When and How Did Jews Settle in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania?

The discussion concerning the settling of Jews in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania is related to the question that has been raised a number of times in the historiography but has never been answered unanimously: what are the origins of the Eastern European Jews? Putting it the other way, the question is why the region, largely underdeveloped in economical terms, proved attractive for most Jews?

Eastern Europe lured Jews with market opportunities and religious tolerance

Jews have a legend that explains the settling of their community in Lithuania (just like in other countries) and substantiates its ancient roots and benefits for the entire society. The legend goes that Jews responded to the letters written by Grand Duke Gediminas (ruled 1316–1341) which he had sent to a number of European cities in 1323 asking merchants and artisans to come to work and live in Lithuania and ensuring them freedom of expression of faith. The legend also specifies the direction of Jewish migration, from Western Europe to Eastern Europe. Modern historians recognize it as one of possible routes noting, however, that it was more characteristic to the turn of the 16th century rather than to the period when Jews began settling in the GDL. Advocates of the theory according to which Jews had moved to the region of the GDL from Western Europe maintain that explicitly worsening attitude of Christians towards Jews in countries of classical Christianity throughout Europe, including hatred-driven assaults and expulsion of Jews from some European countries (England, France and several German lands), was the main reason for their migration. It is likely that the migration has been instigated by broader array of potential activity in the region that lagged behind the West in terms of its economic development. The eastward migration of European Jews remained a dominating trend for a long time, especially after the eviction of Jews from Spain in 1492. Ashkenazi Jews dominated in the region of Eastern Europe. (Ashkenaz was Noah’s grandson; Ashkenazi Jews (Hebrew: ashkenazim) was the term to name the Jews who lived in Germany, northern France and Slavic territories; the term is known since the 14th century).

Jews became part of the GDL together with the lands of Rus’

Although reliable data is very scarce, the arrival of Jews in Lithuania should be linked to Kievan Rus the centre of which, the city of Kiev, would receive Jewish merchants already in the 9th and 10th century, as well as to Poland, the intermediary point of migration from Western Europe.

The GDL has been recognised as a distant point of stoppage for Jews in the east of Europe, the land that bears a positive image as far as the settling of Jews is concerned.

According to the long-standing historiographic tradition, the 1388 privilege by Grand Duke Vytautas to the Jewish community in Brest is considered the first written source that serves as a proof that Jews had settled in Lithuania and had an organised and viable community here. The influences that Jews from Red Russia had to the settling of Jews in the GDL could be perceived both through the reception of the Jewish law and by evaluating political aspirations of the GDL and expansion of state borders in the 14th century. When Gediminas conquered lands of southern Rus, expanded his influence in Rus through dynastic ties and incorporated Volyn into the GDL (in 1340), Jewish communities were already there.

The emergence of first Jewish communities in the territory of the GDL is to a greater extent related to the incorporation of new lands than to Jewish migration in Europe.

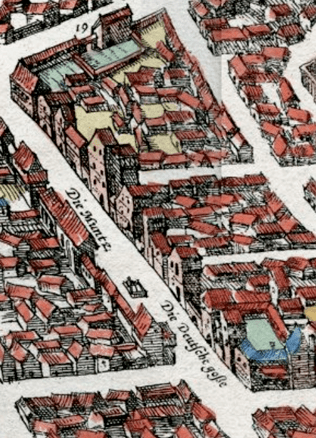

Taking into account the factor of conquests, first Jews apparently arrived in the GDL in the first half of the 14th century. For a long period of time, almost to the beginning of the 18th century, Jews were diffusing mostly in the Byelorussian part of the GDL. Cities in these lands became home for the oldest communities that possessed the resources required for dispersal. Jewish communities are known to have lived in Brest and Grodno in the late 14th century. Karaims settled in Trakai in the late 14th century too. Just a short while later historical sources first refer to Jews in Kiev and Lutsk.

It took a long time for Jewish communities to establish in the Lithuanian territory. The key reason is a cautious position of city dwellers and city owners. The settling of Jews in Lithuania coincided with several important social developments, including late Christianisation and the fact that local cities were undergoing the final stage of their formation. It was then that the first cities were granted Magdeburg rights and merchant craftsmanship started developing in largest urban centres.

Why did Alexander Jagiellon expel Jews from the GDL?

Although Jews have been living in Lithuania since the 14th century, their uninterrupted history starts no earlier than in 1503 when Grand Duke Alexander Jagiellon allowed Jews, whom he expelled from the country in 1495, to return to cities where they used to live. There were virtually no Karaims and Jews in the GDL during the eight years at the turn of the 16th century. A few surviving documents witness that the property of the expelled Jews has been taken over by their relatives or family members who had agreed to convert to Christianity (and thus were able to stay in the GDL). Therefore, one can assume that Jews faced a dilemma of either retaining their faith or turning to Christianity, the move that would allow them stay in cities throughout the GDL they already felt like home. Authorities would forfeit the property of those choosing exile, only to give it over to people loyal to Alexander or to cover huge debts. Alexander’s another possible motive to act the way he did probably was the wish to replicate the decision to expel Jews from Spain by Queen Isabelle I of Castile and King Ferdinand II of Aragon in 1492 (just three years prior to the similar ruling by Alexander), the move that has raised international repercussions and has changed the ranges of Jewish diffusion in Europe. Alexander aimed at creating an all-Christian state by swapping Jews for Catholic Germans, merchants and artisans in the first place. Even though historical sources are too scant to help us understand Alexander’s motives and incentives behind them, the expulsion of Jews from the GDL is a historical fact.

The victorious comeback

Alexander’s decision allowing Jews to come back (“first we banished the Jews from our state, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, but now we let them enter our state again”) and its conditions were set in his 1503 privilege, the first document in the GDL that covered all the local Jews and served as a legal basis for the revival of the Jewish community in the GDL. Not only has the aforementioned privilege issued by Vytautas to Jews living in Brest drawn a considerable attention of researchers, but it has also overshadowed the importance of the Alexander’s privilege in the historiography, even despite the fact that the latter is the earliest document intended to all Jews living in the country and the first legal act that legalises the settling of Jews in the GDL. Alexander restored their ownership of immovable property (an exceptional decision in Europe), left its taxation unchanged and ensured Jews could do business as traders. He also decreed that all debts of local residents against Jews were still valid. Part of the banished Jews moved back to the GDL, but the Jewish community was growing bigger due to the influx of people from Western and Eastern Europe too.

Jurgita Šiaučiūnaitė-Verbickienė