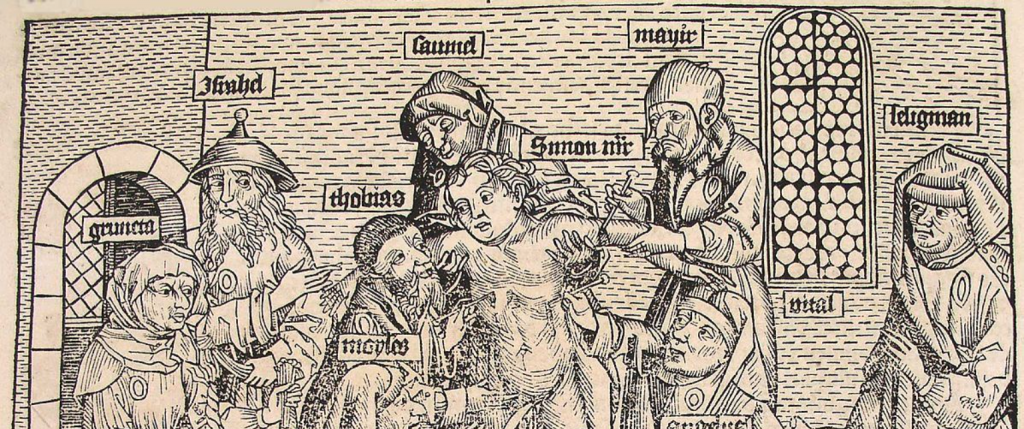

Simonas Kerelis, the Victim of a Rumoured Ritual Murder

In Medieval Europe, England and France in particular, many Christians believed that during Pesach, the holiday commemorating the Jewish Exodus from Egypt, Jews re-enact the crucifixion of Christ and use the Christian children’s blood during the ritual.

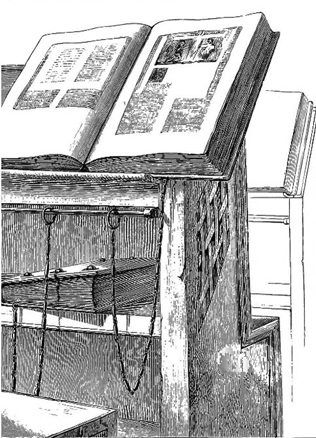

Jesuit theologian and the first rector of Vilnius University Piotr Skarga introduced the narrative to a broader audience of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. In his book “The Lives of Saints” (1577) he wrote that the Jews tortured Simonas Kerelis, a seven-year-old boy from Vilnius, to death. This was supposedly carried out in Skarga’s lifetime, while his book enjoyed more than 20 editions by the end of the 18th century.

Narrative turns historical

“

By 1623 the boy was regarded beatified, his reverence cult spreading throughout the city. The residents of Vilnius cared for his relics, prayed at his grave, and brought votives. Simonas Kerelis, however, never made it to the official list of the beatified Christians recognized by the Catholic Church, let alone that of the saints.

Historian Albert Wijuk Kojałowicz also wrote about a boy killed by the Jews in his “Historical Miscelania on the State of the Church in Lithuania” (1650): “Seven-year-old boy of Lithuanian descent, born in Vilnius, was killed in 1592 by the Vilnius Jews, who stabbed him to death with knives and scissors with utmost cruelty. He suffered 170 wounds, moreover, he was tortured by shoving splinters under his fingernails. He was buried in the church of Bernardine fathers in Vilnius. Later on, in 1623, his body was moved to a marble grave outside the church.”

By 1623 the boy was regarded beatified, his reverence cult spreading throughout the city. The residents of Vilnius cared for his relics, prayed at his grave, and brought votives. Simonas Kerelis, however, never made it to the official list of the beatified Christians recognized by the Catholic Church, let alone that of the saints.

The two Simons

“

According to unverified sources, in the early 18th century the boy’s relics were installed in the church altar dedicated to the Magi. Later his tiny marble coffin was at least twice reburied in other locations. Today all that reminds visitors of Simonas Kerelis is a memorial plaque on the wall of the Bernardine Church.

We know little of Simonas from Vilnius. In many details his story is similar to that of his namesake, an Italian boy from Trent. As legends would have it, both boys suffered the same number of stabbing wounds, 170. But Simon the Italian died more than a hundred years earlier, in 1475. His relics were displayed before the participants of the Council of Trent (1545–1563). Pope Sixtus V officially introduced Simon of Trent’s cult in 1588. Curiously enough, only four years separate his beatification and Simonas Kerelis’ death in the year 1592.

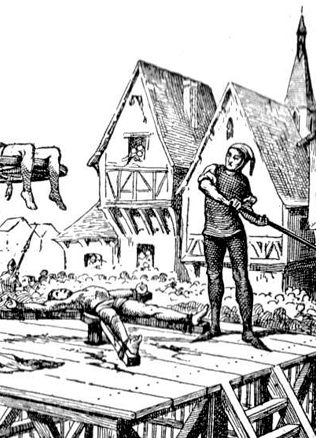

The Bernadine monks in Vilnius had a good reason to promote “their Simon’s” cult, because arriving pilgrims donated considerable sums of money. It subsided during the years of the so-called Deluge (1655–1661), when Vilnius was occupied by the Muscovites. They devastated the city and the Bernadine Church where Simonas’ marble sarcophagus was destroyed.

According to unverified sources, in the early 18th century the boy’s relics were installed in the church altar dedicated to the Magi. Later his tiny marble coffin was at least twice reburied in other locations. Today all that reminds visitors of Simonas Kerelis is a memorial plaque on the wall of the Bernardine Church.

Christians and myths about the Jews

Skarga, a respected Jesuit author, deviated from tradition. The Catholic Church has long dismissed the allegations that Jews used the blood of Christian children in their religious ceremonies. Such suspicions were deemed baseless, therefore the Church spoke against associating the Jews with ritual killings of the Christians. This was set in the 1388 privilege to the Jews, issued by Grand Duke of Lithuania Vytautas the Great. Despite that, myths kept spreading. They grew more elaborate and eventually replaced Christian children with murdered adults.

The stories popular in the GDL featured a multitude of harrowing details about the wounds inflicted to the alleged victims. By the late 18th century, much later than in Western Europe, the narrative expanded to include unleavened bread, matzos, that the Jews bake for Pesach – using Christian blood, of course. Later on, even more elaborate versions of the faux story emerged.

Do You Know?

Indeed, some medieval medics and magicians insisted that the blood of innocent children had miraculous powers. Stories of the Jews murdering gentiles date back to Democritus, a 5th century BC Greek philosopher, who wrote about a ritual sacrifice of a Greek man kept in a synagogue and well fed prior to the killing.

Jan Serafinowicz, an 18th century Jew turned Christian, calculated how much blood the Jews of the GDL required to perform their religious rituals. Some modern historians suggest that Serafinowicz suffered a mental disorder, but his contemporaries must have readily believed the formed rabbi who, in their view, had access to the innermost Jewish secrets and perhaps even carried out ritual murders himself.

By Jurgita Verbickienė