Residential Castles During Vytautas’ Reign

In the mediaeval Europe, some rulers adhered to the model of travelling kingdom in their countries: they would visit the most important cities and locations together with their courts. This was the way for a ruler to renew and consolidate his personal ties with local aristocracy and officials. On the other hand, regular travel was necessary for a ruler from the economic, administrative and legal point of view, because he would collect scots and taxes, settle disputes and act as a judge during these visits. In addition to that, ruler’s travel served as a symbolic manifestation of his power, a representation and a showcase, especially bearing in mind the contrasts inside the mediaeval society.

Trakai: the key station for the “travelling kingdom”

After becoming the Grand Duke, Vytautas started building a new, in qualitative sense, structure of the state. He strived for that because he had already been acquainted with the structure of the state run by the Teutonic Order. Vytautas shaped the court of the grand duke in accordance to the Western European model. He introduced key official posts that represented and expressed the status of the sovereign ruler. The entire process reflected gradual Europeanisation of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.

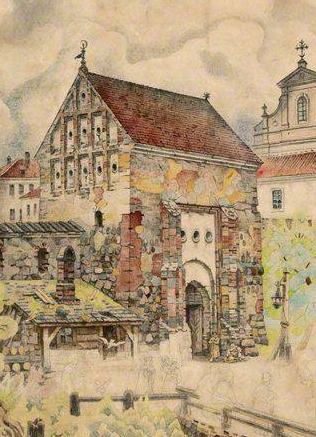

Vytautas built or rebuilt a number of castles at the turn of the 15th century. These were stone residences of a more sophisticated construction. The Island Castle in Trakai, as well as those in Vilnius, Grodno, Navahrudak and Kaunas became main residences during Vytautas’ reign. There were no capital cities in mediaeval Europe in the sense of the modern state. The ruler had several residences within his domain. According to Vytautas’ itineraries, he resided mostly in the Island Castle in Trakai and in castles in Navahrudak, Grodno, Vilnius, Kaunas, and Lithuanian Brest. He usually reduced his activity to the solving the issues of power while visiting other locations of the GDL.

The Island Castle in Trakai was build around 1408 and soon became Vytautas’ main residence.

Apparently, it is possible to assess Vytautas’ subjective motives of choosing that place as the residence he was visiting most often. In this case, there is a parallel between Vytautas and Charlemagne, who had his main imperial residence in Aachen, the city famous for its hot springs. The difference lies in the fact that Aachen was the main sanctuary of the Carolingian Empire, the status later acquired by Reims in France and Cantebury in England. In Lithuania, the main sanctuary was the Cathedral of Vilnius.

Castles grow in line with the ruler’s status: stone replaces wood

Wooden castles, e. g. in Dubičiai, Alytus, Nemunaitis, Punia, Merkinė, Eišiškės and elsewhere, often referred to in the late 14th century, almost never appear in the historical sources of the first half of the 15th century when Vytautas ruled the country. Although we know that Vytautas met Guillebert de Lannoy in Merkinė, the Burgundian knight and diplomat never mentioned any castle in that city in his memoires, but wrote about the Island Castle in Trakai that impressed him and referred to the newly built castle in Braslaw. Ring-fenced castles in Krėva, Lida, and Medininkai faced similar destiny. Vytautas visited the latter three only several times despite the fact that they were within the domain of the Grand Duke.

It seems likely that Vytautas tried to implement the mechanism of power and the structure of its representation while consolidating his authority in Lithuania because he had been acquainted to its forms in the German Order.

Therefore, the old wooden castles did not match either Vytautas’ status or his self-awareness, because he was a sovereign ruler.

Equally, that can be linked to the changes in his title and the formation of his great royal seal and the lesser royal seal. All these processes, that took place simultaneously at the turn of the 15th century, supplement each other by expressing the aspirations of the sovereign ruler.

It is likely that the old castles in the more distant Ruthenian territories (in Polotsk, Vitebsk, Smolensk, Kiev, and Volhynia) were renovated or rebuilt at that time too, but historical sources provide no information on that matter. We can employ certain parallels or analogies in neighbouring countries. For instance, the last ruler of the Piast dynasty, the King of Poland Casimir the Great, not only completed the unification of his country, but also contributed to the spread of residential stone castles. Therefore, any changes inside a country should only be considered in the context of other simultaneous processes.

Ruler’s residence—the secular and spiritual centre

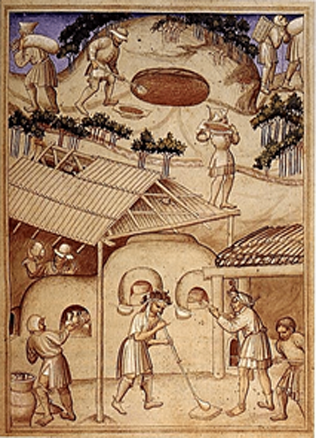

The residence and its concept cannot be reduced to a castle, as a separate object. The residence is multifunctional and serves for representation. Hence, residences were the places where secular and religious functions interwove. To express it secular power, it used local and central officials, such as elders, vicegerents, castellans, voivodes, and marshals of the court. A chapel or a church represented the religious function of the residence, together with a one more important building of worship outside the castle. The castles in Kaunas and Trakai are the characteristic examples of that model. Vytautas founded churches there in about 1408, the time when the two cities were granted the Magdeburg Rights.

A number of other churches were founded and new parishes were established during the years of Vytautas’ reign, from the late 14th century to 1430. Some of them emerged in towns and cities which earlier had castles, including Maišiagala, Medininkai, Krėva, Braslaw, Dubingiai, Grodno, Kernavė, Lida, Merkinė, and Navahrudak. The 1421 founding of the new castle in Veliuona, where a wooden castle was still standing at that time, stands out as an exclusive episode, because it reveals the importance of that area and Vytautas’ aspirations regarding the representation of his authority. Of all the aforementioned towns and settlements, only several later became residences for Vytautas. On the other hand, erecting a church or establishing a parish both were important conditions for any settlement to become the ruler’s residence.

The residence is a complex structure. A castle or a ducal estate was not enough, although the first parishes were established in Daugai and Nemenčinė, the settlements with ducal estates. To become a residence, the place must bring in various functions and guarantee they are properly performed, because the residence represented the Grand Duke as a sovereign ruler. Therefore, the residence was required to amass both local and central officials that Vytautas had begun putting in place. At the same time, the residence was expected to shape the religious life of the area. Residences had to bring together the then barely visible social group of city dwellers, an important piece in filling up the mosaic of the mediaeval society.

Vytautas Volungevičius