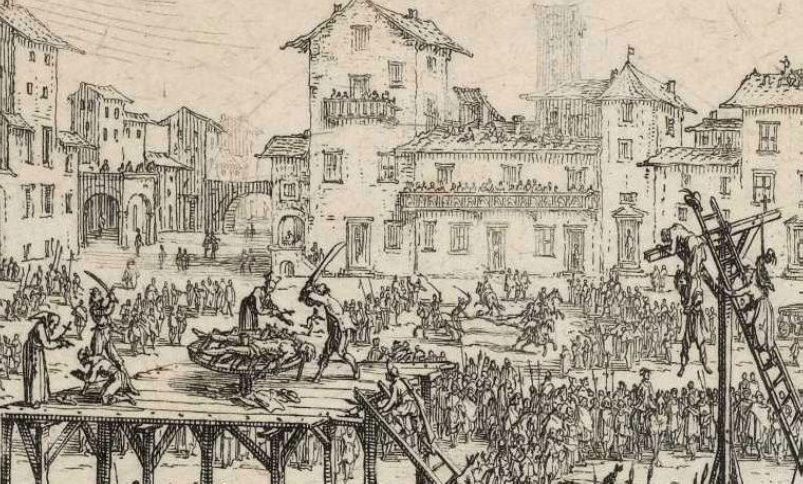

The Theatre of Punishment in the Town Hall Square

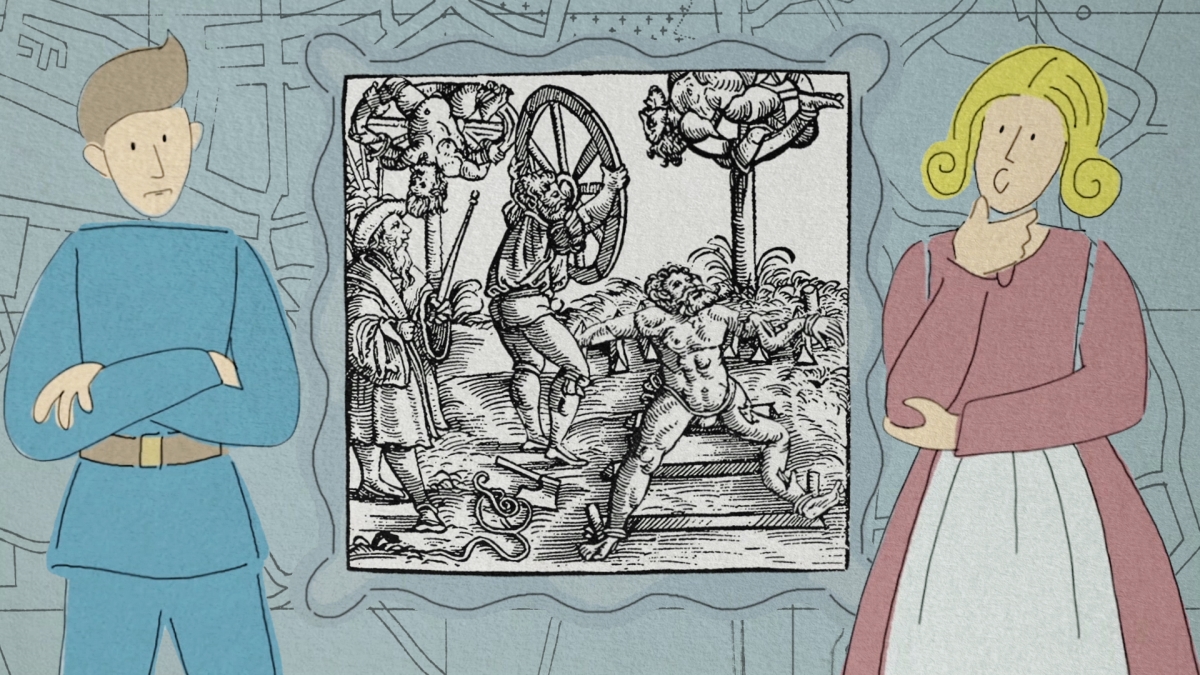

Whenever justice was to be served in the form of public execution, a wooden platform rose in the Town Hall Square, it was called the theatre. Magicians, murderers, thieves, counterfeiters, and all sorts of criminals ascended it to meet their death.

The executions were made public to deter people from criminal behaviour. The practice of public punishment was well alive until the late 18th century, when the punishments and the details of their enactment were announced in the local newspapers.

From whipping post to an executioner’s sword

The mildest punishments were usually carried out at the whipping post, also known as the ‘pilot’. Made of wood and fitted with iron hooks, it also stood in the Town Hall Square of Vilnius. It was primarily used for whipping, but sometimes the chained offender would lose his or her ear for committing petty crimes, such as minor theft or brawl. Sometimes the punishment was limited to chaining a person to the whipping post for an hour or two. On other occasions the court would adjudge five hundred or even a thousand lashes. Not even the strongest men could survive such beating.

“

In 1752, an apprentice received thirty-five lashes and spent three weeks in prison for beating his master. A thief who stole several candles from the Church of All Saints was punished with thirty lashes and three hours of “sitting in the block.” Several shoplifters lost one ear each in 1672 after the encounter with the executioner at the “pillar of shame.”

In 1752, an apprentice received thirty-five lashes and spent three weeks in prison for beating his master. A thief who stole several candles from the Church of All Saints was punished with thirty lashes and three hours of “sitting in the block.” Several shoplifters lost one ear each in 1672 after the encounter with the executioner at the “pillar of shame.”

Grave offenders climbed the ladder to the stage of the punishment theatre, where they would be quartered or beheaded. The assistants of the executioner took the dead bodies outside the city walls where poor local peasants buried their remains. Their services were paid for by the city. Sometimes the quartered body parts were displayed on stakes beside major roads or in the fields.

Archaeologists have found the remains of the executed men and women in several locations next to the wall of Vilnius, in the vicinity of the former gates of Trakai and Subačius, and the surviving Gates of Dawn.

No city of saints

Just like other larger cities, Vilnius was a place where all kinds of criminal activity occurred. Individual lawbreakers, local criminal gangs and, occasionally, travelling thieves, burglars, crooks and other felons paved its streets.

“

Just like other larger cities, Vilnius was a place where all kinds of criminal activity occurred. Individual lawbreakers, local criminal gangs and, occasionally, travelling thieves, burglars, crooks and other felons paved its streets.

On 4 February 1787 Gazeta Wileńska wrote: “It has been a while since villains began inflicting considerable damage on the locals. The attempts to mare at least one arrest proved unsuccessful. On the contrary, the robbers have grown so self-assured that they nailed sheets of paper on the city gates reading that no one will capture them whatever the effort.”

But not everyone evaded justice. On 10 June 1787, the paper wrote about two thieves who had robbed a shop. One of them was adjudged the capital punishment, while the other faced two hundred lashed at the whipping post. On 8 July 1787 the same publication reported that “municipal officials pursue criminals every day and the numbers have increased significantly. Seven of them have been detained recently; they confessed to belonging to a gang of about sixty thieves who planned to rob rich homes and estates.” On 21 December of the same year the paper wrote that “the number of lawbreakers has gone up to the extent that local prisons can no longer accommodate them, two or three being brought in daily.”

The epicentre of punishment at the heart of the city

It was in the Town Hall Square that all the criminals sentenced by the Supreme Tribunal of Lithuania and other courts of law faced punishment. In the summer of 1732, a youngster who had murdered his mother was executed there. “At first, the executioner tore his flesh with pincers; then his right hand was chopped off before quartering him alive. His servant Mikłosz was quartered alive too. A peasant who has taken part in the murder is to be whipped by the executioner for three days, suffering 50 lashes daily, and then expelled from the city”.

The Town Hall was the place where the criminal cases were heard. The suspects were held in its cellars serving as a municipal prison. No doubt, every night and day they heard harrowing screams of men and women under torture, an indispensable tool of any criminal investigation at the time.

Three stages of torment

Do You Know?

Anyone suspected of committing a serious crime, such as theft, burglary, blasphemy, homicide, witchcraft, sodomy, money counterfeiting, rape etc., faced torture, a universally accepted phase of criminal prosecution leading to capital punishment. The laws, however, spared several categories of men and women from torture, including the nobility, those with doctor’s degree, girls and boys under fourteen, pregnant women, and elderly people suffering of dementia.

Torture was merciless, yet it rarely fatal, because the executioner wished to extract the truth and prepare a suspect for the trial rather than kill him.

After the torture, a defendant was expected to repeat the confession during a court hearing “of his own free will” in preparation for the “God’s trial.”

Usually just one session of torture was enough, although the executioner had a right to repeat it two more times, according to the law. Second and third round was required only if the defendant did not want to confess his wrongdoings or new evidence surfaced.

Rope-stretching and candle-burning were the two most popular methods of torture in Vilnius.

From quartering to burning alive

“

Beheading was a traditional method of execution for homicides and other serious crime, including, curiously enough, theft of liturgical items from churches. Most witches, sorcerers and those rejecting Catholicism could expect nothing less than being burned alive at a stake. Often the judges would send them to undergo an additional spell of torture.

For grave offenses, the courts of law usually administered capital punishment by beheading, quartering, hanging, burning alive, or drowning. Beheading was a traditional method of execution for homicides and other serious crime, including, curiously enough, theft of liturgical items from churches. Most witches, sorcerers and those rejecting Catholicism could expect nothing less than being burned alive at a stake. Often the judges would send them to undergo an additional spell of torture.

For murderers and burglars, quartering was the usual sentence. The executioner would then hang parts of their bodies on hooks for the entire city to see. On the stage of the theatre of punishment, the executioner performed with his double-edged sword. One such tool, known as “the sword of justice”, disappeared in the early 20th century.

Just like in many other European cities, the gallows stood beyond the city wall. The area next to the Gate of Dawn, known as the gallows or the Franciscan hill, was owned by the Franciscan monks who collected annual fees from the city for the use of their land.

The most famous executions held in the Town Hall Square

The first high ranking official to be put to death in the Town Hall Square was Jan Wiktorin Giedroyc, when he was quartered and his servant beheaded for high treason in 1563.

“

Perhaps the most famous execution to take place in the 17th century Vilnius was the one of Russian duke Danilo Myszecki. During the first occupation of Vilnius (1655-1661) he served as the voivode of the city and earned the fame of being exceptionally cruel.

In 1580 the squanderer magnate Gregory Ostik was beheaded, for he aimed to pay his debts by spying for Muscovy. Moreover, he forged documents, seals and counterfeited money. His accomplice died alongside him.

Perhaps the most famous execution to take place in the 17th century Vilnius was the one of Russian duke Danilo Myszecki. During the first occupation of Vilnius (1655-1661) he served as the voivode of the city and earned the fame of being exceptionally cruel. It is possible that the punishment delivered on 10 December 1661 was carried out by Myszecki’s cook, not the city’s executioner.

At the end of the 18th century at least two capital punishments of importance to the state were held. In 1794, during the uprising of the Tadeusz Kościuszko two members of the pro-Russian Targowica Confederation met their end. On 25 April Grand Hetman of Lithuania Szymon Kossakowski was hanged, while on the 9 May Marshall Ignacy Szwykowski stepped on the scaffold.

Aivas Ragauskas