The Building of the Green Bridge: the Doings of the Italian Baroque Mafia in Vilnius

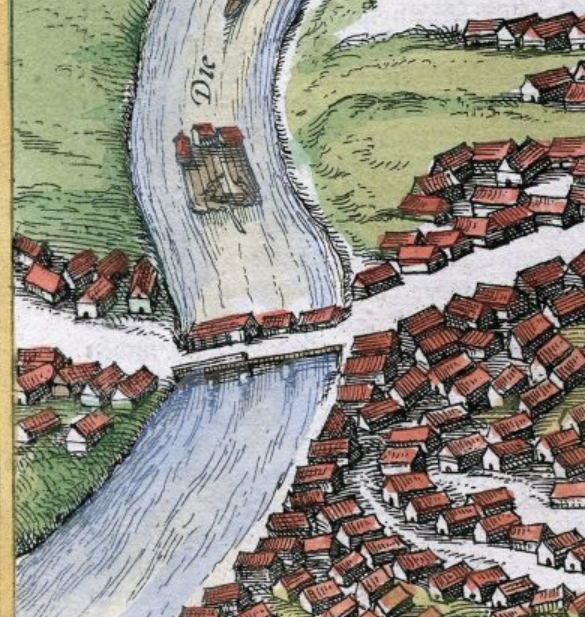

When the wooden bridge over Neris at the present-day Kalvarijų Street collapsed yet again in 1655, Vilnans were forced to use boats and ferries to cross the river for the next fifteen years. In 1670, the Sejm of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth obliged Vilnius magistrate to build a new bridge within two years.

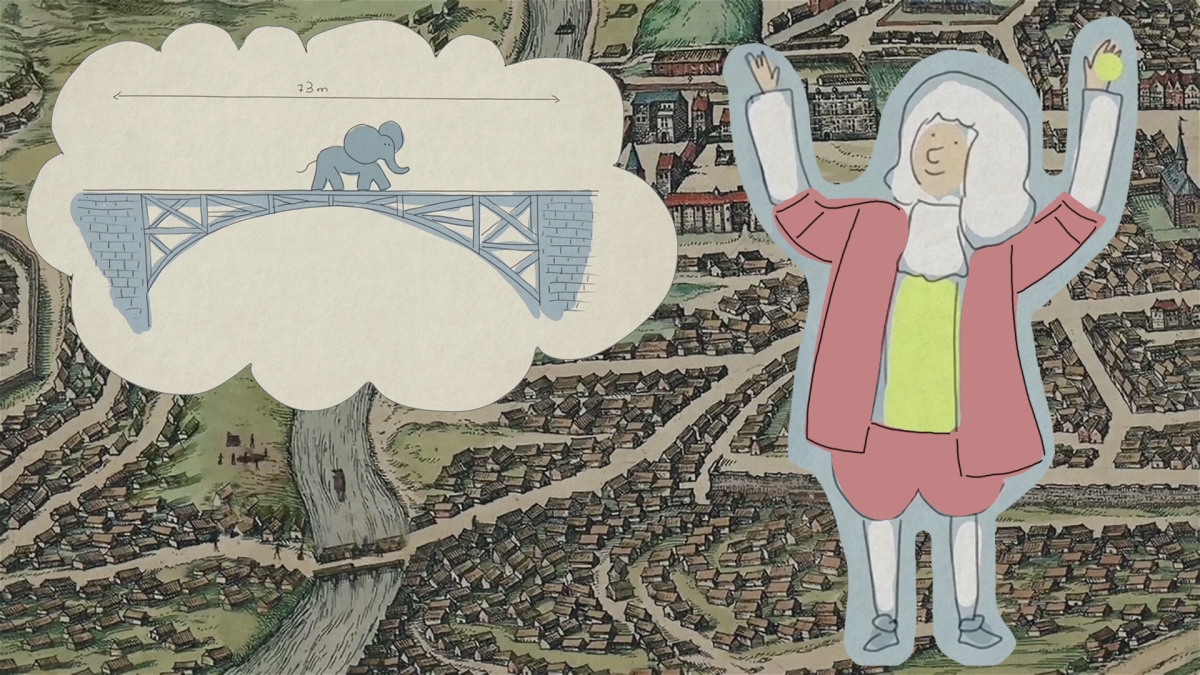

Bartolomeo Cinachi, an Italian served as the wójt of Vilnius (today we would call him the mayor). Soon he introduced the project for a new bridge: it was to be wooden, yet reliable due to the design without intermediate supports, for drifting ice would damage them every spring and necessitated repairs or rebuilding. This plan must have sounded very ambitious, as single-arched bridges were just a theory in 17th-century Europe. The only bridge of this sort was to be built in Pisa, but its construction never began.

Italian “mobsters” in Vilnius

Do You Know?

Bartolomeo Cinachi (d. 1683) was a wealthy financier, born in the city of Lucca. Together with his Warsaw-based brother, he belonged to an influential group of Italian businessmen active in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, the Kingdom of Poland, Royal Prussia, and indeed Italy. The group controlled huge assets and managed the operation of postal service and customs. In Lithuania and Poland, they maintained close ties with the royal court and several magnates, such as the Pac family. Therefore, the group resembled the modern mafia.

However, Italians introduced a number of innovations in Lithuania, by setting up some of the very first private limited companies in the country, popularized the use of promissory notes, developed science and technology.

“

He promised to build a wooden bridge “without precedent in Lithuania or the rest of the world” supported by a 73-metre-wide arch.

Following Cinachi’s directive, the construction of the bridge across Neris was entrusted to wójt’s friend, architect Giovanni Battista Frediani (before 1627–1700), also from Lucca. He promised to build a wooden bridge “without precedent in Lithuania or the rest of the world” supported by a 73-metre-wide arch. All that for a price of 6,000 złotys that was much lower than what the local artisans proposed.

The architect presented a wooden model of the bridge in the spring of 1671. The design has won their “hearts and minds” as even the heaviest man could not break it. The architect promised to build the bridge by the spring of 1672.

The lengthy construction and the result gone down the stream

Once the municipality approved the project, the building works began.

In line with the architect’s plan, the segments of the bridge, consisting of beams joined by bolts, were initially assembled by the river under the supervision of the royal carpenter Martin Fick. Powerful supports on both banks measured at 9.8-metre long, 13-metre wide and 11.7-metre tall were built and only after the completion of the masonry work, it was discovered that they differed considerably and required readjustment.

Then scaffolding had to be built to support the arch of the bridge. It rose too high and part of it had to be disassembled. The magistrate was not happy with the architect who changed the design of the bridge during its construction. All this added delayed the deadlines, yet finally in December 1672 the complete arch rested on temporary pillars.

“

Eventually, once the ice started floating and strong winds blew, the giant edifice, decorated with crosses, collapsed at eight in the evening 10 January, 1673 and slowly drifted downstream. Huge stone supports were all that was left of the bridge, while the floating remains and pieces of the bridge damaged piers and sank a number of ships in the river port at the present-day parliament.

In the first days of the New Year, the magistrate ordered the start of the last stage: the dismantlement of the scaffolding. But the carpenters refused to work without the permission of the architect, who was reluctant to take risk because the thaw started on 6 January 1673. It turned out that Frediani’s cautiousness was well grounded. When he finally ordered to dismantle the scaffolding, the bridge immediately began to rumble and fall. The carpenters fled in terror.

Eventually, once the ice started floating and strong winds blew, the giant edifice, decorated with crosses, collapsed at eight in the evening 10 January, 1673 and slowly drifted downstream. Huge stone supports were all that was left of the bridge, while the floating remains and pieces of the bridge damaged piers and sank a number of ships in the river port at the present-day parliament.

The next day the magistrate assessor together with several servants and a bailiff went almost 100 kilometres downstream up to Kaunas, yet they were unable to find any trace of the bridge. Vilnans finally realised that the bridge was but an affair pulled by the Italians that the city had to pay dearly for. A student of the Vilnius academy Stanisław Samuel Szemet wrote a satirical poem about the bridge and its construction.

International promotion campaign

“

The bridge, the letter went, cost 30,000 złotys to build while around 50,000 złotys was spent on each prior bridge. This was a blatant lie, as the city paid more than 20,000 zlotys for the bridge, thrice its initial budget.

Just one month prior to the disaster, the innovative bridge enjoyed some promotion abroad. A friend of Bartolomeo Cinachi’s wrote a letter to Ismaël Boulliau (1605–1694), the French astronomer and royal secretary dated 7 December 1672 where he describes the bridge with enthusiasm. He wrote of a bridge over a river 400-feet wide, that would demolish earlier bridges every spring, because those were built on pillars resting in the river stream. He said that the new bridge was decorated with stone slabs, its upper part hidden under a wooden cover.

The bridge, the letter went, cost 30,000 złotys to build while around 50,000 złotys was spent on each prior bridge. This was a blatant lie, as the city paid more than 20,000 zlotys for the bridge, thrice its initial budget.

Moreover, the letter claimed that the bridge would have fared better built in another city, where the residents would have appreciated the “talent of the inventor.”

A little later the model of the bridge was apparently taken to Gdansk, thanks to the abovementioned Ismaël Boulliau, and remained there for several years. Its fate is unknown.

The architect accuses the municipality

“

His plan of erecting the single-arch bridge spanning 73 metres may be seen either as a bold attempt to implement the cutting-edge scientific and technical ideas, a reckless experiment, or as a successful plot to swindle some naïve people.

Giovanni Battista Frediani, the architect of the hapless bridge, defended himself claiming that Vilnius magistracy did not supply building materials, nor remunerated the craftsmen, these being the main reasons behind the delay. The judicial process against him supposedly tarnishes his professional reputation.

His plan of erecting the single-arch bridge spanning 73 metres may be seen either as a bold attempt to implement the cutting-edge scientific and technical ideas, a reckless experiment, or as a successful plot to swindle some naïve people.

Not a single bridge of that type was previously built anywhere in the world. It is highly likely that the peculiarities of the construction rendered the design impossible to implement. It only at the end of the 18th century that the single-arched wooden bridges finally exceeded the limit of sixty metres.

The long history of the Green Bridge

“

A bridge built in 1684 survived until 1700, when the stream of a swollen river tore it down. The story repeated itself in 1761 when Neris wrecked the main frame of the bridge. This time the city’s authorities rebuilt it and painted green. It has maintained its Green Bridge name ever since.

Back in the 1529 King Sigismund the Old granted the privilege to the Voivode of Vilnius Albertas Goštautas to build a stone bridge there. It could house merchant shops over it that could be taxed in exchange for the maintenance of the bridge. The construction, however, took much longer than expected, mainly due to faulty masonry work performed by an Italian master. As a consequence, the bridge collapsed three times before its eventual completion.

The year 1536 saw another royal privilege issued, this time to Johann Hosius, the son of the castellan of the Vilnius Castle. Johann was given the right to build “the grand stone bridge” across Neris and collect fees from anyone crossing it. The bridge was apparently erected, most likely it was made of brick and stone, but exact data is lacking. The chronicle written by Alessandro Guagnini in 1578 describes the bridge as “stone-made at both ends, huge, covered with shingles, costing a lot of money”. It was annihilated by the fire on 1 July 1610.

In 1631 yet another bridge was completed only to be destroyed in 1655 by the Lithuanian troops fleeing Muscovite assault. It was rebuilt in 1673 but soon collapsed once more. A bridge built in 1684 survived until 1700, when the stream of a swollen river tore it down. The story repeated itself in 1761 when Neris wrecked the main frame of the bridge. This time the city’s authorities rebuilt it and painted green. It has maintained its Green Bridge name ever since.

Aivas Ragauskas