Miserable Childhood on Orphan Street

It was the morning of Thursday, 22 July 1781. Walking down a street in Lukiškės, the then suburban area densely populated by Tatars, a passer-by caught a faint sound of a child’s cry and among ripe wheat found lying a baby boy, left there that night or at dawn. To ensure the boy does not die unbaptised, he was brought to St Johns Church on that same day. Andrzej Strecki, a Jesuit father and royal astronomer baptised the boy as Jacob and a nobleman Mateusz Łozowski and his wife Marianna became his godparents.

It is just about all we know about the little Jacob, one of hundreds of foundlings left by their despairing mothers at the gates of monasteries or hospitals, citizen’s doors, or in the streets, forests, and fields. Most babies died and a priest inscribed across in church metrical books.

Foundlings at the care of clerics

Compared to other European capitals, 18th-century Vilnius was a modestly sized city, therefore the number of foundlings was much lower. After the great plague (1709–1710), as the city was slowly recovering, only several foundlings were baptised a year. However, the second half of the century saw a considerable rise in numbers, up to a dozen or several dozen in certain years. This became a significant headache to the local residents and clergy in particular. This situation urged Vilnans to think of appropriate institutional care.

“

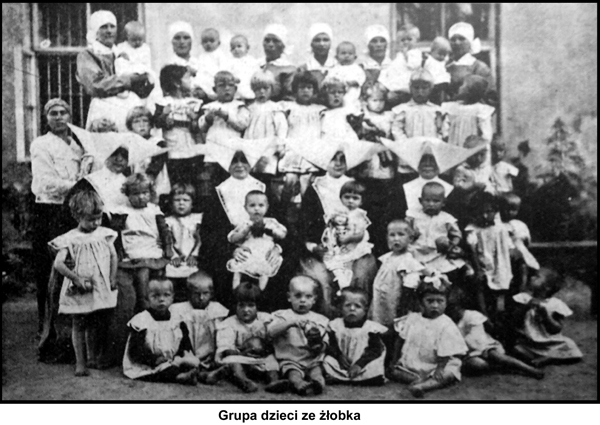

Institutions of infant care formed communities of up to several dozen wet nurses. They were hired local women, living in the city or its suburbs.

On the other hand, repeated appeals to the mothers of illegitimate children were made. Gazety Wileńskie (Vilnius’ Newspaper) wrote on the 2nd of March, 1771: “Head of the new charitable foundation, currently being established, warns the sinnining mothers and recommends that they have mercy on their fruit. Because almost half of the twenty four foundlings taken into the new refuge were injured.”

Ensuring the stable supply of milk was among the primary tasks in saving the foundlings’ lives. Therefore, institutions of infant care formed communities of up to several dozen wet nurses. They were hired local women, living in the city or its suburbs.

In a letter dated 30 July, 1771, the Bishop of Vilnius Ignacy Jakub Massalski wrote to the Dean of St Johns Church Adam Ancypa: “Out of our pastoral sensibility we have established in Vilnius a new foundation for foundlings and children who otherwise have no means of survival. With this goal in mind, we ask you, a man of great grace, for help and oblige you to select wet nurses within your parish who can nurse children, are healthy, of strong faith, and full of love to those around them. […] each wet nurse will be paid, through your person, eight złotys each month for nursing and looking after the children entrusted to them.”

Lady Ogińska’s initiative

“

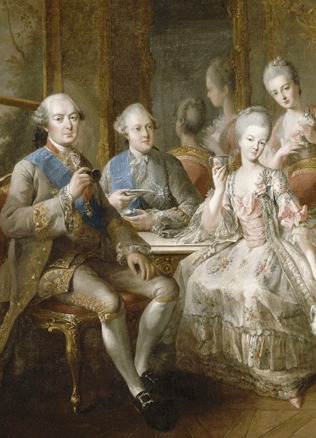

Neither in the 18th century nor before did the state take care of abandoned kids dying in the streets and of people living in utter poverty. Charitable institutions developed only due to the efforts of the elite and local communities.

However, the usual methods did not suffice, because the growing city was reporting ever larger numbers of foundlings. Neither in the 18th century nor before did the state take care of abandoned kids dying in the streets and of people living in utter poverty. Charitable institutions developed only due to the efforts of the elite and local communities. The rich and the mighty acted driven by their personal interest, such as feeling good Christians, fulfilling their Biblical obligation of love thy neighbor, ensuring a faster redemption, building their prestige in the eyes of the others and showing their financial strength.

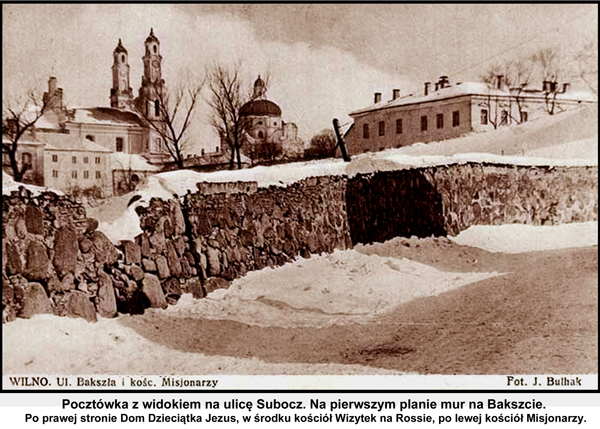

On the 16 December, 1786, the Supreme Tribunal of Lithuania welcomed Jadwiga Teresa Ogińska who expressed her will in the following words: “I, Ogińska, the wife of the Voivode of Trakai, who by God’s grace already lived for quite long in this world, was never able to look at with dry eyes, nor a calm heart, the fact that in Vilnius, the capital of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, among many well-established foundations, none care, shelter, or sustain the orphans who roam the streets and starve, nor the infants abandoned by their parents.” In an attempt to fix the injustice, the wife of the Voivode donated a plot of land and an empty brick building just outside off the Subačius Gate to what was to become the Infant Jesus Hospital.

In five years a two-storey building with a spacious courtyard surrounded and a tall brick wall arose just beside the Church of Ascension and the house of the Lazarites. Over the next five years, a number of other benevolent people, including king Stanisław August Poniatowski, joined the ranks of the hospital’s generous supporters. The Sisters of Charity of Saint Vincent de Paul eventually assumed responsibility for the hospital. They had been nursing the sick at another hospital in Vilnius for almost fifty years and had taken care of hundreds of children.

On Monday, 17th of October, 1791, the new hospital opened its doors. Although over twenty hospitals functioned in Vilnius prior to that, this event sent ripples all over Vilnius and as far as Warsaw. Two weeks later, on the 5 November “Gazeta Narodowa i Obca” (National and Foreign Newspaper) ran a tiny article: “Lady Jadwiga Teresa Ogińska, the wife of the Voivode of Trakai, the lady of great virtues and merits, who had established the Infant Jesus Hospital by [her own] huge funds, now arranged a public relocation of children from the old hospital to the new one […].”

The refuge provided shelter to more than 100 boys and girls. On 29 November 1791, priest Adalbert Czerechowski baptised the first baby boy found at the hospital gate by the name of Tom.

Hope amidst death and stench

The news about the new institution quickly spread fast and soon most foundlings of Vilnius were left at the gates of Infant Jesus Hospital. The hospital saw a great deal more foundlings baptised over its first decade than several parishes of the city combined throughout the 18th century.

Do You Know?

Even though the hospital saved the lives of thousands of children, mortality rates there were punishingly high due to unsatisfactory hygiene and poor health of its inhabitants, many of whom lacked natural immunity. About a third of boys and girls died every year over the first half of the 19th century, the only consolation being the fact that in this respect the Infant Jesus Hospital was on par with many other orphan homes all around Europe.

The Hospital Commission for the Voivodeship of Vilnius discussed the state of affairs in the Infant Jesus Hospital on 16 June 1795. “While visiting the hospitals, the commission […] often finds many sick children; the hospital maintains acceptable level of order and takes tender care of children, yet despite all the efforts seven kids died in five weeks, the main reason for the poor health and repeated deaths apparently being dung, waste and other stinky refuse brought from the town and dumped below the hospital windows […], stench of rotting rubbish and muck then reaches the chambers, where wet nurses and children stay.”

The commission decided that the territory be surrounded by newly planted osiers.

Once grown up, the foundlings could hardly dream of a decent life (many doors were shut to illegitimate children within the society, for instance, they were not allowed to become full members of artisan guilds). Despite that, the nuns and priests tried to ensure that boys and girls under their supervision gained at least basic skills and knowledge. The hospital’s school employed Lazarite priests to teach reading, writing, and the basics of the Christian faith. The boys could learn several crafts, while the girls became accustomed to sewing and washing. This, the teachers hoped, might help their pupils to avoid wrong paths in the future. Unfortunately, their actual lives after leaving the hospital remain an almost complete mystery.

The political order, the city, and the very conception of an institution changed, but the Infant Jesus Hospital remained, at first as a correctional facility and later as an infant house. It became so entrenched in the city that by the late 19th century the nearby street was called the Orphan street. Only in 1966, one hundred and seventy five years after the opening of the hospital funded by Lady Ogińska, the Vilnius Infant Home moved to the newly built premises in Antakalnis, while the old foundling refuge was turned into the Missionary Hospital.