Franciscans, the First Archaeologists in Vilnius

In the first half of the 17th century, Western and Central Europe was devastated by the Thirty Years’ War (1618–1648), the last of the brutal religious wars between Protestants and Catholics.

Meanwhile, for the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth these were its golden years. The nobles relished in the perfection of their parliamentary system and enjoyed the atmosphere of surprising religious tolerance. Even in economic terms, this was a time when not only the rich were getting richer.

However, the idyll did not last. In 1648, the same year the Peace of Westphalia was signed, the situation changed, as the Cossack uprising broke out on Ukrainian plains. Several catastrophic defeats of the Polish army later, a huge state spanning from Silesia to Smolensk found itself at the edge of the abyss of chaos and political paralysis.

A hunt for relics amidst political turmoil

As the dramatic events were unfolding in faraway Ukraine, Vilnan Franciscan monks set out for a peaceful mission of archaeological investigation. They aimed to find the remains of the 14th century Franciscan missionaries martyred at the hands of pagan Grand Dukes Gediminas and Algirdas. Bearing this goal in mind, Franciscan vicar Stanisław Neoforan approached the Vilnius cathedral chapter on the cold morning of 17 December 1649.

“

Franciscans aimed to have the relics unearthed by Tyszkiewicz’s ingress into the seat of Vilnius Bishop. In January 1650 he suggested the monks waited until the next spring, however, work did not start that year. Perhaps, the Franciscans wanted to be better prepared for the excavation.

Upon hearing his request, the prelates and cannons of the chapter sent a letter of recommendation to the appointed Bishop of Vilnius Jerzy Tyszkiewicz (1649–1656). He backed the Franciscan initiative to canonize the martyrs, claiming that “the patrons of our Duchy” deserve the glory of the altars.

Franciscans aimed to have the relics unearthed by Tyszkiewicz’s ingress into the seat of Vilnius Bishop. In January 1650 he suggested the monks waited until the next spring, however, work did not start that year. Perhaps, the Franciscans wanted to be better prepared for the excavation.

In the autumn of 1650 a special commission was set up and charged with finding the precise location of their interment. However, its efforts proved fruitless. Therefore, in the spring of 1651, a group of Franciscans, spades in their hands, walked to the monastery of the Order of the Hospitallers of Saint John of God, in the vicinity of the present-day Presidential Palace.

Bohemian Franciscans in Vilnius

According to reliable historical sources, during the last years of Duke Gediminas’ reign (he died in 1341), the routine in Vilnius, then a fairly small town, was somewhat interrupted by the arrival of two Bohemian Franciscans: Ulrich of and Martin.

“

The enraged heathens seized him and took him to the Livonian [!] duke Gediminas. The monk firmly confessed his Catholic faith and decried their abhorrent pagan rites, the furious duke ordered he was cruelly murdered and his body parts scattered. Moreover, upon learning he had a friend, Gediminas sent his servants to bring brother Martin over.

“Burning with the flame of faith and martyrdom they arrived to the aforementioned castle of Vilnius, inhabited by the worst heathens worshiping abominable things,” the Chronicle of 24 Generals says. “One day, when the aforementioned brother Martin was celebrating mass at the Franciscan abode, the aforementioned brother Ulrich, banner of the cross high in his hand, stepped out on the street and preached fervently to the heathen crowd, urging them to worship the true living God, abandon superstition and fake gods.” The enraged heathens seized him and took him to the Livonian [!] duke Gediminas. The monk firmly confessed his Catholic faith and decried their abhorrent pagan rites, the furious duke ordered he was cruelly murdered and his body parts scattered. Moreover, upon learning he had a friend, Gediminas sent his servants to bring brother Martin over. Grand Duke Gediminas asked him: why did he arrive in this city? Once Martin answered he came to reveal the fault of the duke and his people and to call them to worship the only true God, the duke immediately ordered he be thrown in prison.”

Do You Know?

Soon the Franciscan monks heard their harsh sentences. Most likely, Ulrich was buried in some unidentified church somewhere beside the riverbed of Nemunas in what was then Prussia – that’s how far downstream his corpse travelled. While Martin’s remains were buried in the Orthodox convent where Gediminas’s sister lived.

The slaughter of Vilnan Franciscans

“

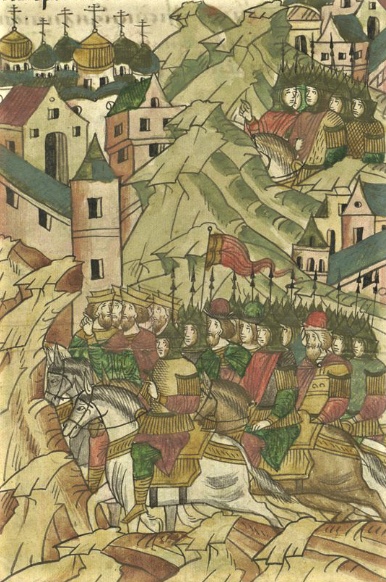

According to the legend included in the Bychowiec Chronicle, once Grand Duke Algirdas marched out against Muscovy “pagan residents of Vilnius assembled a large crowd and went to the monastery. Unwilling to accept the presence of Roman Christians, they burned down the convent and chopped seven monks into pieces, while the other seven monks were tied to wooden crosses and sent downstream Neris, and they said, ‘You came from where the sun sets, now return to where the sun sets. Why did you annihilate our gods?’”

It is worth noticing that visitors were much eager to proselytize than their brothers permanently residing in Vilnius, who were used to a quieter life and avoided annoying the heathens and their potentates. However, some boundaries were crossed in 1369, when all inhabitants of the Vilnius Franciscan monastery, the four brothers and their guardian, were murdered. Why, where, and how it happened remains unclear.

Contemporary 14th-century sources provide very few hints. The dead guardian, apparently, repeated brother Ulrich’s postmortem trip to Christian Prussia. Reliable historical records do not name the burial place of the remaining Franciscans, but the 16th century saw the birth of at least several legends related to the events. It was these legends that the 17th-century Franciscans used as their primary sources in the search for their murdered brothers.

According to the legend included in the Bychowiec Chronicle, once Grand Duke Algirdas marched out against Muscovy “pagan residents of Vilnius assembled a large crowd and went to the monastery. Unwilling to accept the presence of Roman Christians, they burned down the convent and chopped seven monks into pieces, while the other seven monks were tied to wooden crosses and sent downstream Neris, and they said, ‘You came from where the sun sets, now return to where the sun sets. Why did you annihilate our gods?’”

Much later, people started to believe that the first seven Franciscans were killed in the Town Hall Square, while the other seven were nailed to crosses on the Bald Hill and thrown into Vilnia river. This hill is now known for the Three Crosses monument, restored in 1989.

Search area defined by legends

“

By the time Franciscans decided to find the remains of their ancestors, a number of new buildings had been erected on and around the site, changing it considerably. Moreover, the land was now owned by the Hospitallers who did not share the interest in Franciscan relics.

Old legends dating back to the 16th century spoke of the bishop’s garden as the place where the Franciscan martyrs were buried. In the 16th century the place was marked by the column topped by a crucifix, while in 1543 Bishop of Vilnius Pawel Halshansky built the Chapel of the Holy Cross over it. More than fifty years on, in 1598, a new house for the preacher of the city’s cathedral was built there. Between 1616 and 1630 a hospital for emeritus priests was erected. In 1635 Bishop Abraham Woyna settled the Fatebenefratelli brothers in the vicinity of the chapel.

By the time Franciscans decided to find the remains of their ancestors, a number of new buildings had been erected on and around the site, changing it considerably. Moreover, the land was now owned by the Hospitallers who did not share the interest in Franciscan relics.

In the spring of 1651 the Fatebenefratelli brothers must have been greatly surprised when they saw Franciscans shovelling in their cemetery. Fatebenefratelli brothers immediately voiced a protest, forcing the Franciscans to quit their search. The representatives of the two orders signed a reconciliation accord on 20 June 1650 that concluded the earliest archaeological excavation in Vilnius on friendly terms.

Darius Baronas