War Tourism in the 14th Century: What Were European Knights Looking for in Lithuania?

The Teutonic Order was the first Western Christian state that Lithuania came into contact with. The members of the ecclesiastical knights’ order came from the Holy Lands in the 13th century to Prussia and Livonia still not knowing at the beginning that a minor part of their endeavours would gradually turn into the Order’s territorial state. It was only because of their setbacks (in the Holy Land, Hungary, and Cyprus) that forced the knights to focus their energy on the Baltic region. This turning point was symbolized by the moving of the Grand Master’s residence from Venice to Marienburg in Prussia in 1309. The constant wars with the Order for more than one hundred years had a huge impact on the course of Lithuanian history. The Order developed a new tactic for military campaigns called Reisen (the German word Reise is also used in other languages). This is where border settlements were constantly laid waste to with constant attacks and, after a larger number of knights had gathered, they would then plunge into the depths of the land.

An “Agency” for Journeys to Lithuania

It was precisely around that time that the entire swath of land between the Order and Lithuania became a scarcely inhabited territory. The Order was able to implement this new tactic thanks to the fact that crusades to Lithuania became an important cultural element for the nobles of Western Europe in the 14th century.

Lithuania, a periphery land that was little-known, suddenly became an object of interest for Europe’s aristocracy.

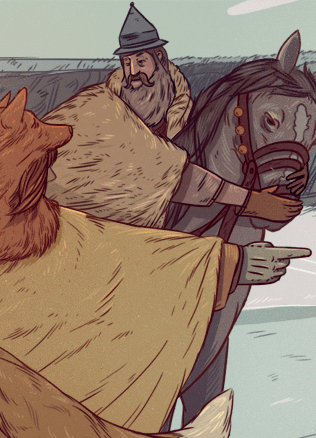

Kings, dukes and other nobles from Portugal to Hungary went to Prussia to take part in holy crusades against the pagan Lithuanians. These wars were important for developing the common culture of European knights, along with developing their style and identity. It was a geographical area where Germans, the French, and the English became members of one class, the miles christianus, or the Christian soldier. For the European nobility, the crusades to Lithuania were not as much for carrying out military goals as a chance to demonstrate knighthood, a kind of tournament for knights in a foreign land. During the crusades, all of the most important rituals of knight culture were carried out, including the dubbing of the knights, the “round tables” of the knights, the tournament jousts. The leaders of the Order were able to create an economy that was adapted for organizing and living off these crusades, included serving the crusade participants, the use of prisoners of war for economic means, and ransoms. Generally, the Order organized two crusades to Lithuania each year (in summer and winter), when the weather conditions were the best. The primary booty of the crusades was people and cattle. Some of the pagans taken into captivity were taken by European knights back to their homeland, as did for example John I, Count of Blois, dressing one Lithuanian up with his heraldic livery. These crusades were commemorated for a long time in Königsberg Cathedral with a display of flags and shields that were left by participants of the crusades, along with other heraldic signs on the walls and stained-glass windows.

The Way of Life of a Knight

The crusades to Prussia and Lithuania became a part of the traditions of certain families, with some families (for example the Warwick family from England) having three successive generations of knights. Often crusade participants went to Prussia several times; among the record holders are the likes of Wilhelm II, Duke of Jülich and his son Wilhelm III who both visited Prussia seven times. There were also those for whom these long journeys became their main way of life. Even though the heralds’ extolling of Rutger Raitz von Frentz from Cologne, who spent 32 winters and 3 summers in Prussia and Livonia seems exaggerated, it reflects the way of life of these people. They would spend their summers in military detachments in the West (at the time the Hundred Years’ War was raging between England and France), and in the winter many knights went to Prussia. European nobles went on crusades with a sizeable entourage: kings and queens were accompanied by a detachment of at least 100 men, counts were accompanied by a group of at least 50 men, and lesser nobles by a group of at least 20 men. The members of more famous dynasties would take their heralds, which would entertain participants with their stories of the knights and immortalize their crusades in stories and images in heraldic books. Among kings, the rulers of Bohemia were particularly active. In the 13th century, famous crusade participant and King of Bohemia Ottokar II (which Königsberg is named after) was replaced by the dynasty of John the Blind in the 14th century, who participated in three holy crusades against the Lithuanians. The last time he participated was in the winter of 1344-1345 together with his son, who later became Charles IV. Data collected by historian Werner Paravicini reveals the impressive number of participants from Western Europe on these Reisen. Thanks to what one could call the “mass tourism of nobles,” the Order organized more than 100 crusades to Lithuanian territory in the second half of the 14th century.

Do You Know?

Lithuania, which became a popular place for war tourism in the 14th century, attracted Westerners with the chance to demonstrate their knighthood, plunder and add to their exotic collections in their manors. The items in demand the most for manor collections were Africans, Arabs and pagan Lithuanians.

The primary gathering point of the knights while making their way to Lithuania was the Grand Master’s residence of Königsberg. It was from there that the Order organized crusades, and gradually expanded their base for crusades to Samogitia and Lithuania. In 1289 they built Ragainė Castle near the River Nemunas, which became an outpost for the Order in their fight against the Lithuanians. They started using ship fleets for longer crusades.

Lithuanians in the Exotic Collections of Manor Estates

In the view of Western European knights, three regions made up the whole of the holy crusades at the time (Spain, the eastern coast of the Mediterranean, and Lithuania). The Earl of Derby Henry Bolingbroke (the future Henry IV of England, the founder of the Lancaster dynasty and main character of Shakespeare’s drama named after him) participated in a crusade to Lithuania in 1390. Perhaps the most famous siege on a castle in Vilnius took place during this expedition, with Vytautas, who had fled to the Order, was in the knights’ army alongside knights from England and elsewhere.

It’s worth noting the weak communication between the West and East of Europe: the future king of England went to bravely fight the “pagans” three years after the Pope had blessed Lithuania’s baptism!

The account book that survived from this crusade reflects the interests of this noble Westerner. Among the various knightly pastimes, there was a clear desire to enrich his collection of “exotic things.” In the West, the pagan Lithuanians are often shown in the collections of what one could call manor house “ornaments” alongside Africans and Arabs. They were kidnapped during the crusades or bought on site. The purchases of the Earl of Derby – two children for one mark – are written among the expenses for wax and nuts. These Lithuanian adventures were not enough for the earl, which is why he left Lithuania for Venice, and from there to fight against the Turks, as they were also enemies. Froissart, a medieval French chronicler, depicted the pagan Lithuanians alongside the Tatars and Persians in the Turkish sultan’s army.

Though Lithuania’s Christianization at the end of the 14th century still did not stop the flow of nobles to it, an economic crisis and internal turmoil overwhelmed the Order, who gradually lost their reason for existing. The Battle of Grunwald became the culmination of this decline. Knights from the West (for example, Burgundian Duke Guillebert de Lannoy) now came to manor estates of Lithuanian rulers to visit and participate in new crusades against new enemies further in the East.

Literature: H. Boockmann, Vokiečių ordinas. Dvylika jo istorijos skyrių, Vilnius, 2003

Rimvydas Petrauskas