Gediminas, the Ingenious Ruler of Pagan Lithuania

In the shadow of Egyptian pyramids, ascetics began to gather since the 3rd century AD. Hundreds of pious men would retreat into the desert and devote themselves to the search for God. This was the beginning of Christian monasticism, the movement that soon spread across the various parts of the old world, throughout Africa, Asia, and Europe. St Anthony the Great was probably the most famous Christian ascetic.

Once, several Greek philosophers decided to visit St Anthony, a man of no formal education, and overwhelm him with true wisdom. However, it was the learned men who were the ones overwhelmed by his seemingly simplistic reasoning. He asked them: what comes first, mind or scripture? Naturally, the philosophers opted for the mind. And then St Anthony retorted: if so, then a man of common sense can do without writing.

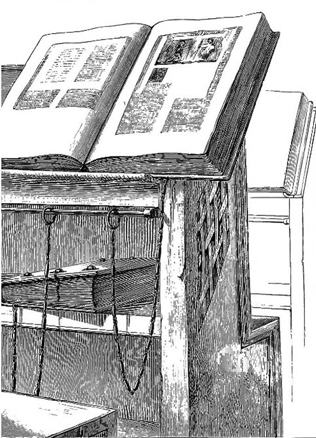

Letters of the illiterate monarch

Quite possibly, the papal legates felt similarly embarrassed in the late autumn of 1324 on their way back to Riga from Vilnius, where they met Gediminas, an illiterate pagan Lithuanian ruler.

“

The famous letters of Gediminas, written in 1322-1323, attracted great interest throughout Europe. Many hoped that Gediminas would at last be baptized and bring Lithuania into the family of Christian nations of Europe.

The famous letters of Gediminas, written in 1322-1323, attracted great interest throughout Europe. Many hoped that Gediminas would at last be baptized and bring Lithuania into the family of Christian nations of Europe.

In his letters, Gediminas had made some truly enticing promises. “We open our lands, possessions, and the kingdom to every man of good will: knights, squires, merchants, peasants, blacksmiths, wheelers, shoe-makers, furriers, millers, tavern keepers, and every craftsman. We want to give our land to all these listed, each according to his rank. Those who wished to come as farmers, let them work the land free of tax for ten years. Let the Merchants enter and leave free of tax and customs and without any hindrance. Let the common people enjoy the civil rights of the city of Riga unless, after consulting the learned, we invent something.”

Do You Know?

To the settling farmers, Gediminas promised, that come the time to pay the tithe, they would retain more fruits of their toil than in other European countries. The letters of Gediminas was the first promotion campaign of living in Lithuania.

The promises were meant to sound reliable: “Our word is as strong as steel”, “the iron will sooner turn into wax and the water will change into steel than we will take our word back.”

The main message was the intention to adopt Christianity

Settlers, Gediminas promised among other things, will be granted the freedom to profess their Christian faith. He also mentioned the churches that are already built for merchants in Vilnius and Navahrudak. Announced that these are ministered by the Franciscans who dispose of “complete freedom to baptize, preach, and perform other sacred services.” The key to this new and wonderful world is hidden in the heart of the “king of Lithuanians and many Ruthenians.” “Only God and I know what’s in my heart,” Gediminas wrote.

“

On several occasions, he insinuated that he was determined to adopt Christianity.

On several occasions, he insinuated that he was determined to adopt Christianity.

In a letter to all Christians, he stated: “We have sent our envoy with our letter to the Apostolic Lord and our Holy Father concerning the acceptance of the Catholic faith. We know his answer and we expect his legates every day impatiently.”

In a letter to the Dominicans he said: “We have sent envoys with a letter to our Most Glorious Father, Pope John, so that he dressed us in the best robes, and we look forward to His messengers daily with great fear and impatience, for with the approval of the Lord Jesus Christ we will be ready to fulfill his will whatever it might be.”

“

More than once, Gediminas noted that he was looking forward to the baptism plan being implemented as soon as possible.

To the Franciscans, Gediminas fashioned himself as a sheep looked after by the pope: “We want you to know that we have sent our letter to our Father, the noblest lord John […], who will lead us to the fertile pasture together with his other sheep.”

Gediminas was frank when addressing the inhabitants of German cities: “We have sent a letter to the Pope with regard to joining the Church of God.”

More than once, Gediminas noted that he was looking forward to the baptism plan being implemented as soon as possible.

Papal envoys in Vilnius

After a while, Pope John was eventually persuaded that Gediminas did mean what he wrote. He appointed a benedictine monk and the bishop of Alet-les-Bains Bartholomew and the abbot of St Theofred monastery of the diocese of Annecy Bernard, as his legates, “men especially gifted with the knowledge of the scripture, of laudable life and bearing a divine gift of interpreting the gospel.”

They were far from naïve, so after arriving in Riga in the autumn of 1324, they sent their representatives to Vilnius to assess the situation. Once their agents arrived, they learned from a local Dominican monk Nicholas that “the king’s idea has changed so that he does not want to accept the faith of Christ at all.”

“

Gediminas retorted that he had never asked to write about his baptism and blamed his Franciscan scribe Berthold. He added, “If I ever had such an idea, may the devil baptize me.”

During the audience at Gediminas’ court, the legates tried to approach the most important topic gently, but Gediminas soon interrupted them and asked if they really knew what was written in his letters. The messengers replied, “The intention to accept the faith of Christ and be baptized.” Gediminas retorted that he had never asked to write about his baptism and blamed his Franciscan scribe Berthold. He added, “If I ever had such an idea, may the devil baptize me.”

The shock therapy was followed by a quieter discussion aimed at digging into what exactly was in the letters.

In trying to vindicate himself, Brother Berthold said that he put down only “what came out of the lips of the king: that he wanted to be the son of obedience and surrender to the patronage of the Church, the Holy Mother, and to accept the faith of Christ.” In response, a man from Gediminas’ camp pressed, “So you admit you weren’t told to write about the baptism?” All the Christians argued that being “the son of obedience” and surrendering to the patronage of the “Holy Mother” means nothing else than baptism, yet the Lithuanians were not impressed by such rationalizations.

Finally, Gediminas did not miss his chance to shine by letting the cultivated men know his take on the pope’s fatherhood to his sonship. Nothing can prevent him from recognizing the pope as his father, for he respects him as a father, “because he is older than me, and I will regard all others older than me as parents; similarly, I consider the archbishop my father because he is older than me; and all who are of similar age to me, I will consider my brothers, while those younger than me will I consider my sons.”

Darius Baronas