Parish schools: priority – religious instruction

In medieval times children must have been happier. Back then, nobody kept telling them about their obligation to go to school.

The so-called bitter roots of education had to be tasted by children. Education was regarded as privilege rather than as obligation. Girls were relieved from the burden of attending school. More attention on daughters’ education was paid only by representatives of the highest society levels, such as rulers and noblemen. Furthermore, not all parents raising sons were concerned with their education. Very few parents could afford to keep a youngster not contributing to the household chores and pay for is tuition. This was a luxury which could only be afforded by boyars, townsfolk and wealthier peasants. Meanwhile, the education of noblemen’s children was entrusted to the care of carefully selected private teachers.

In medieval times, once determined to provide education for their son, the parents were not faced with a dilemma of choosing the most suitable school.

The monopoly of education belonged to the Catholic Church.

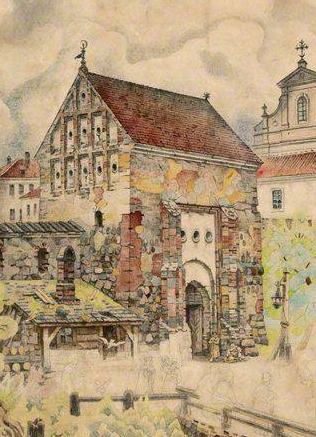

Schools, like churches, were of two types – parish and cathedral-based. Thus, the network of schools was predetermined by the network of churches. In the Great Duchy of Lithuania there were two dioceses – Vilnius and Samogitian, otherwise called as Medininkai diocese. Given these facts, it is easy to draw the conclusion that two cathedral-based schools were operating in the GDL – those of Vilnius and Medininkai. The Vilnius Cathedral school started functioning prior to 1397. It was located on the territory of the present Cathedral square, next to the belfry. The Medininkai Cathedral school was opened in 1469.

Formation of the school network: aspirations and reality

It is not that easy to calculate the number of parish schools, though. During the period in question there was a sharp increase in parish schools. The first seven parishes in Vilnius diocese were established by Władysław II Jagiełło in 1387. In the end of 15th century, 130 parishes were functioning in this diocese. In mid-16th century, Vilnius diocese comprised 259 parishes, whereas the Samogitian diocese had 43 parishes. The goal was set to establish schools in all parishes. This aspiration was also shared by Władysław II Jagiełło, who granted funds to the first churches. The same goal was identified in the resolutions of Vilnius diocesan synod of 1528. In them, church pastors were given explicit instructions to erect a school next to every church and to a boarding house providing accommodation for schoolchildren. Furthermore, funds had to be allocated for teacher’s upkeep allowances. However, these ambitions failed to be realized. The educational programme was developed by the bishop; part of the church foundations granted by rulers and noblemen for church maintenance was dedicated to teacher maintenance allowances (this was not a universal practice). However, the establishment of school itself and recruitment of a teacher fell under the competence of church parsons. There were no control authorities supervising their activities in the sphere of education.

Having perused all relevant sources and counted all references in question, historians presume that about one third of parish schools had schools functioning next to them.

For comparison sake, in Poland, which had been baptised three hundred years before, schools were functioning next to almost every parish church. Due to gaps in school network parents chose to send their children to more remote areas. For example, schools in Kaunas were attended by children from Žiežmariai (40 km distanced from Kaunas) and Vilkija (situated 30 km away from Kaunas).

Religious education in parish schools

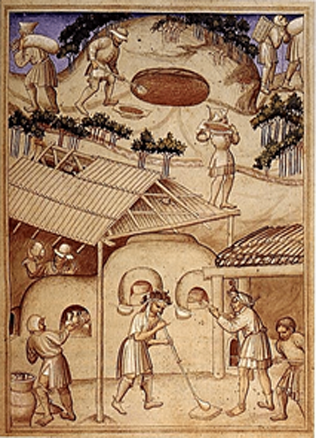

Discussions about the network of schools often remind us of the lines in Martynas Mažvydas’ Cathecism: „Be geresni su šventa burtininke gaidį valgyti,/ Neig bažnyčioj šaukimo žekų klausyti“ (It is better to eat rooster with a sacred conjurer/ rather than listen to the shouting of the pupils). The school children of GDL are referred to as žekai, a non-normative word in the standard Lithuanian of today. The word šaukimas (shouting) means singing hymns at church service. This episode is sufficient proof that in mid-16th century singing performed by school children at church service was a usual tradition observed. It also provides information about the content of school education. School children assisted in holding church service, performed liturgical rite and took part in processions.

Even church founders, upon allocating funds for school maintenance, noted that they did this in pursuit of God’s greater glory of God, not even mentioning the need of educating children.

In medieval times a theoretical educational training programme was developed, which comprised seven liberal arts. The programme was classified into a trivium and quadrium, which means a programme of 3 and 4 subjects respectively. The former contained grammar of Latin language, rhetoric and dialectics, whereas a more advanced quadrium programme consisted of arithmetic, geometry, astronomy and music. These subjects were important for those intending to pursue university studies. This system, however, was ignored in parish schools. The resolutions of Vilnius diocesan synod of 1527–1528 specify that children had to be instructed in writing skills, the established traditions worthy of respect and esteem as well as in the most important truths of the faith. Furthermore, Gospel should be preached, and apostle Paul’s letters analysed both in Lithuanian and Polish.

Using current terms to analyse the curriculum of those days, the conclusion could be drawn that alongside the most significant class in religious instruction, lessons in ecclesiastic chanting and writing were no less important.

The exclusive focus on religious education in school curriculum is also proven by the interest shown by the nuncio Tarquinius Peccolo during his visitation of the Samogitian diocese in 1579. The nuncio was expressly interested whether the church parson showed adequate concern to religious education. The situation related to other school subjects did not seem to bother him to the same extent. Parish members also used to complain about insufficient attention shown to religious education of their children.

Education in accordance with the needs

At that time Lithuanian was not used for writing purposes, therefore lessons in writing usually coincided with foreign language development skills.

Even though Latin was regarded as the most important written language, at least three written languages were used in GDL (Latin, Ruthenian and, from 16th century onwards, Polish), therefore, the choice of the written language was predetermined by local needs and teacher’s knowledge.

In 1579, during the nuncio’s visitation of the Samogitian diocese, a teacher from Ariogala told him that he could not speak Latin, therefore, the school children were instructed in Ruthenian and Polish. A teacher from Krakiai taught school children Latin grammar, virtuous life and the Shorter Catechism, whereas a teacher from Betygala offered instruction in writing skills, grammar and religion. A numerous German community lived at that time in Kaunas, and a German school was established to serve their needs. There is also mention in relevant sources of the Polish school in Kaunas.

In schools set next to cathedrals the level of tuition was more advanced. They could be relatively compared to modern secondary schools or gymnasiums. However, there was little difference in the highlights of the syllabus.

The most advanced school in the Great Duchy of Lithuania until the mid-16th century was Vilnius Cathedral school.

A relevant criterion of today could be used as a quality indicator to prove the point, that is, the number of school leavers enrolled in establishments of higher education. There was a significant prevalence of students from Vilnius among those enrolled in the University of Krakow (101 students from 366, recorded in 1401–1550).

One might get the impression that in medieval times the majority of GDL population was ignorant and uneducated. However, the situation was not dramatic and met the needs of society. A constantly increasing number of Lithuanian students in the University of Krakow from the 15th century is sufficient proof of that. Furthermore, in the mid-16th century Lithuania could boast a number of intellectuals and humanists of Lithuanian origin who were studying in the most famous European universities of that period.

Reda Bružaitė