The Story of the Alembic kept at the Palace of Grand Dukes

Only two or three pharmacies operated in the early 16th-century Vilnius, but that completely sufficed, as the city was fairly small with the population not exceeding 30,000 inhabitants.

Vilnans and city’s guests had access to all key medical services known at the time. The choice of their providers was quite broad, ranging from local wise women, magicians and folk healers, to barbers (many of whom worked as surgeons as well), pharmacists, and university-educated professional physicians.

The choice was limited by one’s means. Pharmacists enjoyed a steady flow of customers.

“Officinae pharmaceutica” since the early 16th century

The first pharmacy in Vilnius opened between 1506 and 1509, the precise date remains unknown. A hundred years later, in the early 17th century, four to six pharmacies operated in the city that were known as officina pharmaceutica and employed a total of 30 pharmacists, including those working for the royal court. Moreover, each pharmacists had at least one assistant.

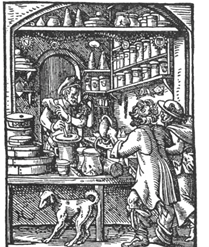

Preliminary medical check was not mandatory, and medication was readily available to all who could afford it. The healthy would shop for alcohol, sweets, and candles. Moreover, pharmacies in 16th century Vilnius offered a wide range of spices (especially Oriental), perfumes, and confectionery. Some of the latter, such as marzipans, were expensive, but people believed in their efficacy to strengthen the organism and aid digestion.

“

Preliminary medical check was not mandatory, and medication was readily available to all who could afford it. The healthy would shop for alcohol, sweets, and candles. Moreover, pharmacies in 16th century Vilnius offered a wide range of spices (especially Oriental), perfumes, and confectionery.

In other words, up until the 18th century pharmacies were somewhat unusual establishments that today would remind us of a mixture between a grocery shop and tavern.

The trade in medication, especially alcohol, was very lucrative. No wonder that the expressions such as “expensive as in a pharmacy” or “pharmacy prices” appeared in those days. All the pharmacists of the 16th-century Vilnius were wealthy and respected people. Some of them became members of the magistrate, others served the magnates, and even the rulers of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.

Sometimes their patrons entrusted them important secrets. Zofia Gasztołd (d. 1549), the wife of the Voivode of Vilnius, entrusted her pharmacist with the secret location of her jewels. When she died, the King Sigismund Augustus and his brother-in-law, Mikołaj Radziwiłł the Red, tried to find out the secret and even had “that meagre pharmacist” imprisoned, but were eventually forced to released him.

Locals, Poles and Germans

Some of the Vilnius pharmacists were Vilnans named Jakub, Sebastian, Jakub Jabłek. Alongside them a number of Poles and Germans worked in the city, including Pasternak, Gambina, Mrzygłód, Konrad etc.

In pursuit of larger profits and greater prestige, they settled their businesses exclusively in the centre of the city, in the vicinity of the Lower Castle and on the present-day Vilnius street, later – in the Pilies, Didžioji, and Vokiečių streets. Several buildings have survived where pharmacies operated in the 16th century: Didžioji St. 6 (Jablka’s), Didžioji St. 8 (Gambina’s) and Pilies St. 20 (Rupert Fink’s).

“

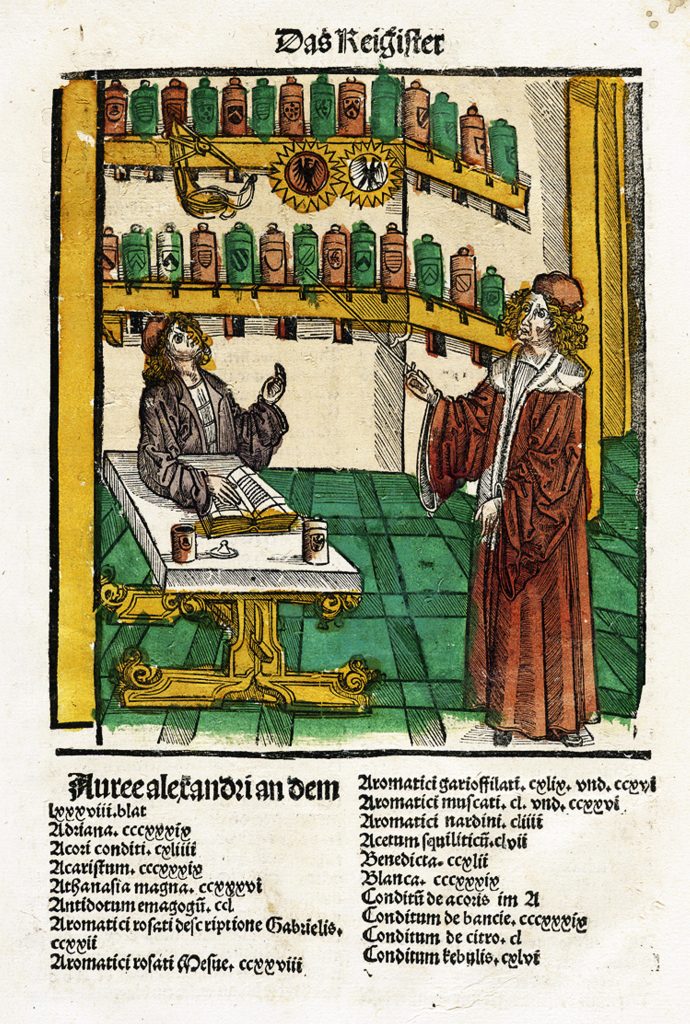

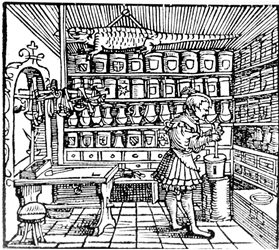

Pharmacies were luxuriously decorated and surrounded with a hint of mystery.

Pharmacies were luxuriously decorated and surrounded with a hint of mystery. The sign that marked their entrance featured pictures of Africans, elephants, and other “exotics.” Once inside, the visitor would find himself in a largely unfamiliar world dominated by strong aromas of herbs, oils, and spices.

The interior enhanced the impression further: mysterious devices and tools, numerous shelves with “materia medica” contained in glass flasks, bottles, ceramic and porcelain vessels, in barrels and boxes. The scales must have stood on the table as an indispensable tool.

Beside the most important room where the customers were served, was a laboratory and several other rooms storing raw materials.

Do You Know?

In terms of product supply, pharmacies in Vilnius did not differ much from those elsewhere in Europe. Some of the medications were old and traditional, their recipes dating back to antiquity , while others were created during the Renaissance. A total of up to seven hundred preparations were known that included materials ranging from exotic, such as snake venom, dog fat and shilajit, to those used everyday, such as rose water and capon broth. The latter was prepared for the weak patients.

Enema for the sick, alembic for the healthy

Capon broth was far from the only peculiar item in a Renaissance pharmacy. Weirdly enough, pharmacists used lead in making plasters and certain medications.

They offered up to 100 types of ointment, most expensive of those being mithridate and theriac that were made of forty to seventy ingredients. People believed both of them could treat a number of ailments. But the most powerful remedy from five centuries ago, a true panacea, is something that many present-day people are still familiar with: the enema. It was used to treat almost every ailment, including toothache.

Every pharmacist was able to distil all kinds of alcoholic beverages, such as vodka, nalewka, and strongly aromatised liqueurs. That’s when he required an alembic, a distillation apparatus present in every pharmacy. Some called it the king of the Renaissance pharmacy.

“

Every pharmacist was able to distil all kinds of alcoholic beverages, such as vodka, nalewka, and strongly aromatised liqueurs.

One such appliance dated to the late 16th century is kept at the Palace of Grand Dukes in Vilnius. It may have belonged to the famous pharmacist and royal physician Rupert Fink, who died in about 1579. He came from Germany and owned one of the largest pharmacies in the city.

There are several famous stories related to Rupert Fink. He, along with his wife and servants, was accused of killing their maid Hana, but was acquitted after swearing “on his honour as a physician and oath to the king.”

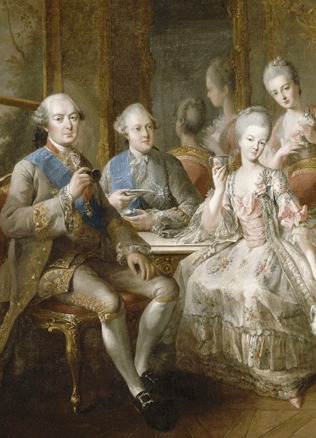

In addition, Fink was responsible for the health of Catherine of Austria (1533–1572), the third wife of Sigismund Augustus while she resided in Vilnius.

According to the contemporaries, on the night Catherine died, an owl flew into her bedroom. On his return home, Fink found the owl perched on his window. Very surprised, he stuffed the bird into the chest, but it disappeared after a while anyway. Fink then said to his wife, “Know that it’s a bad omen related to the death of the Queen, her grace our benefactor.”

In the morning it became clear that the prophecy was true.

Raimonda Ragauskienė