Of Death Penalty and Christian Clemency in Vilnius

Historical sources describing public executions in medieval Lithuania are very scarce, making even the smallest pieces of information highly important.

Do You Know?

In pagan Lithuania, the death penalty roughly corresponded the custom of blood revenge and rites of prisoner sacrifice, but these practices did not require the approval of the supreme authority. In the late Middle Ages, as the power of the Grand Duke of Lithuania strengthened, public executions became part of his monopoly of power. Only his court could sentence a noble offender to capital punishment.

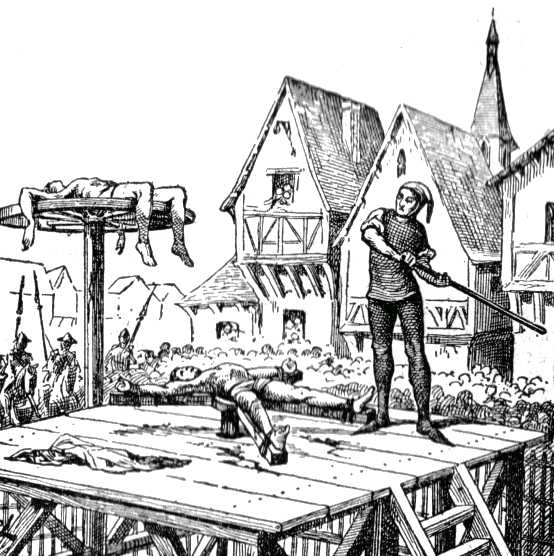

Stanislovas, the fratricide, steps on the scaffold

The story we shall relate here is one of very few source-based cases concerning capital punishment in 16-century Vilnius. The story is unique in its detailed description of the path from trial to execution.

In his royal residence in Vilnius Alexander Jagiellon (1492–1506) convicted a nobleman Stanislovas Butkaitis for fratricide and sentenced him to death. Kasparas and Venclovas, his surviving brothers, acted as plaintiffs in this case and provided the court with conclusive evidence, hence the trial was short.

“

Curiously enough, the men and women gathered in the square were supposed to become, in a sense, participants of Stanislovas’s death, rather than just witnesses of the execution which, presumably, could not go on without the audience. It is worth reminding that Stanislovas was a nobleman. Other nobles watching his execution were meant to ensure that the capital punishment was rightful.

More than ten year later Kasparas had this to say about the case. “His Grace the Grand Duke Alexander heard the case alongside the Council of Lordsand as my brother had been found guilty, the ruler ordered that for committing such violence he be given to the Town Hall and executed.”

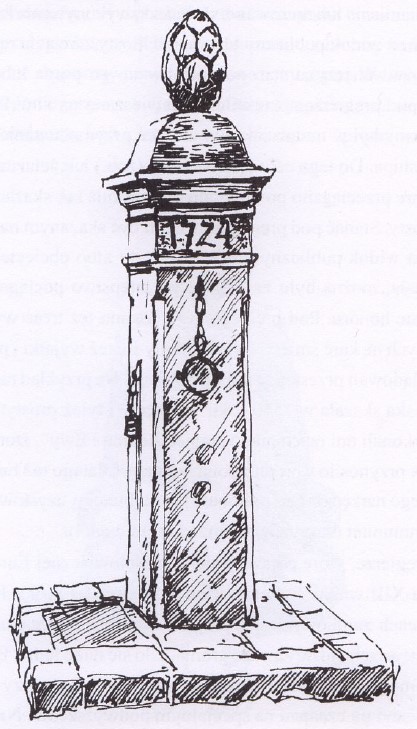

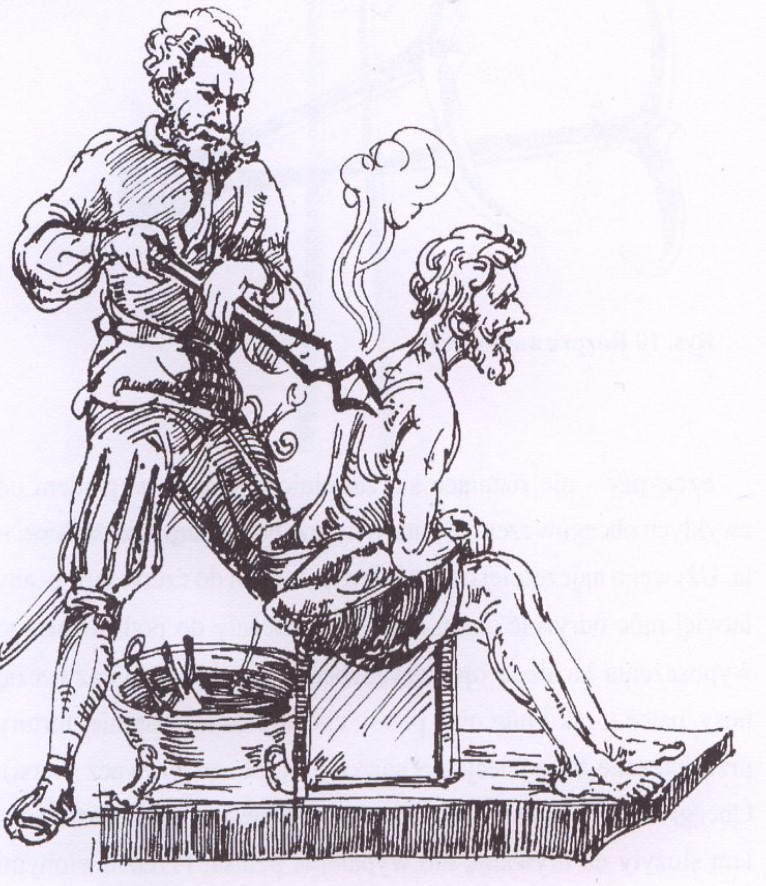

After the court announced its verdict, Stanislovas was immediately taken to the square next to the Town Hall, the usual place for public executions. Beheading was the most common form of capital punishment, yet some criminals were sentenced to be burned alive. The latter method was adjudged for forging royal documents, since counterfeiters were classified as traitors.

Shortly after Stanislovas entered the square, spectators began to gather. According to Kasparas, „We were taking him to the Town Hall escorted by a court official appointed by the duke; we were accompanied by an adequate number of other good people, ruler’s nobles.”

Curiously enough, the men and women gathered in the square were supposed to become, in a sense, participants of Stanislovas’s death, rather than just witnesses of the execution which, presumably, could not go on without the audience. It is worth reminding that Stanislovas was a nobleman. Other nobles watching his execution were meant to ensure that the capital punishment was rightful.

The executioner takes the victim’s clothing

“

His personal belongings were meant to become the executioner’s property, in line with the tradition of the day. Paid from the municipal treasury, sometimes executioners were extremely lucky. One of them found 18 Polish zlotys inside a shoe, the money that could buy four cows or two oxen.

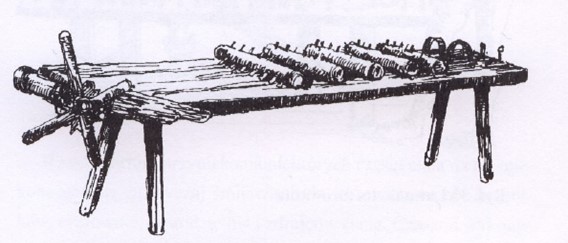

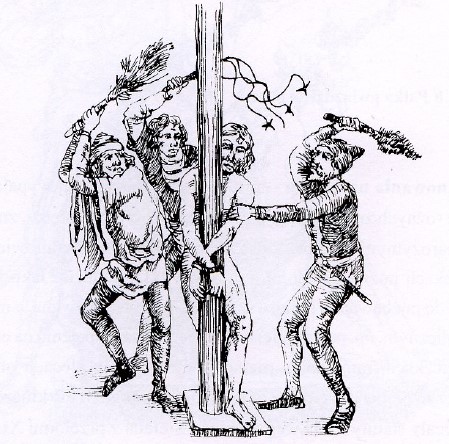

The court officer was responsible for overseeing the administration of justice. It seems that it was him who took the sword from Stanislovas, tore off his hat, pulled off his outerwear, and removed his shoes once they reached the Town Hall. Standing almost naked, covered only by a linen shirt, Stanislovas apparently felt profoundly humiliated as he was deprived of his hat and sword, the key symbols of his descent and social status.

His personal belongings were meant to become the executioner’s property, in line with the tradition of the day. Paid from the municipal treasury, sometimes executioners were extremely lucky. One of them found 18 Polish zlotys inside a shoe, the money that could buy four cows or two oxen.

Confession preceded the execution

But let’s allow Kasparas to continue his story. “Once we brought Stanislovas to the Town Hall, he started asking for a confession, and we granted his request.” In a Christian society, the Sacrament of Confession and the Eucharist were the two most important steps in preparing for death. No wonder Stanislovas’s plea was granted. Followed by a crowd, the convict was taken to the Bernardine Monastery to confess.

“

In a Christian society, the Sacrament of Confession and the Eucharist were the two most important steps in preparing for death.

Shortly after Stanislovas had confessed his sins and accepted the Holy Communion, according to Kasparas, he “sent Bernardine fathers and other clergymen to plead for our mercy.”

Such a request should not seem unusual, even from the perspective of our time. In some places nowadays, for instance the United States, death row inmates are sometimes commuted to life imprisonment.

The law in medieval Lithuania was similar, stating that even after the court had announced its verdict, the plaintiffs could reconcile with the defendants or acquit them. And that’s what happened with the poor Stanislovas.

“

No special court order was required to revise the sentence issued by the Grand Duke’s Court. The plaintiffs held the power to grant mercy to a person sentenced to die.

Kasparas described the denouement in the following words: “After consulting with our brother Venclovas, we did not send Stanislovas to death, we released him instead to repent his sins.“

No special court order was required to revise the sentence issued by the Grand Duke’s Court. The plaintiffs held the power to grant mercy to a person sentenced to die.

Stanislovas, a lucky man

Little is known about Stanislovas’s later life. Historical sources suggest that his brothers sent him to repent his sins in exile, living on a small estate near Orsha, in present-day Belarus. There he married and fathered two sons but was soon murdered at the hands of Muscovites raiding the area.

Had not his brothers shown mercy on him, Stanislovas’s fate would have been very different. After confessing his sins and taking the Holy Communion, he would have been led back to the Town Hall Square where he would be met by the executioner, wielding a double-edged sword. Stanislovas would be bent down on his knees, blindfolded, and utter his last words. Those would have been cut short by the edge of the sword.

It is unclear if the bodies of the executed were buried in accordance with Christian customs. Archaeological excavations in Vilnius have revealed that the remains were buried in a secluded ditch outside the city walls and, often, in secret.