Old Vilnius after Nightfall

History of night differs from that of day. Many societies regarded darkness with fear and the night as the time of evil forces and the devil. The night makes some people feel uneasy, others suffer from nyctophobia, an extreme fear of night or darkness. On the other hand, it serves as a symbol of divine mystery and a source of inspiration for poetic souls.

Weddings at night were prohibited since times immemorial, but watchmen, street sweepers, cooks and bakers, prostitutes, monks, executioners, and burglars always laboured all night through. And just as today, the young would spend it having fun and forging new friendships.

Paris, Berlin, Vilnius

History reminds of many horrible atrocities committed under the cover of darkness. Parisian Catholics killed several thousand Protestants during the St Bartholomew’s Night Massacre (1572); Nazis killed the potential rivals of Adolf Hitler during the Night of the Long Knives (1934), while the Crystal Night (1938) preceded the systemic mass extermination of Jews.

Lithuania also had its share of violent nights. 16th century historian Maciej Stryjkowski wrote that Grand Duke of Lithuania Jagiełło took two Vilnius castles in 1382 “when people were resting after their daily chores, having given themselves to sweet dreams in the darkness of night; Hanul, the castellan, opened up the gates and left a lantern hanging outside as a sign of treachery. Jagiełło and the Germans attacked the castles immediately, killing many of their defenders still asleep and capturing others.”

Nocturnal life

Since the early 16th century, Western societies have developed ways of “colonizing the night”. Artificial lighting enabled to prolong all kinds of activities after the daylight hours. Light itself became the symbol of progress and rationality. The Age of Enlightenment, as a term denoting the era marked by elevation of the sciences and the arts, also bears interesting connotations.

“

The Vespers marked the threshold into the night that lasted until sunrise. Personal timepieces were extremely rare and forbiddingly expensive, but the urban population tracked time according to the clocks in the churches and the tower of the Town Hall.

Did all residents of old Vilnius sleep at night? You would be wrong to think so. Several centuries ago night life was quite dynamic.

The Vespers marked the threshold into the night that lasted until sunrise. Personal timepieces were extremely rare and forbiddingly expensive, but the urban population tracked time according to the clocks in the churches and the tower of the Town Hall.

In the 16th century, when a defensive wall was built around Vilnius, closing of all city gates at sunset became another ritual marking the beginning of the night. This was a precaution taken to secure the city, while the citizens had to guard their persons and possessions themselves.

Ordinary people had to have a very good reason to walk the streets at night and could only do so bearing a lantern, otherwise they could spend the night in prison.

Private houses were guarded by gates

“

Such gates were locked upon nightfall and house owners were in their full right to ignore the knocking tenants. On the other hand, at night many drunkards and brawlers stood around at the gates. Were we to believe the archival sources of the 16th century, alcohol has flown freely in the houses of Vilnans and pleasant evenings often ended in altercation.

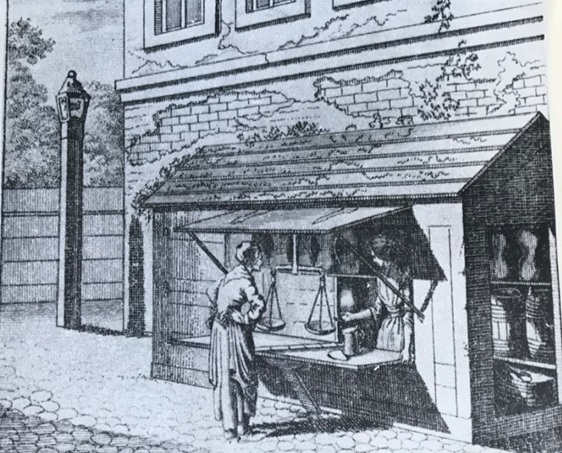

Just as in other European cities, private houses were guarded by strong gates. The living quarters were reachable through a courtyard, while the stores and taverns located on the ground floor were readily accessible from the street. as a precaution against burglars, citizens shuttered their windows.

Such gates were locked upon nightfall and house owners were in their full right to ignore the knocking tenants. On the other hand, at night many drunkards and brawlers stood around at the gates. Were we to believe the archival sources of the 16th century, alcohol has flown freely in the houses of Vilnans and pleasant evenings often ended in altercation.

Hired watchmen guarded the peace at night. They were joined by merchants and artisans, who were obliged to patrol at night. The job was very dangerous, because dozens of criminals and drunkards roamed the streets. Inebriated gun or sword-bearing nobles often caused a ruckus. Many a night guard suffered injuries and even was deprived of his life at their hands. The areas outside the city proper were very dangerous, even the most courageous rarely ventured beyond the gates.

Only natural light

After the sunset, darkness enveloped the streets of old Vilnius, unless the skies were clear at a night of full moon. The royal residence in the Lower Castle was the only exception. The first street lamps were installed beside the palace back in the second half of the 16th century. Later on, in the early 1700s, more lamps were set by Vilnelė. Lamplighters employed by the court took care of them.

Across the rest of the city, most windows were pitch dark. Only rich people could afford candles, let alone fireplaces.

“

The city would burst into light during religious and secular holidays, because the Town Hall, main churches, and magnate palaces were illuminated. Gas lighting was first introduced in Vilnius in 1824, just about in time with other cities across Europe and North America.

The city would burst into light during religious and secular holidays, because the Town Hall, main churches, and magnate palaces were illuminated. Gas lighting was first introduced in Vilnius in 1824, just about in time with other cities across Europe and North America.

Many pious residents of Vilnius spoke against the street lights, they insisted that those distort the order set by God according to which nights must be dark. Light, they maintained, encouraged people to drink, sin, commit crimes, and spread diseases.

Nocturnal activities

Most people spent the night sleeping, yet only the well-to-do could afford beds and bedding. Majority of Vilnans slept on benches, coffers, or an armful of hay strewn on the floor. Only rich merchants and artisans had nightwear, chamber pots, pillows, and rocking beds for children. Servants often spent nights in unheated rooms and barns.

Do You Know?

Some two hundred years ago, most people were still used to the so-called “sleep break”. Usually people went to bed at around nine in the evening and slept for the next three hours. They would then wake up and get to anything, some prayed and read, others were smoking or making love. It was during the “sleep breaks” that many children in old Vilnius were conceived.

Sleeping the whole night without a major interruption is a relatively recent phenomenon. In Lithuania the new “tradition” began spreading in the 19th century, in line with street lighting and increased security which, in turn, prompted the rise of what we now call nightlife. Only the wealthy slept without breaks, because their day would often end after midnight.

Taverns, brothels and all that

“

Many aspects of nightlife bore similarity to what we are used to nowadays. After the nightfall, thieves would pour into the streets eyeing the drunken or careless passers-by and their cash, clothing or guns. Outside the city centre, a number of illegal brothels operated. On the other hand, many ordinary people tried to have fun at home with their friends, next of kin, and neighbours.

Centuries ago, just like now, dozens of taverns worked throughout the night. Many of them were notorious for excessive consumption of beer, mead, and vodka. Some visitors apparently resorted to violence only to flee the place without paying for food and drinks.

Many aspects of nightlife bore similarity to what we are used to nowadays. After the nightfall, thieves would pour into the streets eyeing the drunken or careless passers-by and their cash, clothing or guns. Outside the city centre, a number of illegal brothels operated. On the other hand, many ordinary people tried to have fun at home with their friends, next of kin, and neighbours.

Archival documents from a municipal court of law tell real-life stories from the 1560s.

Of Eska, a Jew, who tried to rape Anna the inn-keeper, and since she fought back, he rewarded her with a bad cut on her hand and forehead. Of Stanisław Leśniewski, who was beaten in his bed and lost a sword and some of his clothing. Of a trumpeter Gregory, who, woken up by his candlebearing friend organist Jan Palecki, was so frightened that he killed the organist. Of two smiths, Piotr and Grigory, whose conflict turned murderous.

And of the lucky man Grisha, who, albeit bound in chains, escaped from the castle prison nonetheless.

When night becomes day

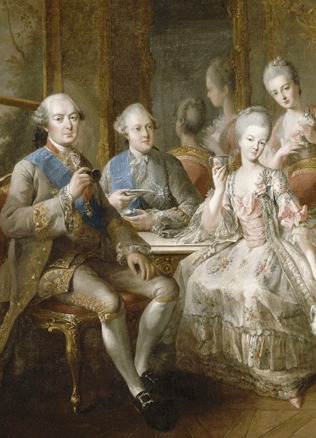

The rich and the mighty also spent many nights awake, mostly at grand parties that included splendid fireworks rising high above the city. Long dancing sessions and copious dinners usually lasted until three or four o’clock in the morning.

“

To celebrate birthdays and name days of the influential officials and the ruler, artillery was employed. The birthday of an influential magnate was commemorated by a hundred cannon blasts, shot one by one. In 1754, sixteen cannons thundered simultaneously to mark the birthday of King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania Augustus III.

To celebrate birthdays and name days of the influential officials and the ruler, artillery was employed. The birthday of an influential magnate was commemorated by a hundred cannon blasts, shot one by one. In 1754, sixteen cannons thundered simultaneously to mark the birthday of King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania Augustus III.

In addition, impressive firework displays were organized to honour the ruler, oil lamps and candles lit the main city streets, the Town Hall and its tower, impressive illuminations rose above Neris, featuring the triumphal arch, the sigil of Poland-Lithuania and Saxon dynasty, crowned royal portraits, etc.

Pious people often gathered in nocturnal vigils. In June 1716, celebrating the arrival of the statue of Jesus in the garden of the Sapieha Palace, many men and women sang throughout the night.

By Aivas Ragauskas