A Place Behind the Counter as a Way to Socialise

Trade is an indispensable attribute of any city and the capital of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, Vilnius was no exception. Until the end of the 16th century, it remained one of the most important Eastern European centres for transit trade, while Vilnius-based merchants ranked among the city’s most influential residents. In addition to that, the trading network involved all kinds of artisans, resellers, and a multitude of shopkeepers. The latter category included a considerable number of women. The fact seems perfectly customary nowadays, but several centuries ago trade was one of very few jobs that women could undertake to feel as valuable members of the society.

Four categories of female traders

It has to be said that men oversaw all major trading operations. That was the rule without a single exception. The role of women – where, what, and how much they were selling – heavily depended on their individual social status.

All female traders of Vilnius fall into four groups:

- Very few wives or widows of wealthy merchants and artisans;

- Several dozen women who leased small shops;

- Several dozen women who had stalls in the Town Hall Square or other markets;

- More than fifty other small street vendors.

“

In Vilnius, women ran important trading transactions only as temporary successors of their late husbands. Even then their job was usually limited to settling earlier deals.

No archival document suggests that a woman in Vilnius ever managed transnational trade operations. In neighbouring Poland, as historian Maria Bogucka attests, at least several females are known to have been in charge of large-scale imports and exports, a risky business that required physical energy, psychological resilience, and a set of special skills, such as book-keeping and foreign languages.

In Vilnius, women ran important trading transactions only as temporary successors of their late husbands. Even then their job was usually limited to settling earlier deals. In the late 17th-century Katarzyna Walentinowicz paid the servants of her late husband Simon Narbutowicz in salt for transporting the wine from Vilnius to Königsberg.

Small fry

“

In the late 17th century, Ana Fombegena worked as a jeweller for six years, while the 18th-century documents list Konstancja Honorska and two other female guild members.

Vilnius merchants’ wives sometimes worked behind the counter in family stores. In 1666, the wife of Jan Kukowicz, a merchant and burgomaster, inherited his shop and 2,000 zlotys worth of goods, mostly salt. In the early 18th century, merchant Friedrich Liedert’s wife Catherina Zahorska worked in her own grocery store. However, such examples were very few in the Old Vilnius.

The same is true speaking of Vilnius artisans, although most of the city’s guilds allowed widows to continue with the trade of their late husbands, sell their production, and even hold high offices in the guild, at least until her next marriage. History of the city’s oldest guild uniting goldsmiths offers several examples. In the late 17th century, Ana Fombegena worked as a jeweller for six years, while the 18th-century documents list Konstancja Honorska and two other female guild members. They either sold their production themselves or employed help.

Women thrived in small trade

Small scale trading was the one sector where women truly dominated. The 1662 tax papers from the magistrate show that at least 53 women paid annual fees for either owning or leasing shops and open-air stalls on the Town Hall Square alone.

Many more women traded in other markets around the city or just in the city streets. The income and expenditure books of Vilnius from 17‒18th centuries retain the taxes levied from traders living in Vilnius.

Do You Know?

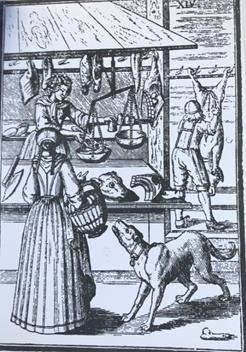

The Town Hall Square was the main trading area where sellers, including dozens of women, daily displayed barrels of pickled cabbage, bottles of oil, boxes of raw and smoked fish, rolls of cloth, several types of bread, cakes, fresh vegetables, cheese, chicks, geese, and other poultry.

In 1731, women paid tax for 68 pastry shops. In addition to that, at least 25 female sellers specialised in groats, twenty traded eggs, and another eleven sold cheese.

An arduous and risky job

“

The Town Hall Square was the city’s main trading area three or four centuries ago. Back then it accommodated two parallel rows of small stores and a number of warehouses. Out for shopping, residents of Vilnius would also visit adjacent streets, such as Didžioji, Vokiečių, and Stiklių, where merchants and artisans had dozens of stores too.

Female traders could be as young as their teens and up to well over fifties. Often even very young girls ventured out on the street to earn some money by selling flowers and other goods. Their job was far from safe and children had to be on the lookout against all kinds of evil. A municipal court book features a 1560 record about Margarita, a nine-year-old girl, who was selling lettuce beside the Church of the Holy Spirit when a client, some Stanisław, asked her to take his purchase home only to trap and rape her in his house.

The number of small shops in Vilnius fluctuated and heavily depended on political developments. In 1647, the magistrate collected fees from as many as 720 retail outlets, including almost 400 food stores and more than 130 artisan shops. Fifteen years on, in 1662, after the plague pandemic had swept the city, the number of shops fell to just 341. In the midst of the Northern War and after a yet another outburst of plague, in 1713, just 168 shops remained open. But in 1749, after the wounds had healed, their number topped 900.

The Town Hall Square was the city’s main trading area three or four centuries ago. Back then it accommodated two parallel rows of small stores and a number of warehouses. Out for shopping, residents of Vilnius would also visit adjacent streets, such as Didžioji, Vokiečių, and Stiklių, where merchants and artisans had dozens of stores too.

From bread to exotics

At best of times the city centre boasted at least three dozen shops that specialised in either eggs or pastry. Groceries and haberdashery were popular too. These shops mostly employed women and usually offered a wide variety of commodities, from spices to metal produce. For example, in 1725 Katarzyna Packiewiczowa’s grocery shop offered pepper, Venetian caraway, clove, laurel leaves, cinnamon, rosemary, wormwood roots, dried orange rind, candles, glasses, paper, glassware as well as sulphur, alum and blue vitriol, the latter three used for tanning leather. In 1744, Mariana Szydlowska’s store sold ice sugar, anis, mustard, ginger, rice, playing cards, pins and knives.

“

Merchant Simon Narbutowicz’s wife Katarzyna apparently was known for a selection of unconventional wares in her grocery shop in Vilnius. According to a 1676 inventory, she sold pistols, cartridge bags, bows, swords, knives, scissors, saddles, stirrups, reins, bits, but also nails, scythes, frying pans, cloth, and skins.

Merchant Simon Narbutowicz’s wife Katarzyna apparently was known for a selection of unconventional wares in her grocery shop in Vilnius. According to a 1676 inventory, she sold pistols, cartridge bags, bows, swords, knives, scissors, saddles, stirrups, reins, bits, but also nails, scythes, frying pans, cloth, and skins.

Best shops were owned by the members of the magistrate, the wealthiest merchants, and master guildmembers. Ordinary traders often operated in tiny, cramped premises, sometimes located in cellars. Their interiors were usually quite simple, consisting of a table, a cupboard or a coffer, and several shelves. Shop displays were extremely rare even in the 18th century and promoted gloves, jewellery, and haberdashery.

Variety of scales and weights were used to determine the weight of the goods, counting was made easier by certain special marble boards.

By Raimonda Ragauskienė