The Collapse of the Vilnius Town Hall Tower

It happened on 19 June 1781: the tower of the City Hall in Vilnius crumbled into a pile of bricks and stone.

Towers were part of many European Town Halls. Usually they housed the main clock, but the tower itself was not insignificant and municipal officers aimed to build it as tall and ornate as possible.

The six centuries of Vilnius Town Hall

Do You Know?

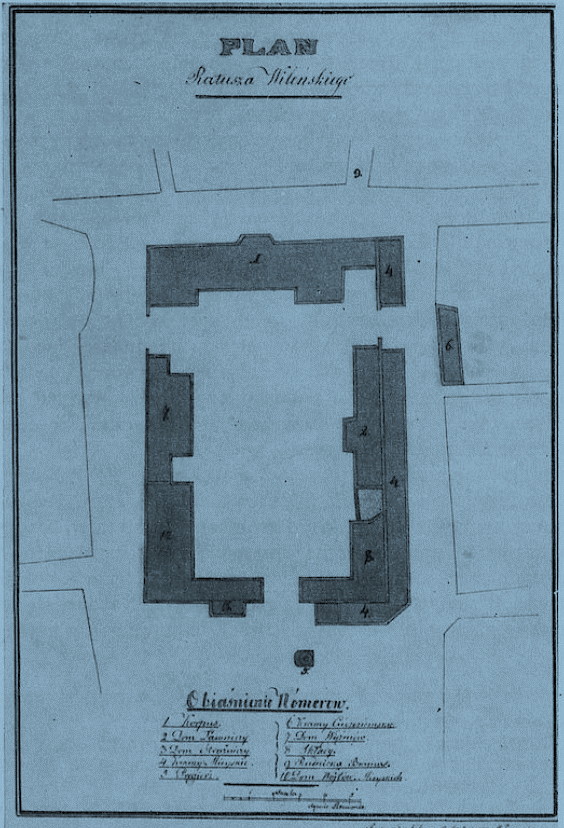

The tower and the Town Hall were erected in the middle of the 15th century, both rendered in the Gothic style. We find images of a masonry tower, topped with a wooden spire covered in copper plates, in the 16th-17th century sources. During public festivals the tower, just as the Town Hall, was illuminated and accommodated musicians, who would play long into the night.

On 8 June 1749 fire devastated the tower and the Town Hall. Just ten days later, the magistracy signed a contract with a German architect, Johann Christoph Glaubitz (ca. 1715–1767), charging him to rebuild the tower following the city-authorised project. The architect had to procure the materials and hire workers, while the magistracy supplied the copper plates for the spire.

The reconstruction ended in 1769, but eleven years later, in August 1780, the tower barely avoided repeated destruction, once fire broke out in the neighbouring Vokiečių [German] Street. The tower was left unscathed due to the suddenly calmed wind. Despite the happy ending, its days were numbered.

The slowly reclining tower

In the years prior to the collapse, people noticed that the new three-storey tower was slowly leaning, but no urgent measures were taken.

Eventually, Burgomaster Leonard Paszkiewicz summoned the architects. Many of them agreed that the tower had to be torn down, their opinions differed only in regard to the manner of destruction: some suggested dismantling the tower by hand, others – demolishing it by cannon fire. However, the municipal authorities rejected both options, for they were concerned about additional spendings.

“

During that meeting architects claimed that the tower is leaning toward Vokiečių Street by 1.7 metres. The famous Tower of Pisa leans by as much as 5.5 metres.

During that meeting architects claimed that the tower is leaning toward Vokiečių Street by 1.7 metres. The famous Tower of Pisa leans by as much as 5.5 metres.

A text from 1781 provides a detailed description of the tower. Its base was a square of 19.52 metre at each side and the tower was nearly 44-metre tall. Below its copper-plated spire the tower housed two bells and was topped by a gilded weathervane.

The tower stood on a 1.3-metre-thick footing, yet it was built on a sandy ground and disconnected from the foundation of the Town Hall. The base was strong enough for a wooden tower, but not suitable to support a larger structure. Despite that, Glaubitz built three storeys of octagonal masonry on them.

Mission impossible

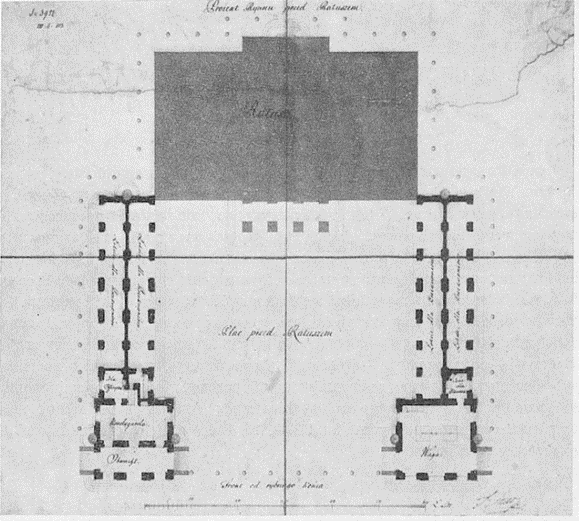

Soon after the magistrate realised that the tower was about to collapse, architect Laurynas Gucevičius (1753–1798) suggested straightening the tower and reinforcing its understructure.

On Monday, 9 June 1781, the work commenced by hanging a counterweight on the ground floor and digging at the foundation from the side of Vokiečių Street. The base was strengthened by adding a six-foot-tall and four-foot-wide masonry supports. Moreover, a nine-foot-tall counterweight was built there together with new segments of the foundation on the other side.

Unfortunately, the week-long effort resulted in the crumbling of a large interior wall, soon followed by the collapse of the side wall supporting the tower. Its leaning accelerating by the hour, the tower fell on 19 June at about 3.30PM. Many sceptics deemed this outcome inevitable.

“

Things went wrong. In theory, Gucevičius’s plan could rescue the tower, yet the structure proved too weak.

Before condemning Gucevičius’s plan to rescue the tower, it is well worth considering that in the late 1990s the Leaning Tower of Pisa underwent a similar procedure. The tower stopped leaning, moreover, went back by about 40 centimetres, when around 100 kilograms of ground beneath it was dug out daily. In Vilnius, however, things went wrong. In theory, Gucevičius’s plan could rescue the tower, yet the structure proved too weak.

Advocates of conspiracy theories maintain that Gucevičius was instrumental in the demise of the tower, as it gave him the opportunity to build yet another of his “neoclassical boxes” in the Baroque Vilnius. Writing in 1781 theologian Wojciech Bagiński described Gucevičius as a “flippant”, who dug under the tower’s foundation first and then “barely managed to escape the pit and the city itself.”

No tower for the new Town Hall

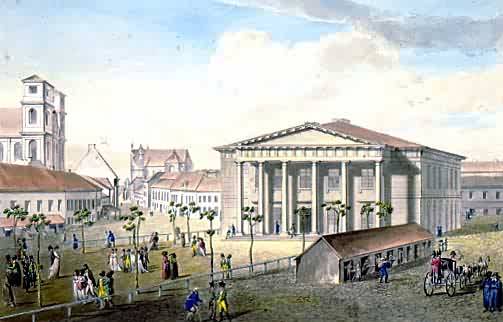

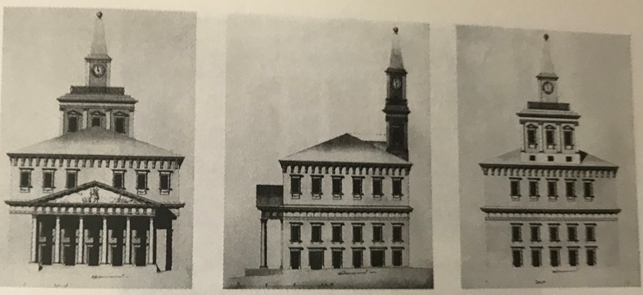

Eventually it was Gucevičius who was granted the honour to design the new Town Hall. The magistrate chose the project without a tower, although several rival designs featured it.

The current neoclassical building was erected in the late 18th century. Some experts call it a masterpiece of architecture and insist that the edifice, its concept based on Greek and Roman temples, constitutes one of the most innovative solutions of the 18th-century neoclassicism and adds to the image of Vilnius as a modern city.

According to one of them, the Vilnius Town Hall is unique in the context of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and “perhaps the whole of Europe”. The project embodies the main concept of Gucevičius style. It holds that beauty, harmony, and greatness should be “expressed through the harmony of parts and their relation to the whole, rather than by embellishments.”

Some experts hold completely opposite opinions. Some contemporary historians claimed that the fact that the Baroque building had been replaced by the neoclassical one speaks of a drastic loss of the city’s identity, the new Town Hall being an “edifice without history”. It bears no similarity to the old municipal government that was symbolized by a clock tower and a whipping post.

Aivas Ragauskas