The symbolism of Castrum Doloris: Respecting the Deceased, Preaching to the Living

Castrum doloris, (Lat.: castle of sorrow) was one of the key elements of the Baroque funeral. The memorial service for noble people would be organised as a public event at that time. To make an impact on spectators’ imagination, a wide array of visual and verbal instruments were used, including funeral speeches during processions, streets and buildings in funeral decorations, refurbishment of churches by means of drapery and illumination in order to create an exclusive space for the one lying in repose. Castrum doloris was an ornate catafalque usually built in the centre of a church where the most important funeral ceremonies were held. Its decoration was meant to convey, in symbolic forms, the main themes of the parting ritual.

Heraldry of the otherworld

Do You Know?

The “castle of sorrow” consisted of baldachins, pyramids, obelisks, statues of saints, personifications, heraldic figurines, portraits, and inscriptions. Individual parts of the construction were meant to produce a complex visual tongue that combined at least three motives, that of the deceased seen as an example to the living, of homage to the noble family, and of mourning.

Aristocratic blood was the most important element deserving praise during the ceremony, while the coat of arms, the key sign of nobleness of the deceased was the main motive of the castrum doloris.

Figures of family patron saints would hold the coat of arms of the deceased, while heraldic elements were meant to reflect his or her virtues or symbolise the deceased or his or her broader family. For example, the castrum doloris erected in 1731 inside the Church of the Holy Spirit in Vilnius for the funeral of Ważinski, a bailiff of the town of Viešvėnai, featured a figure of the Archangel Michael, the patron saint of the deceased, as the main focus. The saint held the W-shaped emblematic sign, the Habdanka, turned by an artist into scales with the symbol of the eternity in its one pan and the insignias of the deceased in the other. The decoration of the Kościesza, the coat of arms of Jaronim Żaba, featured two arrows, one of which, pierced through a heart, reflected his widow’s sorrow, while the other, fluttering high above the clouds, symbolised parting with earthly life during his funeral in 1765 in the town of Alshyany.

The embodiment of virtues

The deceased was supposed to serve an example of virtues to all living humans. The main Christian virtues, such as wisdom, temperance, righteousness, and sturdiness, were usually personified through female images bearing respective attributes. The wisdom would hold a sword and scales, temperance would have the bridles, the righteousness would hold a serpent and a mirror. The entire structure was meant to underline piety, mercifulness and generosity of the deceased. The decorations used for the funeral of Izabela Katerzyna Oginska, the wife of the castellan of Trakai, included the figure of the generosity described the following way by eyewitnesses: “The figure on the right side of the catafalque held a portrait of the duchess in one hand and was dispensing valuable items and money to the needy with its other hand. The figure of Time, with a clepsydra on her head, stood on the left side holding a scythe and a tombstone in her hands”.

Do You Know?

The social status of the deceased was considered very important and was to be praised during funeral. Occasional pieces of literature would emphasise his or her place in the ranks of the society as the evidence of the person’s generosity which, just like the noble blood, were seen as signs of good luck. A catafalque and the entire church would be decorated with the insignias of the deceased that, again, were meant to underline his or her position within the society. A number of such items surrounded the catafalque of Stanisław Denhoff, the Field Hetman of the GDL and the voivode of Polotsk, including hetman’s cap, mace and staff, his personal panoply, several swords, a shield and the Order of the White Eagle.

The deceased was expected to have lived working for the benefit of the state and of the Church to earn eternal glory.

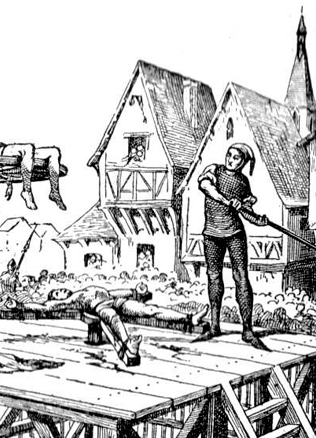

That is why traditional funeral decorations often included military symbols and even allusions to ancient heroes – all that to reveal the merits of the deceased as a defender of his fatherland. The castrum doloris of Jan Feliks Sziszka, the standard-carrier of the GDL army, was decorated with a number of columns topped with figures holding weapons and a standard. His catafalque was surrounded by six sculptures of six knights holding heads of dead men symbolising the enemies he has defeated. Other symbols and inscriptions were used to reflect the deceased person’s support of the Church. The funeral of the aforementioned Ważinski featured the sculpture of the Holy Virgin Mary crowned with a chaplet of roses and with three roses in her hand reminding of the funding of the St. Rosary Church in Ashmyany by the deceased. The sculpture of Faith stood nearby accompanied by the list of all churches throughout the Polish and Lithuanian Commonwealth the building of which the bailiff had fully or partially funded.

Elaborate setting for funerals

The motives of grief and loss were no less important than the symbols reflecting merits of the deceased and his family. Over the three days of the last farewell ceremonies, the structure of the catafalque would change several times; in the beginning, the main motive would be blessing of the deceased, while towards the end the victory of death would emerge as the main symbol. The second day of Sziszka’s funeral saw the portrait of the deceased removed from the top of the catafalque. The portrait was placed on the floor with a painting of a falling column and coats of arms of the state above it. On the third day, an earthen grave inside the church replaced the pedestal for the castrum doloris with a simple cross on it and an allegorical painting of death holding a spade at the feet of the deceased.

Such changes of funeral decorations were meant both to console the family of the deceased and, together with other religious items, to perform a didactic function of reminding friends and relatives that during the time of mourning they should contemplate about death, the Last Judgement and the salvation of their own souls.

In some instances, the family would obey the last will of the deceased who had asked for a modest funeral – but only on the last day of the ceremony. In such cases, the third day would see a simple coffin replacing the splendid catafalque and all the elaborate illumination removed. Jan Michal Strutinski, the founder of the Discalced Carmelite Monastery in the town of Antalieptė, wore a monk’s robe on the third day of his funeral following his own will.

The importance of castrum doloris has been revealed through a multitude of its descriptions and images. Just like other kinds of occasional production in the Baroque era, the “castles of sorrow” used to bring together words, images, and secular and spiritual motives. The lavish construction built for a particular funeral served as an important instrument of representation. At the same time, it performed emotional and didactical functions.

Lina Balaišytė