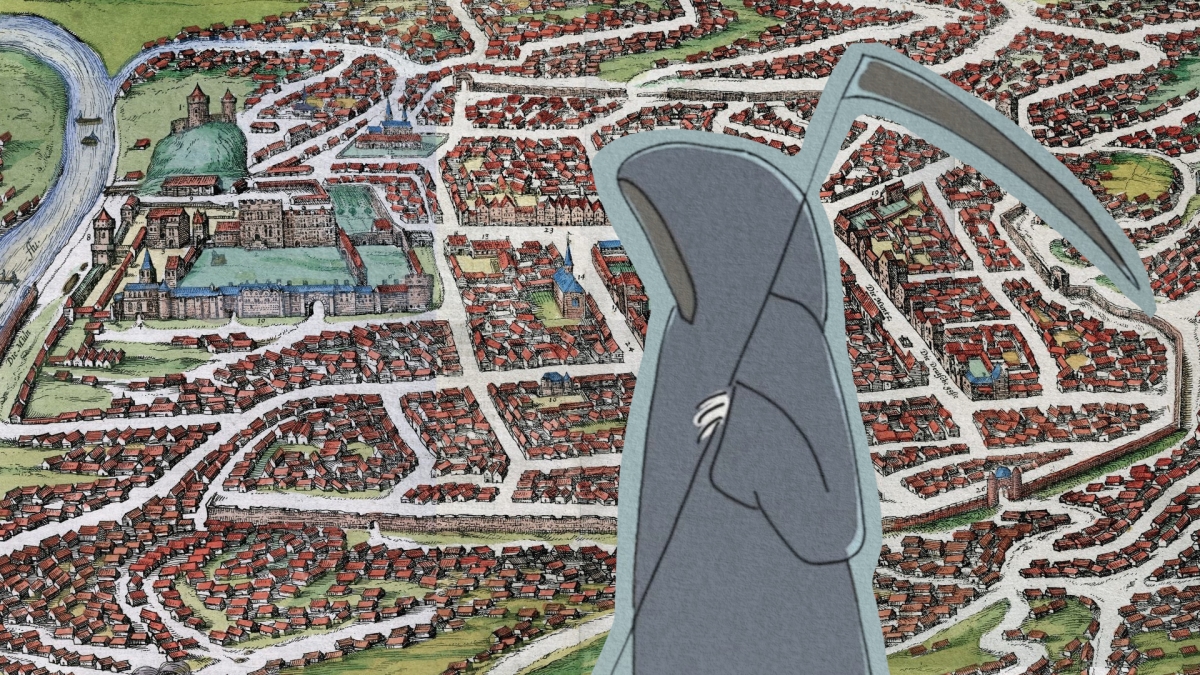

The 1657–1658 Plague and Other Strokes of Fate for Vilnius

It is hard to tell whether the mid-17th century Lithuanians ordinarily prayed to God to spare them from famine, war, fire, and plague. What is certain, though, is that at that time all four calamities struck almost simultaneously, almost as if the evil powers had conspired against the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and its capital Vilnius.

Plague in the occupied city

The plague that broke out in Vilnius at the end of May 1657 and lasted for less than a year, but it could be classified as a pandemic due to its virulence. The malady spread partly because the city was occupied.

“

The plague that broke out in Vilnius at the end of May 1657 and lasted for less than a year, but it could be classified as a pandemic due to its virulence. The malady spread partly because the city was occupied.

The Muscovite forces took Vilnius on 8 August 1655 and plundered it with such ferocity, that the fires lasted over two weeks. Once they ceased and the Muscovite tsar Alexis arrived in Vilnius, he was forced to stay in a tent.

Famine ravaged the city further. Wealthy Vilnans immediately fled the city and settled in its suburbs, moved to Kėdainiai and as far as Königsberg.

Before leaving, Vilnans nailed their windows shut and barred the doors to their homes, shops, and workshops. This did little to repel all kinds of thieves that flooded the city. Muscovite soldiers, local peasants, and destitute Vilnans all sought ways to get inside the abandoned homes. Some valuables were well hidden though, especially those buried underground. Some hideouts were located in private backyards, others on Church land, as it was thought to be the safer alternative.

Every step might be fatal

Literary works often cite rats as primary spreaders of plague. The reality is somewhat different, as Yersinia pestis, the bacterium responsible for plague outbreaks, may be transmitted by many other rodents, domestic pets, and wild animals, such as foxes and ferrets. Ways to catch the plague were several and included flea bites, contact with a body or bodily fluids of an infected person, eating infected meat, and even threading on the infected soil.

Yersinia pestis bacteria cause tissue necrosis.

Do You Know?

The symptoms differ depending on the type of infection. Infection through the skin leads to blisters, puss, that eventually burst and forms a scab. infection by flea bite leads to lymph node inflammation and bubons. If the bacteria enter through the nose or mouth, it damages lungs causing coughing blood. Ingestion of the infected food will result in vomiting and diarrhea in blood. Regardless of the infection type, plague was fatal in the 17th century.

The 1657–1658 pandemic was not the first severe outbreak in Lithuania. Plague strained the country every fifteen or twenty years on the average. People soon realised that there are simple and affordable means to avoid the deadly disease, such as keeping your home and yourself as clean and tidy as possible and limit personal contacts with friends and families. This is why plague eventually became the disease of the very poor, such as homeless beggars and vagrants.

The plague administration

“

The plague administration also appointed 30 guards to patrol the streets day and night to prevent crime. Every guard was paid four złotys a month, the money that would buy two fat pigs back then.

When the plague struck, most municipal officials fled. The city then elected the so-called plague administration led by Vilnius Wójt Józef Kairelewicz. It was responsible for the prevention of street crime and carrying out justice. The officials collected the valuables of the dead and stored them in a dedicated warehouse. Vilnius still had its executioner and a special carter collecting the dead and taking them out of the city.

The plague administration also appointed 30 guards to patrol the streets day and night to prevent crime. Every guard was paid four złotys a month, the money that would buy two fat pigs back then.

Fire smoke for disinfection

To control human movement, the administration installed dozens of well-guarded checkpoints outside the city walls. Only the Rūdininkai gate was left open during the daytime. The keys to the gates were kept in Wójt’s hands. Moreover, close guard was kept along the city walls, so as people would not try to dig under them or breach the wall.

Limitations were strictly adhered to, even foreign envoys were not allowed into the city. At least on paper. Some succeeded to get in through some hole in a wall, others bribed the gatekeepers. people fled the city in hopes that the sustenance was easier outside town.

“

A special procedure of disinfection was introduced. Everyone entering or exiting the Rūdninkai Gate had to get “smoked” for several minutes by standing next to a bonfire. Many people believed that smoke killed the plague bacteria. Even letters sent out of Vilnius had to be treated this way to reduce the risk of spreading the disease. Moreover, those were rewritten several times, so as to minimize the possibility of infection.

A special procedure of disinfection was introduced. Everyone entering or exiting the Rūdninkai Gate had to get “smoked” for several minutes by standing next to a bonfire. Many people believed that smoke killed the plague bacteria. Even letters sent out of Vilnius had to be treated this way to reduce the risk of spreading the disease. Moreover, those were rewritten several times, so as to minimize the possibility of infection. We know that the extant letters sent to Smolensk during this time did undergo such procedures.

City life was paralysed. Markets, shops, and taverns all closed down. The river port ceased operation. The streets and squares were empty, just like many homes.

People were afraid of any direct contact. Even wills had to be drawn up in a special way, the dying person and the scribe separated in different rooms.

Food supply struggled and Vilnans were low on food. Following the widespread European practice of leaving as soon, as far, and for as long as possible, Vilnan physicians left and local residents had barely any access to medical assistance. The sick were left with nothing more than a hope of divine interference.

The Italian method

Hundreds of Vilnius healthy Vilnans gathered inside the St Peter and Paul Church to pray beside the painting of the Blessed Virgin Mary. They knew the picture was painted after a much older original from the town of Faenza (Italy), which, as the legend goes, saved the city of Faenza from plague in 1412.

The painting shows the Holy Mother holding several broken arrows. As the legend goes, she urged the residents of Faenza to fast and asked the local bishop to lead solemn processions thrice a day. “Then I will soothe my son’s wrath just as I have broken these arrows”, she said. And she kept her promise. At least the residents of Faenza believed she had.

The painting still hangs in the Church of St Peter and Paul – the crown jewel of the Lithuanian Baroque. During the year of the plague it was still made of wood. In 1650 Vilnius Bishop Jerzy Tiszkiewicz (1596‒1656) presented the painting to several monks hailing from Faenza living beside the church.

Half the city could have died

The plague raged for roughly a year and although the deaths were many, their precise number remains unknown. In 1658, after the pandemic had subsided, the city’s officials wrote to the Muscovite tsar that Vilnius had lost half of its population. If that is true, up to ten thousand people might have perished, including the interim administrator, Józef Kairelewicz, and one of his scribes, Kaspar Lada.

The pandemic also killed at least one incredibly stupid Russian soldier who stole pants of a dead man, knowing full well he had died of plague. No one will ever explain why the soldier considered the pants worthier than his own life.

By Raimonda Ragauskienė