatised liqueurs. That’s when he required an alembic, a distillation apparatus present in every pharmacy. Some called it the king of the Renaissance pharmacy.

In pursuit of larger profits and greater prestige, they settled their businesses exclusively in the centre of the city, in the vicinity of the Lower Castle, and on the present-day Vilnius street, later - in the Pilies, Didžioji, and Vokiečių streets. Several buildings have survived where pharmacies operated in the 16th century: Didžioji St. 6 (Jablka’s), Didžioji St. 8 (Gambina’s), and Pilies St. 20 (Rupert Fink’s).

To learn more about pharmacies and medicine in old Vilnius by clicking on this link.

Address: Didžioji St. 6

The City Gatekeeper

History of night differs from that of day. Many societies regarded darkness with fear and the night as the time of evil forces and the devil. The night makes some people feel uneasy, others suffer from nyctophobia, an extreme fear of night or darkness. On the other hand, it serves as a symbol of divine mystery and a source of inspiration for poetic souls.

In the 16th century, when a defensive wall was built around Vilnius, closing of all city gates at sunset became another ritual marking the beginning of the night. This was a precaution taken to secure the city, while the citizens had to guard their persons and possessions themselves.

Hired watchmen guarded the peace at night. They were joined by merchants and artisans, who were obliged to patrol at night. The job was very dangerous, because dozens of criminals and drunkards roamed the streets. Inebriated gun or sword-bearing nobles often caused a ruckus. Many night guards suffered injuries or even lost their lives guarding the city. The areas outside the city proper were very dangerous, even the most courageous rarely ventured beyond the gates.

This sculpture was created in 1973 by Stanislovas Kuzma.

Learn more about the Old Vilnius after Nightfall by clicking this link.

Former Belfry of the Franciscan Church

From the end of the 16th century until 1872, the Gothic belfry stood in current day Pranciškonų St., which housed the Ciechanovicz Bell, named after the Franciscan friar who had funded its casting in the 17th century.

There were two reasons why belfry had been demolished. One was the active involvement of the Franciscans in the 1863-1864 Uprising against the Russian rule. Another was that a gothic belfry restricted movement on city streets.

Learn more about Franciscan Friary by clicking on this link.

Address: Pranciškonų St. 1

Gallows Hill

The executions were made public to deter people from criminal behaviour. The practice of public punishment was well alive until the late 18th century, when the punishments and the details of their enactment were announced in the local newspapers.

Just like other larger cities, Vilnius was a place where all kinds of criminal activity occurred. Individual lawbreakers, local criminal gangs, and, occasionally, travelling thieves, burglars, crooks, and other felons paved its streets.

Just like in many other European cities, the gallows stood beyond the city wall. The area next to the Gate of Dawn, known as the gallows or the Franciscan hill, was owned by the Franciscan monks who collected annual fees from the city for the use of their land.

Learn more about crimes and punishments in old Vilnius by clicking on this link.

Address: V. Šopeno St.

Glasshouse near the Green Bridge

The decisions Lithuanian rulers made several centuries ago would raise a few eyebrows today. One of such decisions was handing over the right to practice a trade to a single artisan, effectively making him a monopolist. This is exactly what happened in the 16th century Vilnius when the right to manufacture glass was limited to one person.

The lucky man’s name was Marcin Palecki. In 1547 King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania Sigismund Augustus granted the privilege making him the only legal producer, importer, and trader of glass in Vilnius.

However, it appears that Marcin was not the first Vilnan who produced and sold glass. Recent discoveries show that Marcin was following in the footsteps of his father Jan, who took over the glass trade from his namesake bishop of Vilnius in 1525. New discoveries show that Bishop Jan was a businessman in a cassock and established the glasshouse in 1519, dating the start of glass making in Vilnius no less than three decades earlier than previously believed.

The glasshouse stood on the bishop’s private land outside the city walls, near the present-day Green Bridge, then known as the Grand Bridge. Six years later, on 4 November 1525, the bishop sold it to “the Polish glass maker” Jan Palecki.

Learn more about glassmaking traditions in Vilnius by clicking this link.

Place of the Royal Kennel

In the 16th-century Vilnius, the Palace of the Grand Dukes of Lithuania echoed with a multitude of sounds that included the barking, whining and growling of dogs. The Grand Dukes of Lithuania and their family members owned canines of various breeds, ranging from small puppies to exceptional hunting dogs.

The largest packs of dogs, of up to two hundred Hounds and Greyhounds, were kept well outside the Palace of the Grand Dukes, in the royal kennels. The first ones were located well outside the city, in what is today Valakampiai, beside the then summer residence of the ruler. By 1553 they were moved closer and occupied the area between the present-day Green and Mindaugas Bridges. At the time the royal kennels shared the space on the right side of River Neris with fishermen’s houses, a brickyard and a glass workshop. The kennels employed dozens of servants of different ranks, all taking care of the dogs. Some dog keepers were meant to train them, others took them hunting, or fed them.

Learn more about the royal dogs in Vilnius by clicking on this link.

Address: Žvejų St.

House of Jakub Mora

Jakub Mora was a rich goldsmith. He lived in a luxurious house in the heart of Vilnius in what today is Didžioji Street no. 19. In 1629 King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania Sigismund Vasa issued a privilege that charged him with a somewhat unusual, especially considered from the 21st-century perspective, the obligation of guarding a part of the state archive, the Lithuanian Metrica.

This privilege is the earliest of its kind, but several others were issued soon after: in April 1636 Jan Kluczata (Didžioji Street 13) and in December of the same year Gregory Kozlanowski (Didžioji Street 11) were charged with guarding the archive.

Learn more about the Lithuanian Metrica in Vilnans houses by clicking on this link.

Address: Didžioji St. 19

Rupert Fink’s Pharmacy

Only two or three pharmacies operated in the early 16th-century Vilnius, but that completely sufficed, as the city was fairly small with the population not exceeding 30,000 inhabitants.

Every pharmacist was able to distil all kinds of alcoholic beverages, such as vodka, nalewka, and strongly aromatised liqueurs. That’s when he required an alembic, a distillation apparatus present in every pharmacy. Some called it the king of the Renaissance pharmacy.

In pursuit of larger profits and greater prestige, they settled their businesses exclusively in the centre of the city, in the vicinity of the Lower Castle, and on the present-day Vilnius street, later - in the Pilies, Didžioji, and Vokiečių streets. Several buildings have survived where pharmacies operated in the 16th century: Didžioji St. 6 (Jablka’s), Didžioji St. 8 (Gambina’s), and Pilies St. 20 (Rupert Fink’s).

Rupert Fink's pharmacy in the second half of the 16th century was one of the biggest pharmacies in the city. He was a royal physician, who came from Germany

There are several famous stories related to Rupert Fink. To learn more about pharmacies and a famous pharmacist Ruper Fink by clicking on this link.

Address: Pilies St. 20

Klukowski’s Café

Widely known and loved in the Muslim world since the 15th century, coffee was not popular in Europe until the 1600s. After the Battle of Khotyn (1673) against the Ottomans in today’s Ukraine, the commanders of the Lithuanian army are believed to have brought some Turkish coffee back to Vilnius. Indeed, there are more legends linking war, Turks, and coffee. In 1683, after the Battle of Vienna when the legendary Hussar army sealed the outcome of the battle, an unknown soldier is said to have found as many as 300 bags of coffee among the Ottoman supplies. He took them and opened a café in Vienna.

Yet it took more time for Vilnans to become fascinated by the smell of roasted coffee beans. The first illegal café was operated at least in 1787, when neighbors filed a complaint to a local court of law against Simon and Barbara Klukowski who had fitted an illegal signboard to the house to advertise the coffee they were selling. The Klukowski House, now number 5 or 7 on St John’s Street, is where, quite likely, Vilnius’ earliest café was.

Learn more about coffee culture in old Vilnius by clicking on this link.

Address: Šv. Jonų str. 5/7

The Wet Gate

In the early 16th century, when the Grand Duchy of Lithuania was facing a growing military threat from Muscovites and Crimean Tatars, King Alexander Jagiellon granted residents of Vilnius a royal privilege to fortify the city with a defensive wall to repel the potential attackers.

According to the privilege, the wall should feature five gates, all leading to the most important cities. However, this plan was altered in accordance with the demands of everyday life. The Wet Gate or the Gate of Mary Magdalene had no turrets, no defensive features, and looked much more like a simple hole in the wall, as it was built for a local residents to easier access the western suburbs of the city.

According to archaeologists who had spent years examining the remains of the city wall, the Wet Gate stood where nowadays Grand Hotel Kempinski meets the former De Reus Palace (Universiteto St. 10), next to the Presidential Palace. Its history is fairly short. Built sometime in the middle of the 16th century, the Wet Gate was walled up in 1677, when the Vilnius magistrate decided to fortify the weakest links in the wall. It remained unused until the early 19th century when the Russian tsar ordered an almost complete destruction of the wall.

Learn more about the history of the Wet Gate of Vilnius by clicking on this link.

House of Cornelius Winhold

Cornelius Winhold and Catherine Giblówna, then in their mid-teens, both lived on Castle Street in Vilnius, their homes just a hundred metres apart. Both of them were born in wealthy families. Winhold's father moved to Lithuania from the Netherlands, Catherine's - from Germany.

None can tell when exactly Cornelius and Catherine did fall for each other, but their romance did not last long before facing serious trials. The Winhold family, to provide Cornelius with the best possible education, sent their son on a “pilgrimage through schools”. In 1615, being barely 14 years of age, Cornelius enrolled at the University of Marburg. One year on, he studied in Basel before continuing his education in the universities of Amsterdam (in the summer of 1620) and Paris (in the spring of 1621).

Cornelius did not forget Catherine. He sent her many letters, but only two messages to his cousin have survived to our day. In the spring of 1621, Cornelius received news that Catherine was going to be married to the other man. Cornelius returned to Vilnius and next year, in 1622, married his beloved Catherine.

Cornelius and Catherine lived in the Winhold house on Castle Street 20. Judging by its surviving inventory, they had everything the beginning of the 17th century could offer: a separate kitchen, rooms for servants, storage areas, cellars for food and wine, windows of Venetian glass, and even running water.

Learn more about this love story by clicking on this link.

Address: Pilies str. 20

Church of St. Peter and St. Paul

This architectural gem of the city, dedicated to Saints Peter and Paul, surpassed its time by interior decoration, art historians claim. Fortunately for Vilnans and visitors of the city, the church is in an almost impeccable condition today, more than three centuries from the day when its founding stones were laid in 1668.

The Church of St. Peter and St. Paul was the first one to be built of stone outside the city walls. Until then, only wooden churches had been built on the outskirts of the capital. In other words, Pac chose a secluded corner of suburbs for a huge investment rather than a prestigious location in the city centre.

Next to the church, a spacious monastery for the Canons Regular of the Lateran was erected. Interestingly, at the beginning of its construction, the old wooden monastery housed no more than ten monks who lived there permanently. However, the most impressive part of this church is its interior, which has over three thousand white statues and figurines.

Learn more about the precious gem of Vilnius by clicking more on this link.

Address: Antakalnio str. 1

Bekes Hill

While listing famous foreigners of old Vilnius, one should reserve an entry for Hungarian nobleman and talented military commander Gáspár Bekes (1520–1579). Born and bred in the border region between present-day Hungary and Romania, although he has visited Vilnius just twice, the city of Vilnius became his final resting place and still keeps his memory, as one of the central hills bears his name.