Dancing and Firework Displays: The Essentials of a Banquet in Old Vilnius

Wealthy residents of Vilnius have always loved to party but penchant to celebrate in large numbers gained popularity only in the 17-18th centuries. At that time the municipal elite and the magnates residing in Vilnius organized balls that attracted all the prominent people of the capital.

“

Just about any occasion could be taken as a pretext for a ball, including birthdays, personal name days, weddings, the start of dietine and Lithuanian Tribunal sessions, as well as royal coronations and royal name days. Large companies of friends and relatives gathered during Christmas, Easter, and Mardi Gras.

Just about any occasion could be taken as a pretext for a ball, including birthdays, personal name days, weddings, the start of dietine and Lithuanian Tribunal sessions, as well as royal coronations and royal name days. Large companies of friends and relatives gathered during Christmas, Easter, and Mardi Gras.

Judging by the 1632 diary of Chancellor of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania Albrycht Stanisław Radziwiłł, he was used to partying at least three to four times a month.

Aristocrats mostly organised festivities in their private palaces, while the Town Hall usually hosted the public celebrations. On rare occasions municipal officials would safeguard the municipal treasury and refuse to fund such events, but their peers would always find ways to persuade them. In April 1667, members of the Vilnius City Council detained Piotr Korona, the municipal treasurer, and held him prisoner until he agreed to allocate money for the entertainment of the wojt and the council members.

The art of hosting a party

Every big celebration required scrupulous preparation. In the 17th century, the Baroque culture demanded utmost ingenuity from hosts, most of whom wanted to stun their guests. A number of relevant textbooks have been written. One of them, published in 1660 in Kraków, instructs the hosts to be smart and merciful, but not stingy. The premises, it continues, must be cleaned thoroughly, flies and fleas chased away, water and white cloths must be provided to clean the dishes. And get all the dogs with their hairy tails out, the book says. Another author taught the hosts to avoid saving on small things: “It is better to suffer a loss worth a thaler than a disgrace for the saved penny.”

Several hundred ladies and gentlemen attended large balls. The hosts, smiling and ornate, would welcome them at the main entrance of their glowing home. Count Stanisław Tyszkiewicz decorated the entrance to his palace in May 1773 with a “splendid and grandiose symmetry of fire”. Closer to the building, the guests were surrounded by intricate illumination.

Weddings and other major parties usually lasted for several days and up to a week. On less momentous occasions, the gatherings would normally begin in the late afternoon and end by late night or sunrise at the latest.

Were we to believe the documents of the municipal court, some parties were held only to distract. In January 1710 Burgomaster Maciej Kazimierz Gudielewicz sued a middle-ranking municipal official Hrehory Stefanowicz Wargałowski, charging him with home invasion. Apparently, Wargałowski asked his wife to arrange a party that “included music, dancing, drinking and shouting vivat” and surrounded by several friends proceeded to plunder the burgomaster’s house.

Guests always want to dance

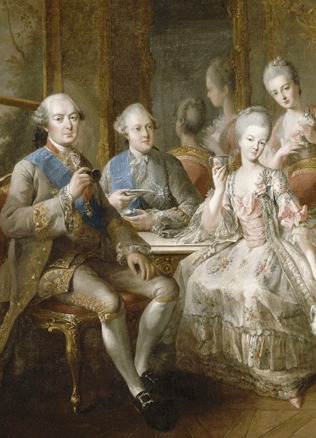

An aristocratic celebration was unimaginable without music, dancing and fireworks. One expert on party etiquette wrote that the only way to enjoy a party was to do it calmly; the music should not be too loud, the dances not overly emotional, and the best thing being a quiet stroll in a park. Such provisions, however, were by no means popular. In the 18th-century Vilnius, polonaise and mazurka were the two most popular dances, but noble guests also danced minuets, counter-dances, and allemandes.

“

Few followed another suggestion the etiquette expert made, that of abstaining from gambling. Dozens of men and women played cards and dice, often for money.

Few followed another suggestion the etiquette expert made, that of abstaining from gambling. Dozens of men and women played cards and dice, often for money.

One ball in Vilnius in January 1773 started with guests dancing, servants offering them a variety of drinks. In the middle of the hall stood a table laden with food. Afterwards, the guests watched a sumptuous firework display through the windows. Later they went to the colourfully illuminated main gate. Finally, about 200 people took their seats at two huge tables and the dinner began.

Fighting for the best seats

“

Overall, parties were laden with a multitude of unwritten rules. Everyone knew who deserved to be offered a chair, when and before whom the door should be opened, when it was necessary to take the hat off, when giving a hand was appropriate, and when a simple nod was enough.

Hosts had to ensure the proper seating of the guests. Despite that, many parties witnessed bickering among officials who were ready for anything to get a seat as close to the king as possible. Some saw nothing wrong in pushing women away from their seats. During the rule of Jan Sobieski such hot heads were not allowed to sit at the ruler’s table. To avoid misunderstanding, hosts used round tables or provided no seating at all. Some magnates hired a person to read the guestlist and show each guest their seat at the table.

Overall, parties were laden with a multitude of unwritten rules. Everyone knew who deserved to be offered a chair, when and before whom the door should be opened, when it was necessary to take the hat off, when giving a hand was appropriate, and when a simple nod was enough.

According to food historians, the French model of serving food was the most popular one in 17-18th century Europe: the servants brought all dishes to the table at once. In all likelihood, the same manner was prevalent in Vilnius. Only in the 19h century this way of serving was substituted with bringing out dishes one after another.

Products and dishes

According to multiple sources, mixing contrasting tastes such as sweet and sour was popular up to the 17th century. Chefs across the Grand Duchy of Lithuania used a lot of spices, their overall style reminiscent of German cuisine. Italian and Oriental influences became noticeable in the 16th century.

Do You Know?

Large sways of Europe went through a “culinary revolution” in the 17th century, when the French cuisine became dominant. People started consuming less meat, especially stuffed and heavily seasoned meats that were popular throughout the Middle Ages. Plain meat was gradually replaced with meat and vegetable stews. Sugar, considered a stand-alone dish in the Middle Ages and used in meat cooking, was now becoming an attribute of confectionery. The motto of the “new wave”, just like nowadays, was naturalness and freshness.

In the GDL, though, meat dominated the local cuisine until the late 18th century and the influence of French cuisine remained relatively limited. The nobles mostly preferred beef, veal, and poultry, one example being Stanisław Radziwiłł, whose 15 January 1783 home menu includes a soup with dumplings, fried lamb, hazel grouse with red cabbage, fried chicken with champignon sauce, and fried rooster – and that’s for lunch only. His dinner consisted of broth, pears, soft-boiled eggs, and chicken.

Often did party hosts treat their guests with bigos, a Polish stew of chopped cabbage and meat. Inspecting copious tables of such banquets, a modern person would probably be surprised by the vessels full of caviar, a cheap product several centuries ago.

Jerusalem on the table

Party hosts usually wanted to astound their guests with the abundance of food, as well as its shapes and colours.

According to 17th-century accounts, Grand Hetman of Lithuania Paweł Jan Sapieha once served food in a remarkable manner. First, the servants brought in four large roasted boars symbolizing the four seasons. Then, twelve roasted deers (months) appeared followed by 365 sweet cakes (days). Later, 52 silver barrels of wine (weeks) were opened to the guests and 8,700 quarts of mead (the number of hours in a year) were given out to the servants.

Voivode of Vilnius Mikołaj Krzysztof Radziwiłł’s servants brought out three giant pâtés and upon seeing them, the duke exclaimed: “Gentlemen, to arms!”. When the cap covering the first pâté was lifted, a flock of live partridges and other birds rose to the ceiling. Moreover, Radziwiłł’s chefs had built bread hills, almond palaces, and fortifications. According to one witness, this was a “Jerusalem-like landscape” was there complete with sugar crusaders, red crosses on their cloaks, guarding the walls.

A pâté, it has to be said, was among the highest culinary achievements. A pâté chef was an extremely respectable trade. Made of meat, vegetables, fish and cheese, pâtés were consumed both cold and hot, as a main course and as a snack.

By Aivas Ragauskas