The Miracle of Ash and Sand: The First Glasshouse in Vilnius

The decisions Lithuanian rulers made several centuries ago would raise a few eyebrows today. One of such decisions was handing over the right to practice a trade to a single artisan, effectively making him a monopolist. This is exactly what happened in the 16th century Vilnius when the right to manufacture glass was limited to one person.

The lucky man’s name was Marcin Palecki. In 1547 King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania Sigismund Augustus granted the privilege making him the only legal producer, importer, and trader of glass in Vilnius.

The promising craft of glass making

In working with glass, Marcin was following in the footsteps of his father Jan, who took over the glass trade from his namesake bishop of Vilnius in 1525. New discoveries show that Bishop Jan was a businessman in a cassock and established the glasshouse in 1519, dating the start of glass making in Vilnius no less than three decades earlier than previously believed.

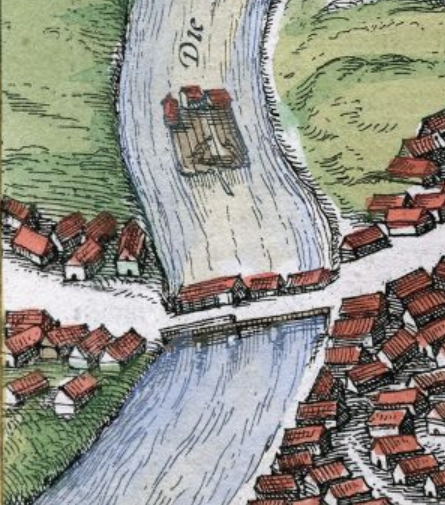

The glasshouse stood on the bishop’s private land outside the city walls, near the present-day Green Bridge, then known as the Grand Bridge. Six years later, on 4 November 1525, the bishop sold it to “the Polish glass maker” Jan Palecki.

Do You Know?

Vilnius was the first city in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania to launch a glass workshop to meet the ever-growing demand spurred by wealthy local residents, foreign visitors, the residing rulers of Poland and Lithuania as well as the most prominent dignitaries of the state.

“

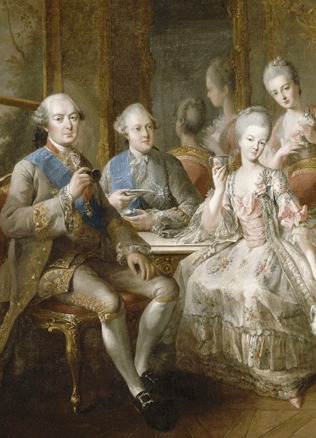

By 1544, when King Sigismund Augustus arrived in Vilnius and settled here with his royal court, Jan Palecki’s glass works had ceased operation, however the exact reason and time of it shutting down remains unknown. For a few years the king and his courtiers bought glassware imported from Venice, France, and Belgium. Window glazing materials, such as iron, lead, and tin, came from Austria.

The Vilnan glasshouse was one of the first of its kind in Eastern Europe. Although the territory of today’s Latvia is full of quartz sand, the first glass workshops opened there only in the 1560’s.

It is hard to evaluate the technical skill of the Vilnan glasshouse. Most likely, it could not supply top quality seamless glass, but rather products of green or yellow tint, almost opaque and showing impurities, such as residual ash. In this respect, Vilnius glasshouse was no different from many other mediocre workshops across Europe.

By 1544, when King Sigismund Augustus arrived in Vilnius and settled here with his royal court, Jan Palecki’s glass works had ceased operation, however the exact reason and time of it shutting down remains unknown. For a few years the king and his courtiers bought glassware imported from Venice, France, and Belgium. Window glazing materials, such as iron, lead, and tin, came from Austria.

The millionaire artisan

Jan Palecki’s son Marcin (d. 1588) revived the interrupted tradition of glass making. As a royal courtier, he lived under the patronage of one of the most influential magnates of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, Mikołaj Radziwiłł the Black.

“

His wealth grew too. He owned a plot of land in Vilnius where he established a glass workshop and a built house. Moreover, he owned a brick house beside the Town Hall and several country estates with more than 4,500 hectares of land.

Having secured monopoly rights in the glass market, Palecki became a Reformed Evangelical and soon achieved success. His wealth grew too. He owned a plot of land in Vilnius where he established a glass workshop and a built house. Moreover, he owned a brick house beside the Town Hall and several country estates with more than 4,500 hectares of land.

His glass shop, where locally made and imported products were on offer, apparently was on Stiklių [Glassmakers’] Street no. 5 at the heart of the old city. Today the house bears a plaque to honour Marcin Palecki.

He grew so rich that he eventually lent money to the royal court. King Stephen Báthory himself borrowed a huge sum of 6,000 zlotys from Palecki giving him the town of Eišiškės as a collateral.

Vilnius residents oppose the monopoly

“

The royal privilege granted to Palecki in 1547 exempted him from all taxes. In exchange he assumed an obligation to supply the royal court with “200 large blown glasses and 200 smaller glasses each year” and was expected to set “fair and decent” prices for glass products sold in Vilnius.

The royal privilege granted to Palecki in 1547 exempted him from all taxes. In exchange he assumed an obligation to supply the royal court with “200 large blown glasses and 200 smaller glasses each year” and was expected to set “fair and decent” prices for glass products sold in Vilnius.

Other glass merchants were furious. Forced out of the legal trade, they attempted to liberalise the market in 1551 by addressing the king directly, but to no avail. Things turned worse, as Sigismund Augustus soon confirmed his privilege and added that “no other will have a glass workshop in the city of Vilnius”. In all likelihood, the all-powerful Radziwiłł used his influence to ensure Palecki would not lose his exceptional position.

Having lost the case, his potential rivals did not try to challenge Palecki’s monopoly until the death of Sigismund Augustus in 1572. During the reign of Stephen Báthory (1576–1586) several glass artisans and traders went to Warsaw and lodged a complaint in the Sejm of 1582. They argued that the monopoly was contrary to the city’s rights and freedoms.

Network of illegal trade

Monopolies often encourage unauthorised trade and other illicit activity. This is exactly what happened in Vilnius. In a complaint Palecki wrote in 1584, he claims that “Germans, Scots, and other immigrants” as well as local people constantly violate the privilege by “buying and selling window panes and other glassware from Prussia and Poland”. The damage, clearly overstated, was set at an astronomical 40,000 groschen.

Shortly afterwards, in 1585, parliament in Warsaw endorsed Palecki’s monopoly, but said it would lapse after his and his wife’s death. Palecki reportedly agreed with the decision and claimed his main concern was “leaving good memories of himself”.

Do You Know?

However, Vilnans continued to violate the agreement and dealt in smuggled glassware. Interestingly, the courts often ruled in favour of the lawbreaking Vilnans. One Rudys and his wife were acquitted just because the husband said, under oath, he was unaware of his wife’s illegal dealings, while she argued she had had no idea this was against the law.

Born of sand, ash and fire

For many years, and not only in Lithuania, glass products were almost non-existent in the lives of ordinary people. By the 16th century only the richest Vilnans could afford glass windows or Venetian glass goblets on their tables.

Quartz sand and plenty of firewood were the two vital materials for glass production. There was no shortage of forests or sand in Lithuania, but glassmaking was hampered by purely economic factors: local glassware was considerably less profitable at that time than trade in tar and potash, let alone the export of timber.

“

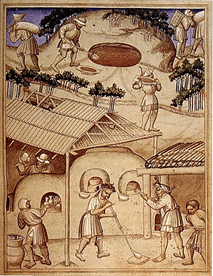

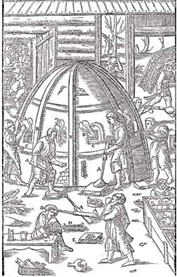

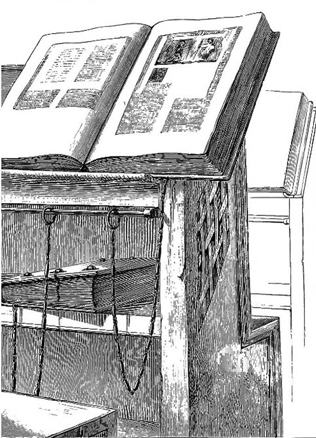

To make simple glass, a master mixed one part of quartz sand with two or three parts of ash. Higher quality glass was produced by mixing sand, lime, potash, and various additives.

To make simple glass, a master mixed one part of quartz sand with two or three parts of ash. Higher quality glass was produced by mixing sand, lime, potash, and various additives.

Ash was produced by burning firewood in pits deep in forests. Glass-melting furnaces were built of refractory clay to withstand temperatures of up to 1250°C. The entire process, dangerous and harmful to health, usually took at least 36 hours and could last up to three days.

By Raimonda Ragauskienė