Gryphon’s Silver Leash, or The Royal Dogs in Vilnius

In the 16th-century Vilnius, the Palace of the Grand Dukes of Lithuania echoed with a multitude of sounds that included the barking, whining and growling of dogs. The Grand Dukes of Lithuania and their family members owned canines of various breeds, ranging from small puppies to exceptional hunting dogs. They travelled together as friendly companions or fashionable accessories. They ran around the palace and the Throne Hall and were even admitted to areas accessible to very few mortals – royal bedrooms. Judging by the 17th-century works of occasional literature, some dogs were even allowed into their owners’ beds.

Do not turn the palace into kennels

All the last Jagiellon rulers, from Alexander (1461–1506) to Sigismund Augustus (1520–1572), owned domestic dogs. Stephen Báthory (1533–1586) and the first ruler from the House of Vasa, Sigismund III (1566–1632), as well as the Queens Bona Sforza (1494–1557) and Barbara Radziwiłł (c. 1522 / 1523–1551), also kept dogs, sometimes brought to Vilnius from far away.

Sigismund the Old had several English dogs (he bought three of them in Buda in 1502) and was especially fond of poodles. On his trip to Hungary, a white poodle named Bielik (Whitey) accompanied the king. It was so usual to see the dog in the presence of the King that he even features in Jan Matejko’s painting “The Raising of the Sigismund Bell at the Cathedral Tower in 1521 in Kraków.”

“

For all his love of dogs, Sigismund the Old did not turn his palace into the kennels, as was the case in the courts of Buda and London in the 16th century. In 1523 he even warned his nephew, King Ludwig of Hungary: “Do not keep dogs in the rooms nor allow them at the table.”

An attendant courtier bathed Bielik once a week from 1500 to 1504, while the master of the royal baths named Sidor, supplied the dog (and the court jester) with soap. For all his love of dogs, Sigismund the Old did not turn his palace into the kennels, as was the case in the courts of Buda and London in the 16th century. In 1523 he even warned his nephew, King Ludwig of Hungary: “Do not keep dogs in the rooms nor allow them at the table.”

Dogs were among the most valuable gifts circulating among the royalty of Europe. The Duke of Mantua Federico II Gonzaga gifted an “exquisite dam” to Queen Bona Sforza in Vilnius, 1534. The gift brought her great joy, she wrote, and she asked to send her more adding that it would delight herself and her son Sigismund Augustus. Most likely on that occasion Gonzaga sent Bichon Maltese pup, because he was particularly fond of the breed. In 1529 Titian painted a portrait of the Duke with a Bichon Maltese by his side.

In his childhood, Sigismund III Vasa had a tiny Papillon, immortalised in Johan Baptista van Uther’s portrait of the two-year-old Prince and his puppy (1568). Much later, on arrival in Vilnius, he would bring along several Spaniels for hunting. Peter Paul Rubens painted the equestrian portrait of the King accompanied by a brown-and-white Spaniel.

From a fur jacket to an angry kick

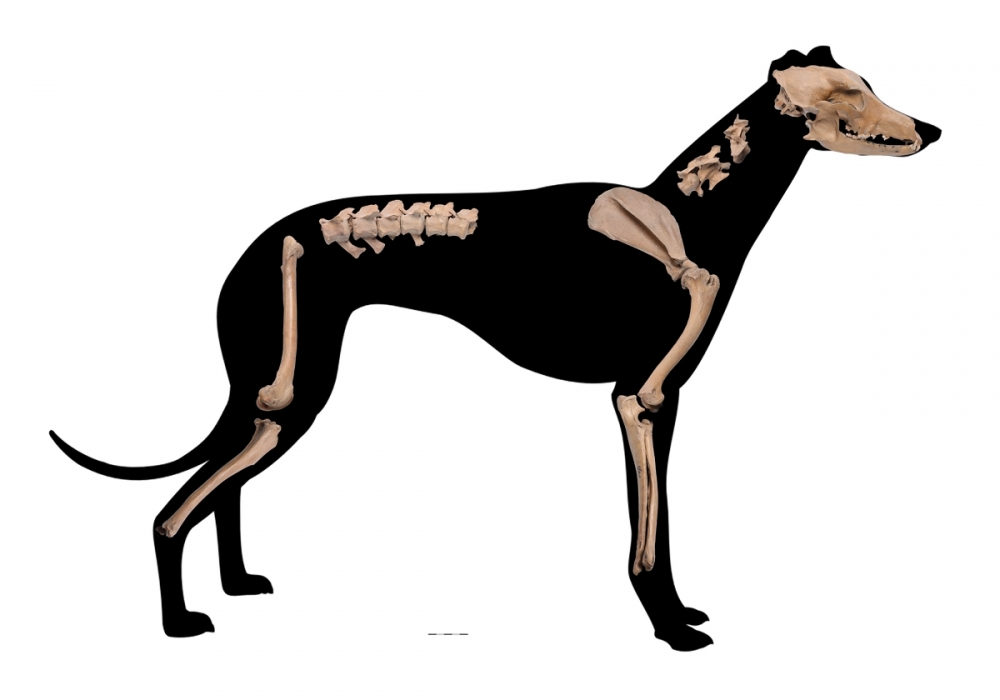

Seven cherished hunting dogs ran around the palace of Sigismund Augustus and Barbara Radziwiłł. Their favorites were a Greyhound bitch Sibyl and a Molossus dog Gryphon.

Do You Know?

A special servant attended and fed them from copper bowls. The dogs were bathed and groomed, their hide cut,and their apparel and accessories taken care of. Sibyl and her puppies wore fur jackets and had fox tail blankets to protect them from cold in winter.

“

Four hunting dogs, most probably Greyhounds, called Shmiga, Obruchitsa, Horwath, and Shukay, ran inside king Stephen Báthory’s chambers. A passionate hunter and canine expert, Stephen Báthory gave the following reasoning behind the death sentence to a Polish magnate in 1584: “Canis mortuus non mordet” (A dead dog does not bite).

The royal canines wore deluxe leashes made of black velvet or silk with collars bearing imprints of gilded silver. Gryphon had a silvered collar, just like the royal dogs in other European courts. They were well taken care of and partookin specialty products, such as honey, radish, oil, and hare fat.

Four hunting dogs, most probably Greyhounds, called Shmiga, Obruchitsa, Horwath, and Shukay, ran inside king Stephen Báthory’s chambers. A passionate hunter and canine expert, Stephen Báthory gave the following reasoning behind the death sentence to a Polish magnate in 1584: “Canis mortuus non mordet” (A dead dog does not bite).

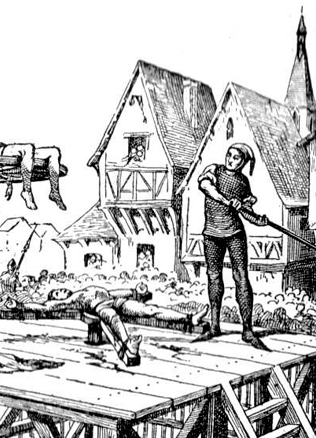

One of the King’s dogs caused some inconvenience to Dominic Ridolfino, an Italian military engineer who arrived in Vilnius in 1580. He happened to step on a Greyhound’s paw while leaning forward to kiss the King’s hand and had his calf bitten. Seeing this Stephen Báthory turned furious and kicked the Greyhound with such velocity that the poor dog flew right to the centre of the hall.

The prized job of the royal dog keeper

Do You Know?

The largest packs of dogs, of up to two hundred Hounds and Greyhounds, were kept well outside the Palace of the Grand Dukes, in the royal kennels. The first ones were located well outside the city, in what is today Valakampiai, beside the then summer residence of the ruler. By 1553 they were moved closer and occupied the area between the present-day Green and Mindaugas Bridges. At the time the royal kennels shared the space on the right side of River Neris with fishermen’s houses, a brickyard and a glass workshop. The kennels employed dozens of servants of different ranks, all taking care of the dogs. Some dog keepers were meant to train them, others took them hunting, or fed them.

Šunidėse gyvūnais rūpinosi specialūs dvaro tarnai – kelių rangų šunininkai: vieni dresuodavo, kiti vesdavo į medžiokles, dar kiti ruošdavo ėdalą.

Alexander Jagiellon employed eighteen dog keepers of Lithuanian and Ruthenian descent. Sigismund Augustus’ staff of dog attendants included several foreigners, mostly Italians and Germans. In addition to their duties, they were expected to accompany the dogs sent to other courts as presents.

“

Some of them enjoyed a very special menu, the example being the Hounds that Sigismund Augustus received as a present from emperor Maximilian II in 1569. They were fed exclusively on bread and butter. The King’s other hunting dogs indulged in wether meat, pork ham, lungs, and poultry. The peasants of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania could only dream of such a well-balanced diet.

Some dogs received special training to prepare them for bear hunting or bear sicking within enclosed arenas. Renaissance author Łukasz Górnicki refers to this type of entertainment in an anecdote mocking the widespread bribery. During a bear sicking spectacle in Vilnius, Sigismund Augustus spoke of the dogs being overfed as the reason for their unwillingness “to take” the bear. In reply to this, one of the noblemen present, Dymitr Chaletski, said: “Just let your scribes in, Majesty. They’re eager to take no matter what.”

In no way the royal hunting dogs could have complained about the care and food they received. Their rations included more than enough fat, oats, and bread. The oats, cleaned and dried, would be further baked in the oven until brown, and then ground into coarse flour. Whenever dog attendants wanted their canines to gain weight, they would add up to a sixth of ground rye into the flour. This would then be mixed with fat and different parts of meat seasoned with blood, fried pieces of pork fat and a bit of salt. The mash would then be braised, cooled off and fed to the dogs.

Some of them enjoyed a very special menu, the example being the Hounds that Sigismund Augustus received as a present from emperor Maximilian II in 1569. They were fed exclusively on bread and butter. The King’s other hunting dogs indulged in wether meat, pork ham, lungs, and poultry. The peasants of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania could only dream of such a well-balanced diet.

Raimonda Ragauskienė