Trade in captives – a source of income

An evergrowing number of slaves in recent years shows that the statements of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights about a ban on slavery and human trafficking might turn into empty words unless such phenomena is met with a stronger resistance. The fact that at the present time many people of the civilised world enjoy freedom is a recent achievement, a partial victory against one of the most unpleasant and oldest institutions – slavery. It was known on all the continents (with the exception of Australia) among both primitive and civilised nations.

Millions of lives sold

The essence of slavery is ownership of man by a slave-owner. The essential feature of a slave is the fact that s/he is deprived of all the rights. The condition of a slave is aptly defined by the metaphor of “social death”. Uprooted from the native environment, having lost all family relations and property, a slave became a tool of satisfying the will and whims of the slave-owner. First of all, slaves were assessed as free work force. Economy of Antique Greece and Rome was based on work of the slaves to a great extent; the Carolingian Empire provided itself with slaves from the raids against the pagan German or Slavic lands. However, the first world economic system based on serfdom that is known in World history formed at the same time with the Muslim expansion that started in the 7th century.

The Muslim Caliphate created by conquering foreign countries could survive only by subjugating a large number of people.

In the 8th century, after the Muslim Caliphate had expanded from Spain to India, peripheral lands had to meet the insatiable demand for slaves. The demand was enormous therefore trade in slaves covered Europe, Africa, Middle Asia and India. The Scandinavian Vikings (in the 9th–11th centuries), Hungarians (in the 10th century), the Muslim pirates (in the 9th– 11th centuries) became main suppliers of slaves to Europe.

African states, which were created on the northern and eastern coasts, became slave hunting and export organisations. Statistical calculations show that from the year 650 to 1920 more than 17 million people were deported from Africa to the Muslim lands as slaves; this figure is larger than the number of slaves carried to the Western hemisphere – about 11.5 million (1450 – 1870). Having added at least several million slaves that got into the hands of the Muslims from the Black Sea region, Middle Asia and India, it becomes clear that scopes of this system were really tremendous.

In the 9th century the Baltic lands were also in the slave supply zone.

From then on, the invasions of the Vikings into the Baltic lands allow the supposition to be made that they carried out slave hunting operations there. The Daugava River became a transit channel of trade in slaves. This trade affected the local tribes too. From this point of view, the following fragment of the statement made by the Anglo-Saxon traveller Wulfstan about the Prussia when he visited the lower reaches of the Vistula River deserves mention: “there are many wars between them”. In this way slaves used to appear: some part of them remained in the hands of the local nobility, and another part was realised in the international networks of trafficking in human beings.

Hunt for captives

The Lithuanians who began plundering at the end of the 12th century acted as slave hunters. As is characteristic of other regions engaged in slave hunting, the marches of aggression were notorious for extreme cruelty. During the time of attacks on one another, the Baltic tribes killed men of the other tribe, and mainly took women and children prisoners. It was easier to subjugate these captives.

Do You Know?

African states, which were created on the northern and eastern coasts, became slave hunting and export organisations. Statistical calculations show that from the year 650 to 1920 more than 17 million people were deported from Africa to the Muslim lands as slaves. At the end of the 12th century, the Lithuanians who started marches of aggression became engaged in international trade in slaves. Trafficking in human beings was an important source of income of the grand Dukes of Lithuania.

German, Russian, Polish sources centuries contain abundant information about Lithuanians enslaving local inhabitants. For example, in 1205, the Lithuanians, having devastated the entire region of Estonia, were on the way home “with lots of captives and the innumerable number of seized animals and horses.” Henry of Latvia wrote that more than a thousand Estonians were taken prisoner at that time. Knowing that the Lithuanian troops consisted of about 2 000 cavalrymen, this booty can be regarded as not an insignificant success. Nonetheless, the goods were lost, because on their way back the Lithuanians unsuccessfully encountered Germans and Semigallians. A platoon consisting of one and a half thousand Lithuanians became notorious for its extreme cruelty, which invaded the Sáaremàa Islands: “Stupefied by their own courage / They crossed the whole of the country (…) All the roads, as well as paths / They liberally spattered with blood (…) / They taught people to die, / Both women and men, / If they failed to escape in time.” The invaders did not forget that the most important thing was the booty: “Oxen, horses, women and men / They drove them away with pride”. It is true, they did not reach Lithuania because later the Germans had rallied the Latvians and the Livians and the Lithuanians exhausted after the ride, were easily emaciated: “They found death there. They were struck and wounded / and were not difficult to get the better of.” However, such defeats did not alter the willingness to plunder. Even after the Russian princes beat some of the Lithuanian armies, others appeared some time later. This intensity of the Lithuanian attacks can be compared with the attacks of the nomads from the steppes of the Black Sea Region for which the “life inventory” was the most important things after they had invaded the lands of eastern Slavs and Finno-Ugrians who led a settled way of life.

“Trade” between Lithuanians and the Brothers of the Cross

The establishment of Germans in the Baltics and the marches into the lands of the Lithuanians that started at the end of the 13th century showed that the epidemic of slave hunting reached Lithuania too. Those crusader raids to Lithuania and the raids of the Lithuanians to Prussia or Poland are perceived as campaigns of providing themselves with slaves. Between 1277 and 1376, there were 24 larger marches of the Lithuanians to Prussia and the Polish lands whose main aim was to capture slaves. The Teutonic Order made even a greater number of smaller and larger marches by attacking both from the side of Prussia and Livonia.

Despite confrontation, enterprising Lithuanians and Germans agreed on mutual benefit.

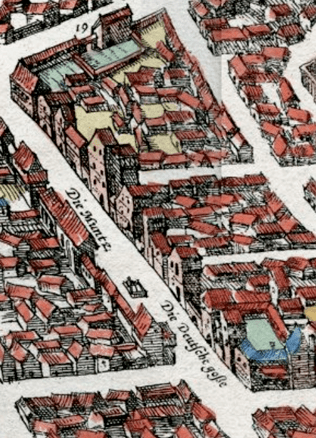

From this point of view the complaint of the residents of Riga of the 14th century about the troubles that one town dweller experienced when he tried to provide himself with the “saleable goods” from the Lithuanian army located near Vitebsk, is worth mentioning: “He wanted to go near the army and buy some girls…Then, going along the road he lost his way and found himself near the monastery. Three monks, and another, fourth man jumped out of it and started beating and robbing him.”

Trafficking in human beings was an important source of income of the Grand Dukes of Lithuania.

This is clearly testified to by a reproach of the Grand Master of the Teutonic Order Conrad Zöllner von Rothenstein to Władysław II Jagiełło that the latter sold the subordinates of the Order to the Russians instead of setting them free as he had promised (1383).

The contribution of pagan Lithuanians to international trafficking in human beings was insignificant as compared to that of the Romans, Arabs, the Vikings or the Crimean Tartars (15th–18th centuries), however, it has been a scarcely noticed and assessed phenomena thus far.

Literature: Lietuvos istorija (History of Lithuania), vol. 3 / 13th c. – 1385 / Valstybės iškilimas tarp Rytų ir Vakarų / D. Baronas, A. Dubonis, R. Petrauskas / Baltos lankos [Vilnius, 2011].

Darius Baronas