Executioners in Vilnius: Trade and Life

Vilnius, just like other cities of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, employed executioners since the late 15th century. Before then, their grim job was carried out by other people, such as exonerated criminals. Podlachia, the region in today’s Poland, was the first among the lands of the GDL to employ full-time executioners because there self-rule developed the earliest. King Casimir’s penal code of 1465 warrants torture in cases regarding stealing. The three Lithuanian Statutes (1529, 1566 and 1588) also mention executioners. The Third Statute (1588) instructs the castle courts across the GDL to employ executioners, yet it is unclear just how diligently the order was followed.

First executioners in the old Vilnius

“

According to the Magdeburg privilege of 1432, the wójt (mayor) of Vilnius had the right to administer capital punishment, the practice that calls for the existence of an executioner. The first documented action of Vilnius’ executioner, however, is much later: in 1580 he beheaded the magnate turned traitor Grzegorz Ościk in the Town Hall Square.

We do not and probably will never know when the first executioner began working in Vilnius. The turn of the 15th century is the most likely period, because the time when the city’s right to self-rule was introduced. According to the Magdeburg privilege of 1432, the wójt (mayor) of Vilnius had the right to administer capital punishment, the practice that calls for the existence of an executioner. The first documented action of Vilnius’ executioner, however, is much later: in 1580 he beheaded the magnate turned traitor Grzegorz Ościk in the Town Hall Square.

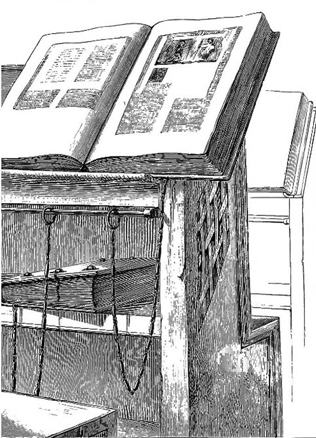

It was in the same square that the executioner burned dozens of books deemed heretical on 14 April, 1581, just before Easter. Teodor Narbutt, who lived two hundred years later and left the most detailed account of the event, might not be the most reliable source, yet he says that on that day, early in the morning, several carts carrying firewood, bunches of straws, and books, arrived to the square. The executioner, assisted by Dominican monks, dumped the firewood and straws into a pit before topping it with the books. Then a priest gave a speech and, after a Dominican exorcist handed him the torch, the executioner Ignacy performed certain ceremonies and set the books ablaze. Thick clouds of smoke kept rising to the skies for the remainder of the day.

Ignacy, Andrzej, and their colleagues

“

Mesterhazi might have been the last full-time executioner in Vilnius. Most likely a German, he appears on many occasions in the books of municipal expenses for the year 1797. Mesterhazi died at the end of 1797 and the magistracy of Vilnius paid for his funeral and, ostensibly, employed no other executioner after him.

If the abovementioned information is truthful, it gives us the name of the first documented executioner in Vilnius – Ignacy. Historical sources also mention other executioners who worked in Vilnius in the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries. They are Andrzej Wroblewski (1657–1671), Johann Rosovien (1675–1677), Paul Lipknecht (1677–1678), Adam Estermann (1679–1692), Nicholaus (1693–1712), Friedrich (1712–1737), Martin (1750?–1752), Schmidt (1752–?), and Mesterhazi (?–1797).

Mesterhazi might have been the last full-time executioner in Vilnius. Most likely a German, he appears on many occasions in the books of municipal expenses for the year 1797. Mesterhazi died at the end of 1797 and the magistracy of Vilnius paid for his funeral and, ostensibly, employed no other executioner after him.

Mesterhazi himself was apparently too frail to work during his last years, therefore Vilnius hired an executioner from Grodno to perform his duties for him from 14 January to 5 February in 1797 and from 19 April to 6 May that same year.

None of the known executioners were local. Usually, Germans from Königsberg or Poles from Kraków filled this position. Most of them lived in Subocz gate.

The costly affair of hiring an executioner

“

The executioner was a municipal officer, one of his important functions being torture of suspects in important cases under supervision of court officials. The torture, aimed at getting a confession, was forbidden against public officials, pregnant women, and children younger than 14.

Smaller cities of the GDL often could not afford having a full-time executioner, therefore they often hired one from the larger cities like Vilnius. At times the capital also borrowed them from elsewhere, including Lida (in 1678 and 1679), Kaunas (1679 and 1692), Kėdainiai (1693), and Königsberg (1737).

The executioner was a municipal officer, one of his important functions being torture of suspects in important cases under supervision of court officials. The torture, aimed at getting a confession, was forbidden against public officials, pregnant women, and children younger than 14.

Understandably, the executioner was in charge of carrying out court sentences, from the mildest ones (like expelling from the city) to capital punishments by hanging, beheading, quartering, burning, drowning, burying alive etc. For each one, the executioner received a fixed payment decided upon by the municipal government. The executioner was also required to remove faeces and dead animals from the streets and out of the city, catch stray dogs, and supervise the city prison. To carry out most of these tasks, however, he would hire assistants.

Heaps of gold and public disdain

In the mid-18th century Vilnius, an executioner earned 300 złotys a year, a huge amount that topped the salary of a burgomaster (250 złotys) and was thrice as high as than that of a municipal assessor, who was paid 100 złotys a year. Executioners received additional money for torture, executions, disposal of dead animals and other work. Just as any other servants of the city, they received presents from the city on the occasion of the most important Christian holidays. They were given red cloth for clothing, as the executioner of Vilnius was obliged to wear red, following the German fashion. He also received cereal for sustenance.

Very few envied his position though. Executioners were essentially social outcasts, albeit in the 16th century some lawyers started arguing that the trade of an executioner bears virtue because it is important for the society.

Do You Know?

The executioners lived within a specific subculture, married each other’s daughters and widows. Ostracised by the wider society, they were often addicted to alcohol and spent their free time in brothels. Detested by the majority of citizens, they would sometimes suffer violence, like Johann Rosovien, a German who worked in Vilnius between 1675 and 1677 and was shot dead by an unknown man.

Torture without Wester-style

“

The men and women were tortured for grave offenses, primarily related to faith.

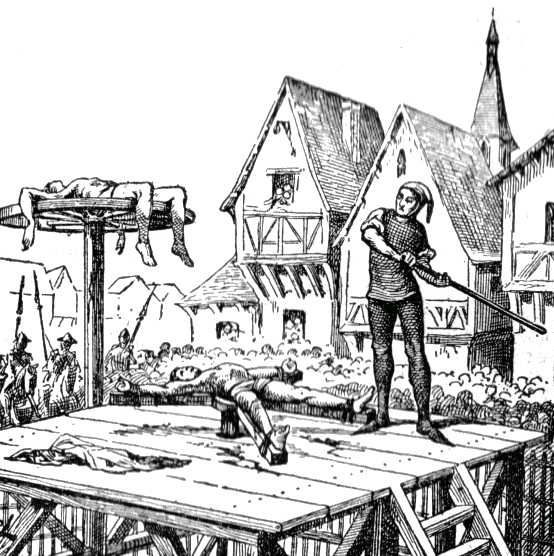

In Lithuania, not unlike the rest of Europe, offenders would undergo cruel torture before death, which included whipping, use of red-hot pincers, and ear cutting. The men and women were tortured for grave offenses, primarily related to faith. Whipping at the post, known as post of disgrace, was among the lightest punishments administered for a first-time petty theft. The whipping post was decorated with the head of Themis, the goddess of justice. This is why those tied to the post were said to be “kissing the hag of the Town Hall.”

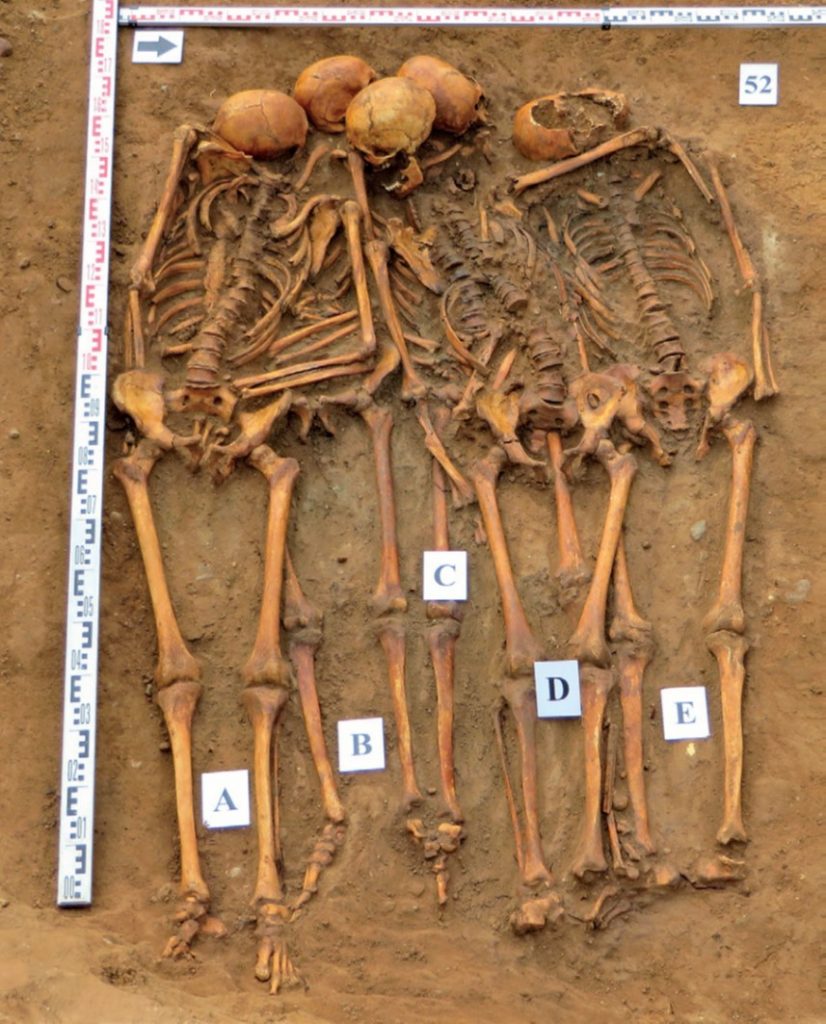

Wheeling was perhaps the most brutal punishment, which called for breaking bones before installing the disfigured body into a wheel on a high pole so that all the citizens could see the dead criminal. Other harsh sentences included impaling, quartering, and burning. The execution was usually preceded by three rounds of torture.

The executioners in Vilnius, compared to their counterparts in Western Europe, where the art of torture was elaborate, used relatively simple tools, such as iron hooks, pincers, ropes, knives, candles etc.

The executioner’s sword

“

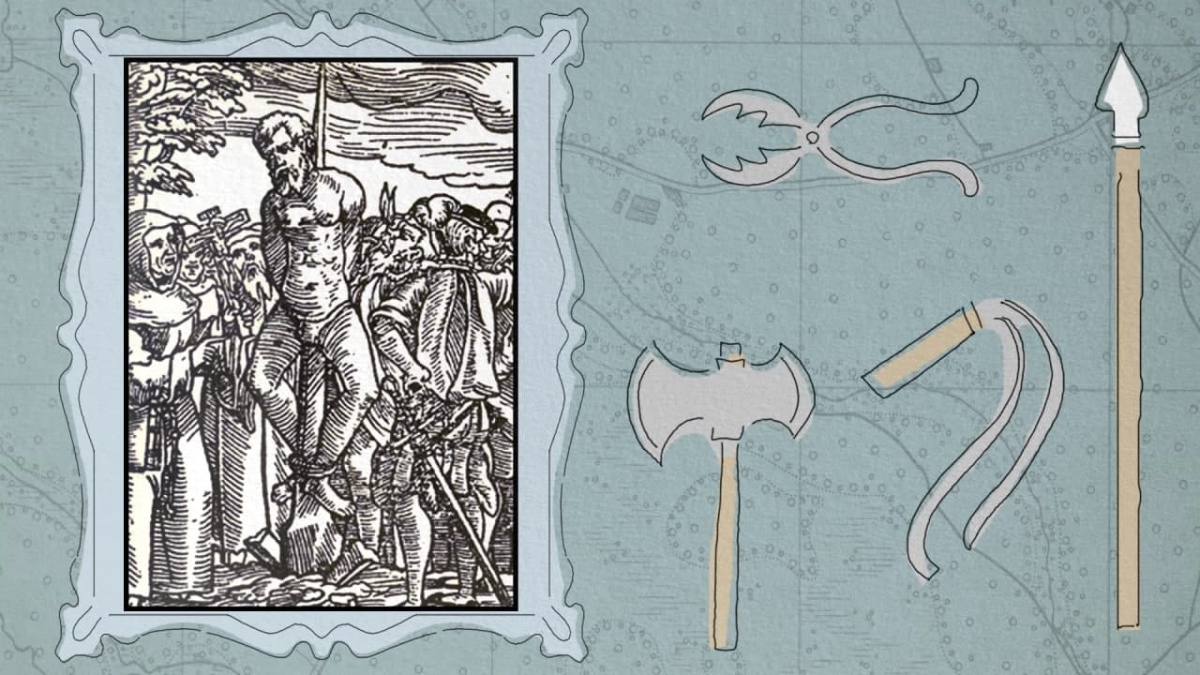

The main weapons used to carry out capital punishment were a sword and double-edged axe.

The main weapons used to carry out capital punishment were a sword and double-edged axe. The original sword, featuring a wooden handle with a copper finish, an image of Themis, and an inscription in German, was lost in the early 20th century.

Another double-edge sword, found in 1928 in Vilnius, bore two writings in German: “Whenever I raise this sword, I wish the villain life eternal” and “When I destine a sinner to die, he falls into my hands.” The sword was last seen in a Belarusian museum during the interwar period.

Aivas Ragauskas