The River Port in the Old Vilnius

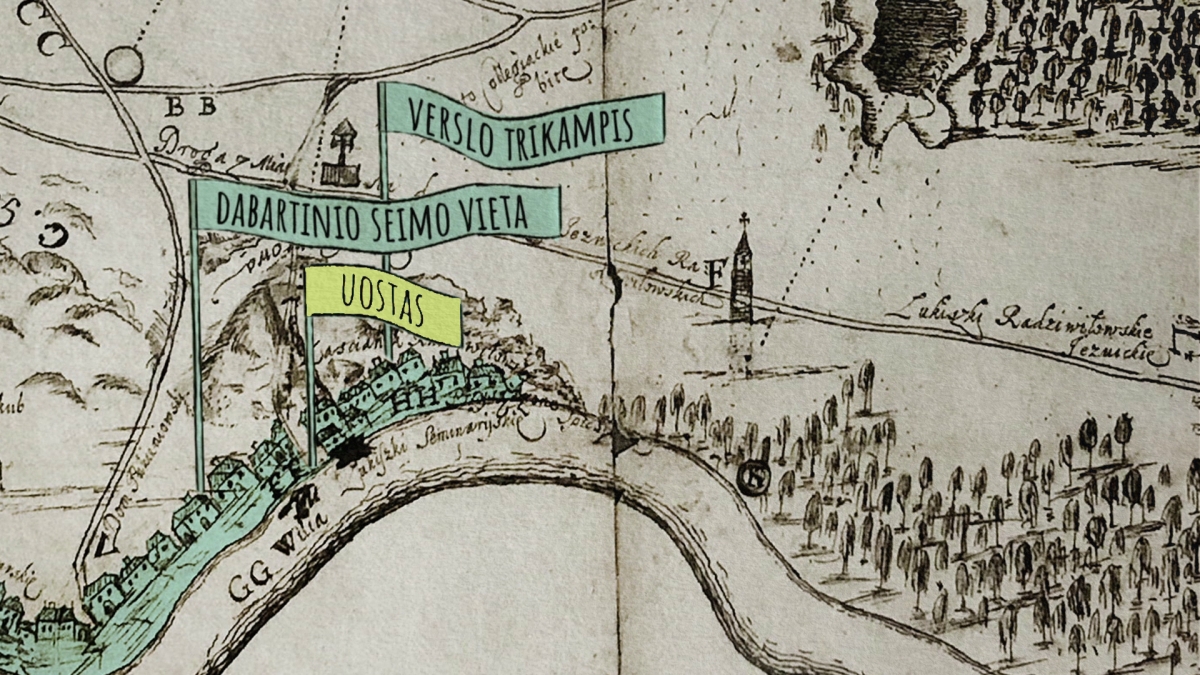

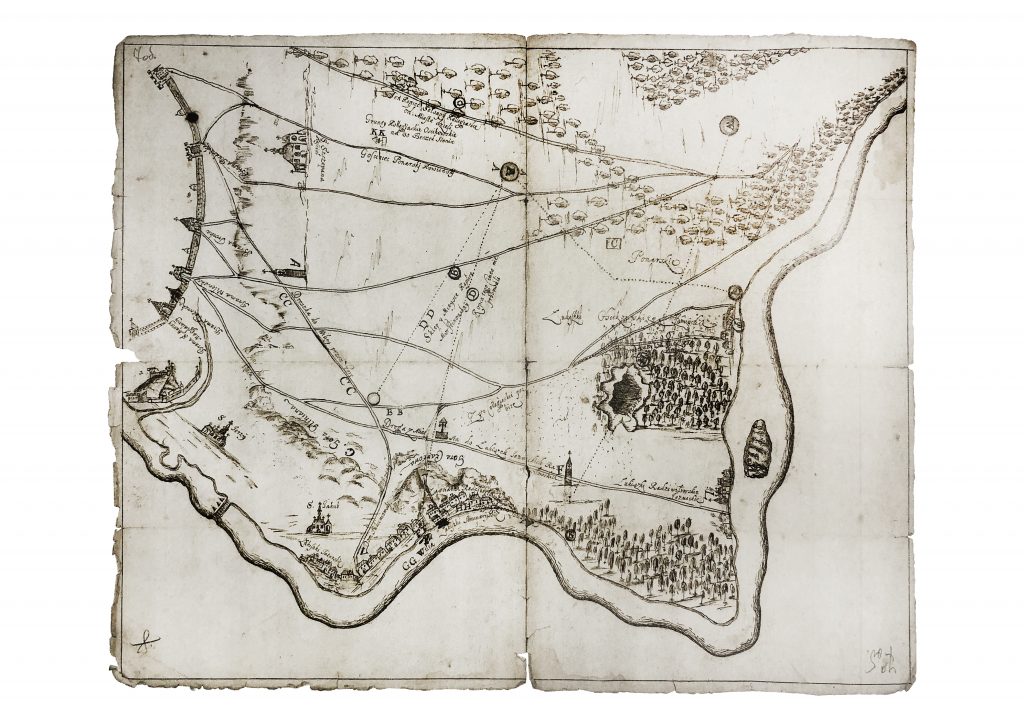

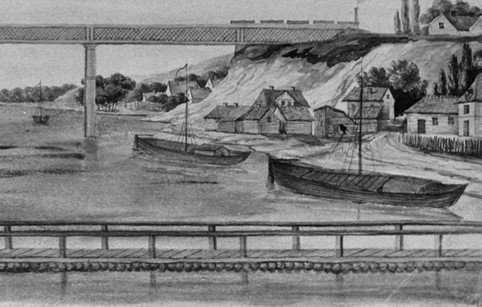

For at least three centuries, until the 1850s, Vilnius had a port where the buildings of parliament now stand. The port facilities were quite simple, consisting of wooden quays by the water and wooden storehouses on the riverbank. Come spring and every year the swollen river would damage or completely destroy the quays, this being the main reason why underwater archaeologists have not found any sign of the port there. Other data about it is rather scarce too.

Rivers, the arteries of trade

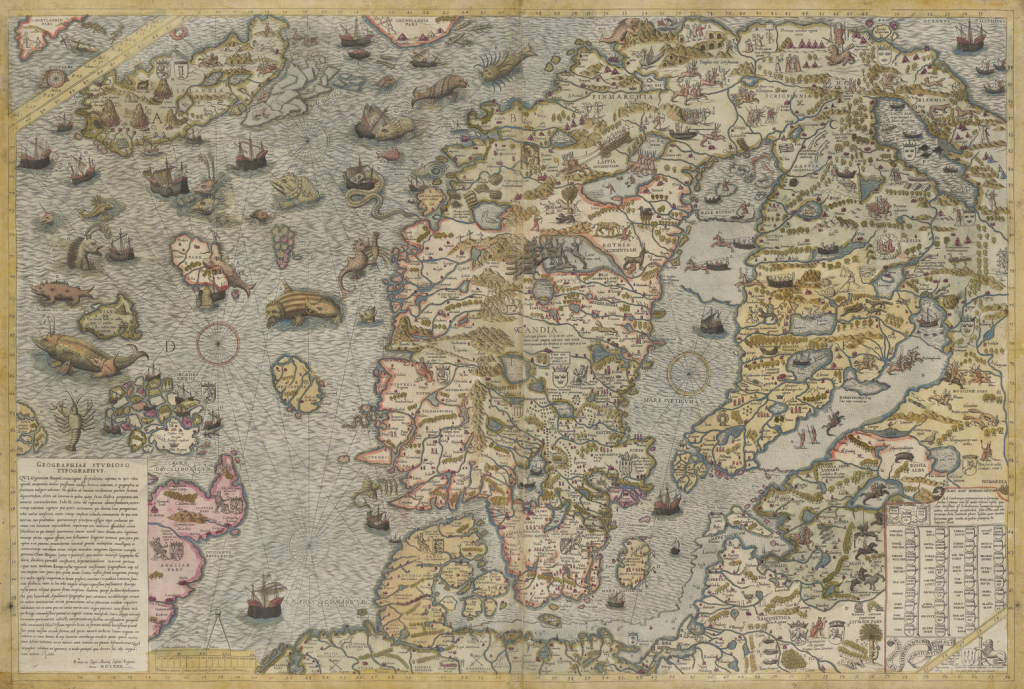

For many centuries, river shipping was the most efficient way of commercial transport. Merchants’ interest in ships and rafts showed no sign of subsiding until the middle of the 19th century, when rail transport began taking hold. River shipping was the cheapest option for any large shipment of goods, be it grain, timber, salt, herring, wine, metals, or anything else.

However, fluvial transportation was complicated: rivers freeze during winter and recede during summer. Moreover, travel upstream was slow and costly because ships had to be towed by men. River trade routes were limited due to the lack of canals connecting major waterways. In the former lands of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania most canals were dug as late as at the turn of the 19th century.

“

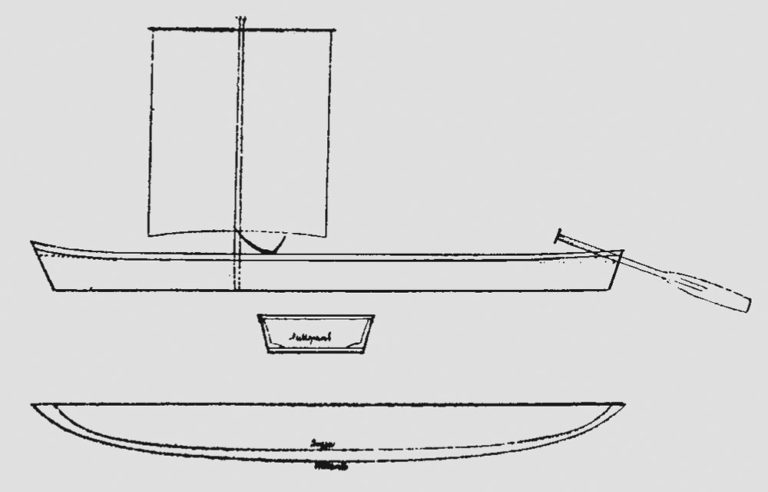

Vytinė was the name of the most popular river ship in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.

However, rivers were extremely important because land roads and bridges were very scarce too. Come spring or autumn and rain would render them unusable. On the other hand, land travel incurred greater customs tax for merchants.

Vytinė was the name of the most popular river ship in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. They still sailed River Neris in the late 18th century. A vytinė could reach up to 30 metres in length, 1.5 metres in height and carry up to 25 tonnes of cargo, just as much as a modern truck.

Other vessels used in river trade between Vilnius and other cities included strugs (still seen sailing in 1832), barcas and semi-barcas, Prussian boats, Berlin boats and small boats called laibas.

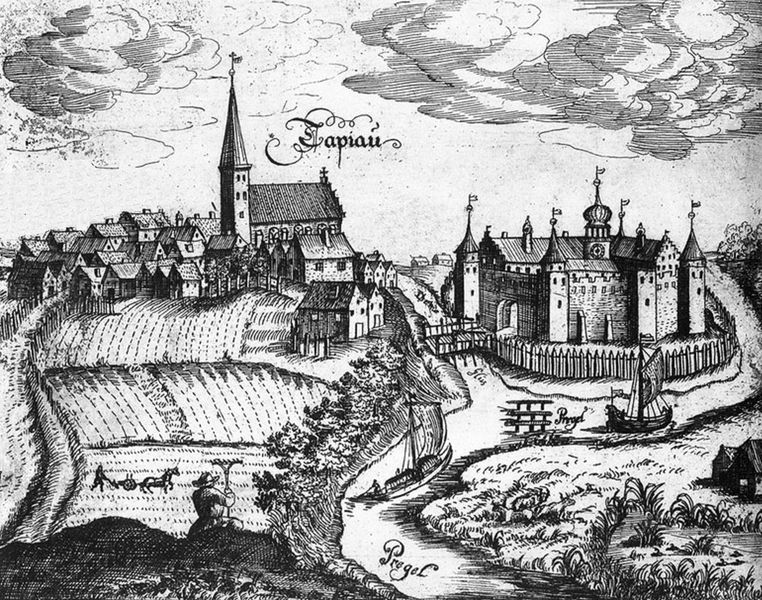

Ships sailing from Vilnius would reach faraway lands, including Königsberg, Tilsit, and other cities in what was then Prussia.

The four centuries of the port

The river port in Vilnius operated from the early 16th century, always occupying the same territory. Several dozen warehouses were built on the riverbank to store goods and parts of ships’ rigging, such as sails, ropes and anchors.

“

The river port in Vilnius operated from the early 16th century, always occupying the same territory.

All the warehouses were made of wood, though some had stone cellars and some were built as two-storey houses. Each warehouse, occupying a piece of private land and surrounded by a fence, stood on a stone foundation. The richest merchants operated up to eight warehouses, some of them known to have stood in Lukiškės as late as in the 1840s.

Traders stored a variety of goods (most of them in oak barrels) in their warehouses, including flax and hemp seeds, fibre and oil, leather, wood planks, hops, salt, herring etc.

Do You Know?

Only once in its long history did the port stop operating, it was the period from August of 1655 to the summer of 1656. The reason for it was the first occupation of Vilnius. Five years later, in the summer of 1660, during their retreat from the city, Muscovites burned the port down and many ships and warehouses perished in flames.

More than half a year of busy days and nights

The shipping season usually extended over eight or nine months, lasting from March until November. Historical records tell us of a number of climatic anomalies in Vilnius, such as unusually warm winter of 1734, when Neris did not freeze over until 23 January 1735, and a sudden spell of cold that covered the river in thick ice almost overnight on 20 December 1756 destroying wine and other goods vulnerable to the cold.

“

As soon as the river receded, all merchants urged their ships to sail immediately. Time was of the essence, since the earlier the goods reached Königsberg or Tilsit, the higher their price was. Those arriving late usually sold their goods at least two times cheaper than the early birds.

The last day of January 1786 saw the river burst its banks after a week and a half of heavy rain, taking several ships downstream and damaging many more. Many ships were rendered unfit for sailing and proper river trade only began in mid-April.

According to the archival documents, the river was 1.6-kilometre wide in Vilnius, its waters gushing six metres higher than normal in some of the years between 1828 and 1845.

As soon as the river receded, all merchants urged their ships to sail immediately. Time was of the essence, since the earlier the goods reached Königsberg or Tilsit, the higher their price was. Those arriving late usually sold their goods at least two times cheaper than the early birds.

Grain was one of the key commodities shipped from Vilnius. The largest grain shipments went downstream in spring while the water was still high and could carry heavily-loaded ships.

The brotherhood of river-farers

The river-farers, from captains to ship-haulers, known as burlaks, was a motley crew. Some were serfs, others free citizens. Some went downstream and upstream regularly, others occasionally. River-faring wasn’t a very well-paid job, particularly due to long winter breaks. Despite that, those wishing to live “on water” usually outnumbered job vacancies.

“

In 1690 the river-farers established the Brotherhood of St Hyacinth in Vilnius affiliated with the Church of St Apostles Philip and Jacob. It is unclear when it ceased to exist.

In 1690 the river-farers established the Brotherhood of St Hyacinth in Vilnius affiliated with the Church of St Apostles Philip and Jacob. It is unclear when it ceased to exist. However, we know that the brotherhood funded a chapel and an altar dedicated to St Hyacinth in the early 18th century.

The statute of the brotherhood features a number of religious instructions, one of which obliges every river-farer to pray, make a confession, and take Communion before each travel. It also states that captains should only employ people able to swim as crew members.

The river-farers lived and worked under the patronage of Saint Barbara. In old pictures she appears holding three attributes, a goblet, a wafer, and a tower or a palm tree. A thick rope used to drag the ship off the shallows was called barbara, perhaps as a symbol of hope.

A simple everyday life

“

Truth be told, most of the time they had to contend themselves with beer around one percent strong. However, often there were stronger drinks on board as well, such as mead or vodka.

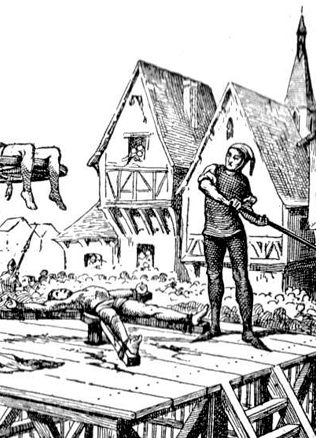

A medium-sized vytinė accommodated up to eighteen crew members, whose everyday toil included anything from loading and unloading, to oaring and hauling. Larger ships usually employed a cook, who had a small wood-burning stove at his disposition to bake bread, boil porridge and fish soup, serve cheese and pork fat while downing innumerable quantities of beer, their drink of choice. Truth be told, most of the time they had to contend themselves with beer around one percent strong. However, often there were stronger drinks on board as well, such as mead or vodka. Their days began and ended with a prayer. The men stuck to the ritual partly because shipping up and down Neris was a dangerous affair. In his book “Neris and its Banks” published in 1871, Konstanty Tyszkiewicz lists as many as 39 rapids, twelve of which were considered particularly dangerous. Large boulders posed significant risks too; the book tells of 48 huge rocks or their groups.

A captain mostly used Polish terms to give orders. He shouted “na stos” when he wanted the ship to turn right and “na giegnie” to turn it left. “Pa treli” meant towing the ship while walking on the bank, “w pole” meant towing toward the middle of the river, while “szybuj” was the word for pushing the ship.

Chest of gold or beggar’s sack

Many river-faring merchants accumulated great riches, but it took just a single mishap to lose almost everything, one such example being Eustachius Szperkowicz, the royal secretary and the Burgomaster of Vilnius. He traded with Königsberg by sending off shiploads of salt and other goods regularly. Everything went well until 1674, when his vytinė sank in the vicinity of Tilsit. A large number of creditors demanded their money back and rushed to his home immediately. The court, in turn, confirmed Eustachius owed a total of 65,000 złotys, a huge sum at the time. The hapless merchant later tried usury as a means of living but died in poverty. The only thing his son inherited was a brick house.

Aivas Ragauskas