The Collapsed Floor of the Supreme Court

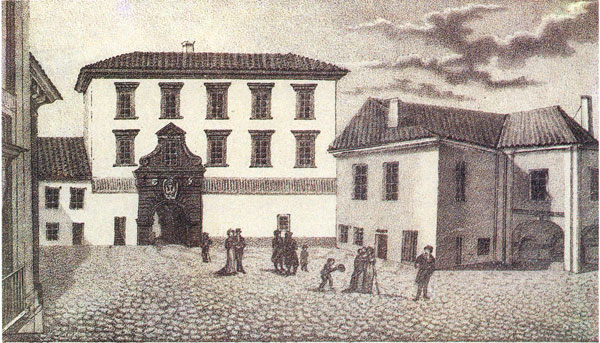

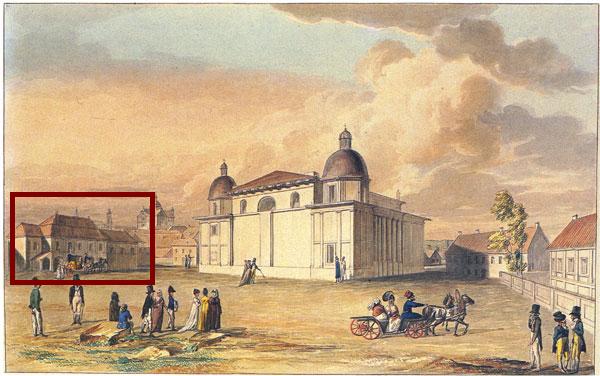

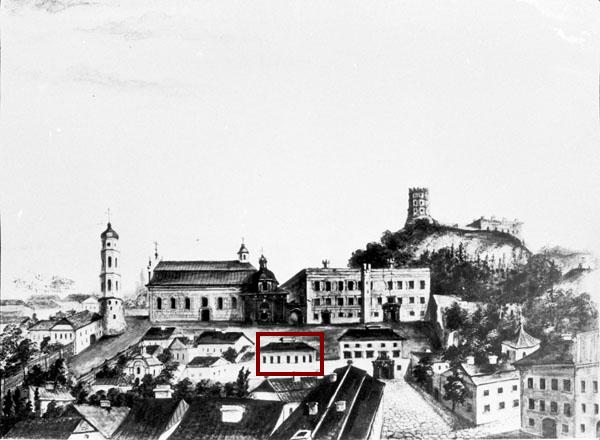

The Lithuanian Tribunal was the highest court of appeal for the nobility of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. This substantial, reliable institution was established in 1581 by the order of the King Stephen Báthory, its headquarters in the heart of Vilnius, just a few hundred metres from the belfry of the Cathedral.

More than three centuries ago, on a beautiful spring day, the Tribunal witnessed an incident that nowadays would undoubtedly make breaking news across Lithuania.

The event through the eyes of a witness

“On Wednesday prior to the Ascension Day, 5 May 1655, at midday, half past noon, once the litigants left the courtroom so that the judges of the Tribunal could deliberate over the court ruling, the courtroom lobby, full of people of all estates, collapsed. Neither was I able to escape the calamity. Shortly before that, my servant Samuel Rotkiewicz, who had been observing the hearings inside the tribunal, sent me a message, saying that according to the list my case would be heard shortly. I abandoned my lunch and hurried to the castle; as soon as I entered the lobby, I saw several all-powerful gentlemen talking in the middle of the hallway: Aleksandrowicz, the deputy judge of Ashmyany; Aleksandr Wróblewski, the master of the horse of Trakai; and Michał Poniatowski, the cup-bearer of Mazyr. As soon as I approached and greeted them, at that very moment, the lobby floor collapsed with all of us.

“

At midday, half past noon, once the litigants left the courtroom so that the judges of the Tribunal could deliberate over the court ruling, the courtroom lobby, full of people of all estates, collapsed.

Those seated around the lobby or standing by its stone walls also fell, indeed, right on us, who were standing in the middle. Therefore, we found ourselves buried under the remnants of the parquet floor, bricks, dirt, as well as people lying over us, hence it took a great effort (that lasted for about a quarter of an hour) before we could stand up and were pulled out, as the people above us pressed us down to the extent we nearly suffocated. I was standing on the bottom on my left foot, while the right one was sprained horribly to the side, and since it hurt badly, I thought to myself: “it must be broken.” While they were frying me, they were only able to do so by great effort and pain, as I felt so powerless, that they had to pull me out as if pulling out a screw, yet due to God’s grace and divine providence, I had, apart from intense pain, no other bruises or other marks on my body, for this may the Lord be forever adored.”

Under the lobby the Muscovites were held captive, yet, fortunately for them, they were let outside to get some sunshine just before the accident. Some of them stayed inside and stood beside the walls, so nothing happened to them. The beams collapsed in the middle, but their ends remained inside the walls, therefore nothing happened to those under the lobby, sitting above it, or standing by the walls. The fall did not cause fatal injuries, yet it hurt and bloodied many.”

When did Baroque men experienced climax?

After describing the disaster at the Tribunal, Maciej Vorbeck-Lettow finds its cause upon reflection: “On 12 February of that year, my climacteric year began.” Thus, was called the disastrous year affiliated with the number 7.

Do You Know?

Astrologers held that the 63rd year of life was the most dangerous for everyone, as it brought death or great misfortune.

Vorbeck-Lettow continues: “My 63rd year, a miserable year for every person, as various authors write. It seems, these will be just as unfortunate to me, because I often feel low due to ill health and my personal attitude toward the aforementioned incident. Unsure of its ultimate meaning, I maintain that only God is aware of its significance, may his sacred will be done, my own will obeys it.”

Notes of a notable Vilnan

We know all this from “The Treasure of Memory”, a diary written by Maciej Vorbeck-Lettow (1593–1663), a Vilnius-based physician and municipal officer. He was one of the most famous Vilnans of the 17th century and his diary is a unique source of information, the only known 17th-century autobiographical text written by an urban dweller. The diary provides valuable data on his family and kinship, interpersonal relations, mentality, and author’s daily life. Even a brief passage quoted above reveals a number of details of the time, from standing in line for court proceedings to trying to comprehend the world through numbers.

The translation of the excerpt from the diary into Lithuanian appears in “Maskvėnų okupacijos (1655–1661 m.) Vilniuje kronika: 1665 m.” (Chronicle of the Muscovite Occupation (1655–1661) of Vilnius: 1665) compiled by Elmantas Meilus. It was published in the second volume of “Pasakojimai apie Vilnių ir vilniečius” (Tales about Vilnius and Vilnans) edited by Zita Medišauskienė and published by the Lithuanian Institute of History in 2019 in Vilnius.

Povilas Andrius Stepavičius