When Forging Royal Documents, Avoid Green Wax

At the end of 1512, Abraham Józefowicz, the royal treasurer, brought one Pancras, citizen of Smolensk all bound in chains, to the Lower Castle to the court of Voivode of Vilnius Mikołaj Radziwiłł. Pancras had already confessed to the treasurer about trying to use a forged document and was now expected to confirm this in court.

“The document was written in Your Grace’s chancellery by Your Grace’s scribe Jonaitis,” said Pancras in a low and hoarse voice.

He knew very well that he faces a severe punishment of death by burning.

Aimed at illegal trade in silver

This story began more than six months ago. In the spring of 1511, Sigismund the Old, the king of Poland and the grand duke of Lithuania, and his royal cohort arrived in Brest (present-day Belarus). Then Pancras reached Brest too. He had come to an agreement with the scribe at the service of voivode of Vilnius, named Jonaitis, that he would forge a document. Not just any document, but one complete with the royal signature and seal, granting Pancras the privilege of trade in silver with Muscovy, although such dealing went against the Lithuanian law.

“

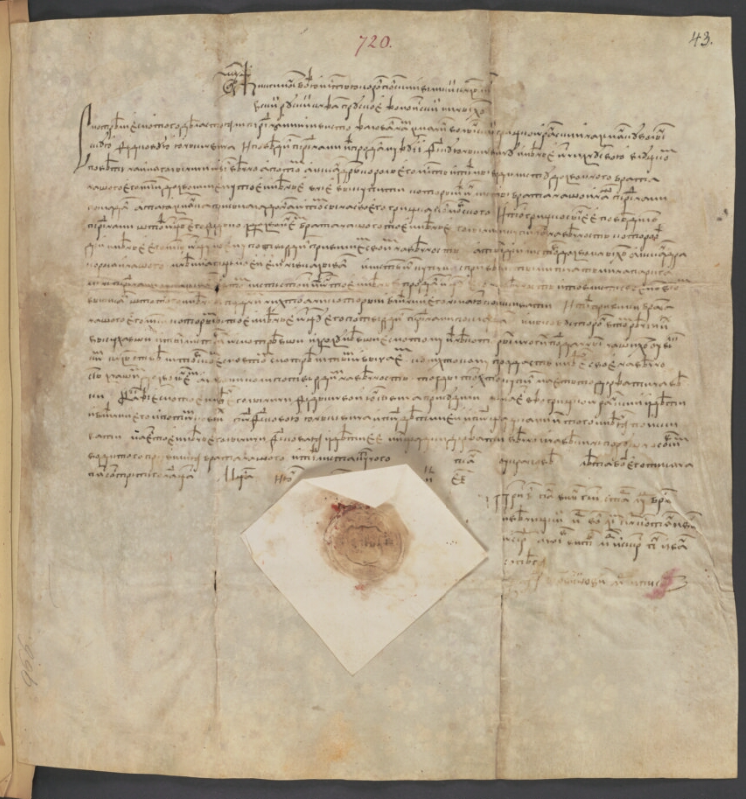

We do not know the exact contents of the document, yet we may assume beyond reasonable doubt that it looked very much alike to a genuine document issued by the royal chancellery.

We do not know the exact contents of the document, yet we may assume beyond reasonable doubt that it looked very much alike to a genuine document issued by the royal chancellery. Jonaitis even broke off an original seal from another document kept his master’s archive and attached it to the forgery.

Therefore, Pancras could have felt confident. On the one hand, it was unlikely that the forgery would be ever found out. On the other hand, hardly anyone could notice his meetings with Jonaitis, as Brest was teeming with strangers: royal courtiers, Lithuanian magnates and dukes accompanied by their cohorts.

In a fake document, every tiny detail counts

At the end of 1511, perhaps due to a sheer coincidence, Pancras’ wares were detained by customs and the suspicious document bearing a royal seal was given to the Voivode of Smolensk Jerzy Hlebowicz. Ostensibly, it was all because of the wax of the royal seal. Under the paper security layer attached to the seal, the custom officers found two kinds of wax: red and green. The royal chancellery used red wax exclusively.

“

Ostensibly, it was all because of the wax of the royal seal. Under the paper security layer attached to the seal, the custom officers found two kinds of wax: red and green. The royal chancellery used red wax exclusively.

Ostensibly, it was all because of the wax of the royal seal. Under the paper security layer attached to the seal, the custom officers found two kinds of wax: red and green. The royal chancellery used red wax exclusively.

Before long, a royal scribe named Bogukhval arrived in Smolensk. He said the monarch had never asked to write the document in question and confirmed that the safety paper attached with green wax to the fake was originally removed from another document.

Pressed by immediate danger, before the forgery was found out, Pancras ran to Vilnius. Although we know little about his plans, such decision seems logical. He was well known in Smolensk and its roundabouts.

Do You Know?

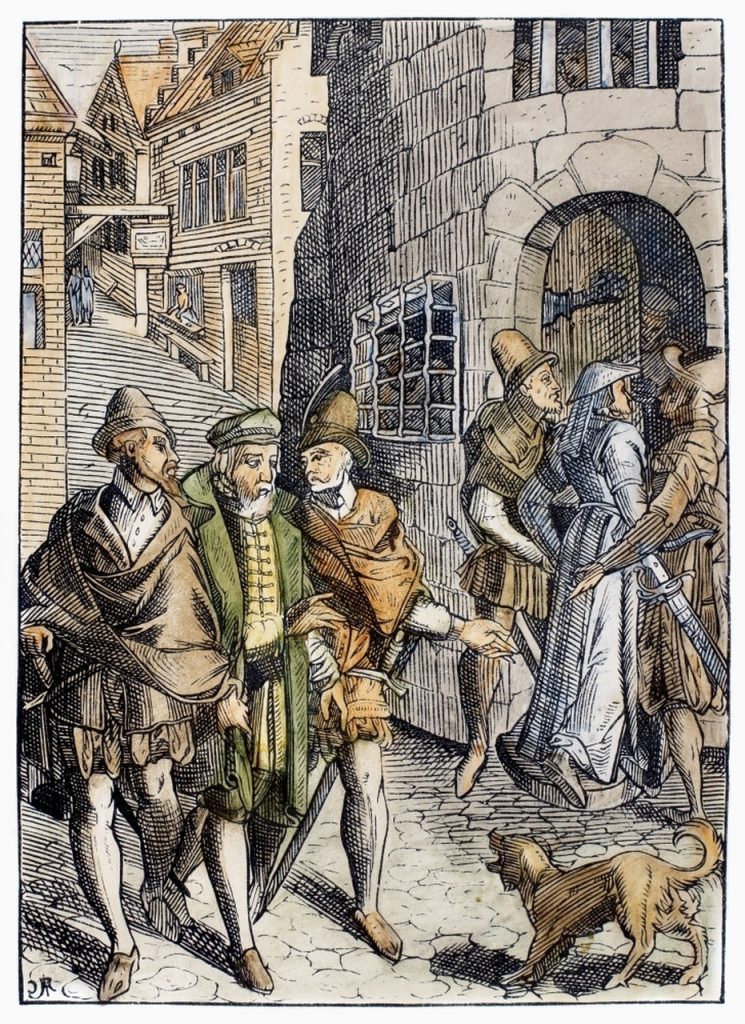

Vilnius was one of the largest cities in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. Anyone wishing to hide or stay incognito could easily do so there. Many court hearing records attest that dozens upon dozens of offenders found shelter in Vilnius.

Moreover, the city was hosting a Sejm in the beginning of 1512, therefore the Council of the Lords gathered there with all their relatives, helpers, and servants, filling Vilnius with many outsiders.

The offender detained by a treasurer

The Voivode of Smolensk had no clue about Pancras’ whereabouts, therefore he sent out letters to many officials, asking to detain the offender. Abraham Józefowicz, the royal treasurer, who arrived to Sejm in Vilnius alongside hundreds of others, had read the letter. By a lucky coincidence, he met Pancras earlier and once he saw him in one of the city streets Józefowicz detained him in the cellar of his house.

Later he described the matter in a letter to his friend royal scribe Jan Sapieha.

“

In and around the 16th century, the legal system of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania allowed for imprisonment or release of suspects on bail prior to the legal proceedings.

“I was going home from the Vilnius castle, where the meeting of Their Graces Council of the Lords had taken place, and I spotted that poor Pancras, walking down the street and hiding his identity from those near him. I immediately ordered his arrest and held him chained for about two weeks in my cellar. Then I brought him to court of Voivode of Vilnius.”

In and around the 16th century, the legal system of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania allowed for imprisonment or release of suspects on bail prior to the legal proceedings. Bail was the more honourable alternative mostly applied toward individuals of higher rank. They were then compelled to suspend their official duties until the end of the trial. While an imprisoned person almost inevitably lost external signs of nobility and higher social rank.

Castle towers, cellars in the Town Hall, and sometimes in private homes served as temporary prisons in Vilnius. In this respect, the 16th century Vilnius was very similar to other cities in Central and Eastern Europe. The underground premises were damp, dark, and cold. The suspects spent there anything between several days and one year, many passing away before the trial had even begun. Only the most resilient would eventually meet their judge and, possibly, the executioner.

Andrej Ryčkov