Public Examination in Vilnius: a Form of School Promotion

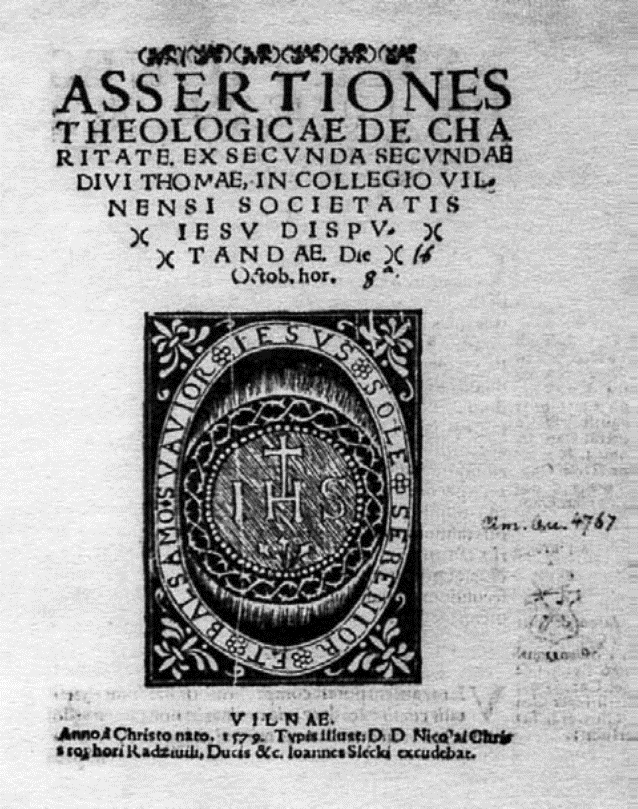

The tradition of public examination at Vilnius University is centuries old. Since its establishment, the university intended to be open to the public. The papal bull issued by Gregory XIII in 1579 instructed that bachelor’s degrees in arts, philosophy and theology, licentiate, master’s, and doctoral degrees should be awarded only after an examination followed by a public debate attended by at least five professors. The Jesuit teaching model, Ratio Studiorum (1599), also provided for public examinations.

From China to Prussia

“

In many European universities, students have long taken oral examinations. They had to answer questions, discuss, defend their thesi and even give public lectures.

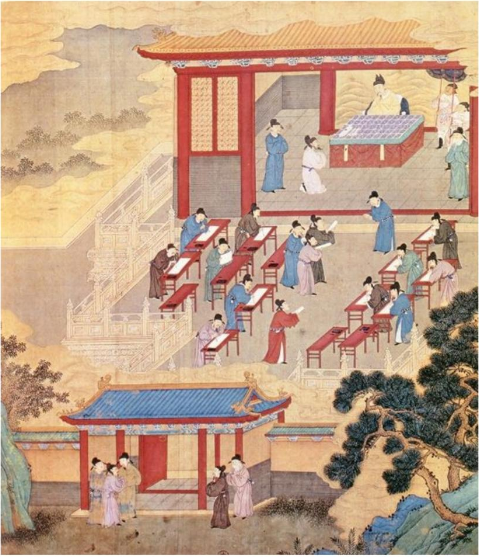

The tradition of written exams has developed in East Asia. The future civil servants of Imperial China had to undergo a public examination in as early as the 2nd century BC. Candidates were required to answer questions by submitting an essay consisting of eight parts.

In many European universities, students have long taken oral examinations. They had to answer questions, discuss, defend their thesi and even give public lectures. Since the 18th century, as the number of students was rapidly increasing, Prussia, France and other countries introduced written exams. For some disciplines (such as mathematics) this method was much more reliable.

Grading was introduced in the late 18th century Cambridge.

Priesthood for the lazy

“

Students had to take exams from the first year, either to move to a higher level or change the subject. For example, if a student who had begun his studies in philosophy did not reach the intermediate level, he was not qualified to undertake scholastic studies and had to limit himself to moral theology, the bare minimum required for becoming an ordinary priesthood.

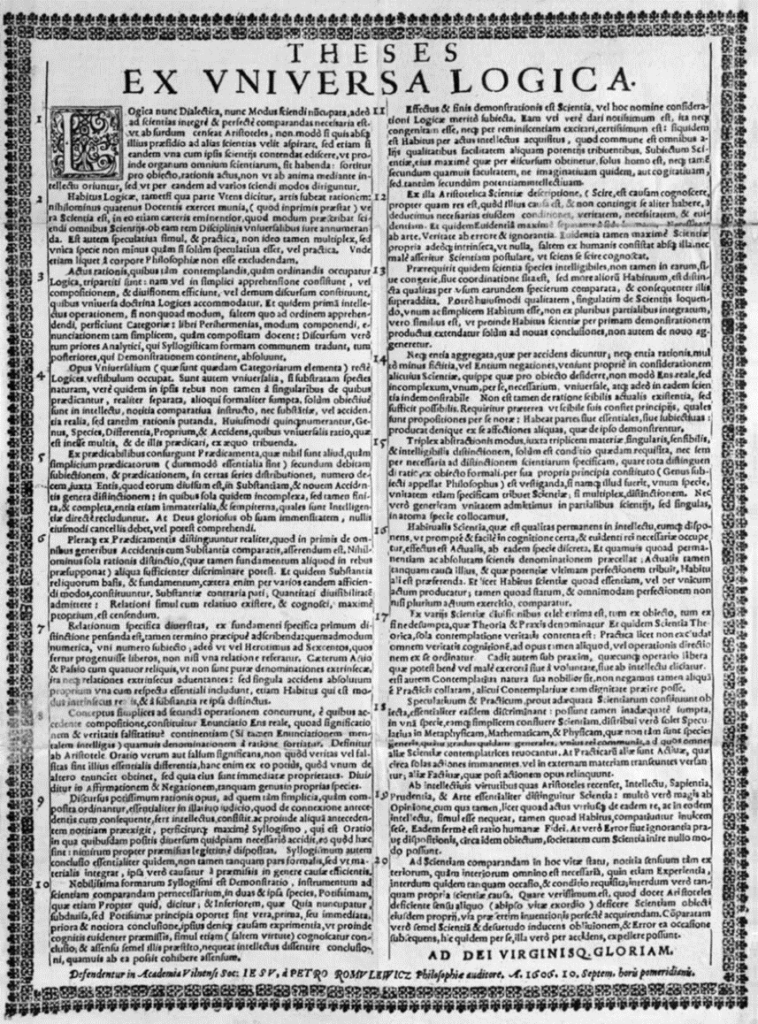

Only a few fragments of exam material at Vilnius University have reached our days. The surviving Book of Vilnius Provincial (1585-1642) and The Examinations in Theology and Philosophy at the Vilnius Jesuit Academy (1688-1773) offer some hints as to what the examination model looked like.

Students had to take exams from the first year, either to move to a higher level or change the subject. For example, if a student who had begun his studies in philosophy did not reach the intermediate level, he was not qualified to undertake scholastic studies and had to limit himself to moral theology, the bare minimum required for becoming an ordinary priesthood.

Students were also examined once they were ready to graduate to the next year of their studies. This exam was closed to the public and took place in February, in the middle of the academic year, and the student’s mentor had to be present.

Applying for an academic degree often involved taking part in a public philosophical or theological dispute. The modern procedure of defending a doctoral thesis was not practiced back then.

Thousands of “degreed” students

“

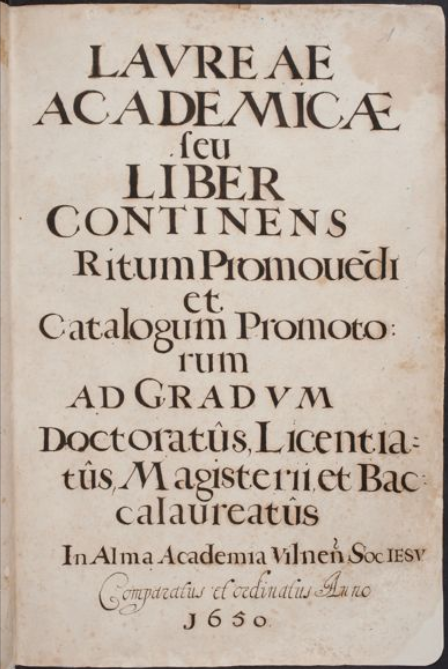

The hand-written register of “Academy laureates” lists more than 4,000 people who graduated from Vilnius University between 1583 and 1781 with a degree in philosophy, theology, civil and canon law. This includes nearly 2,500 graduates in liberal arts and philosophy, another 400 in theology, while the remaining 1100 graduated with a degree in law.

Theoretically, any citizen of Vilnius could participate in the public dispute, but only those with the appropriate education had the right to ask questions and express opinions: professors, theologians, masters of liberal arts, and the scholarly Jesuits. The candidate for the degree had to outline his key statements and present conclusions. Then the opponent and other participants were asked to speak. The aim of this exercise was to prove the student’s ability to formulate a problem, present its solutions, and to defend them.

The hand-written register of “Academy laureates” lists more than 4,000 people who graduated from Vilnius University between 1583 and 1781 with a degree in philosophy, theology, civil and canon law. This includes nearly 2,500 graduates in liberal arts and philosophy, another 400 in theology, while the remaining 1100 graduated with a degree in law. Just as today, not everyone managed to graduate and even fewer achieved graduate degrees.

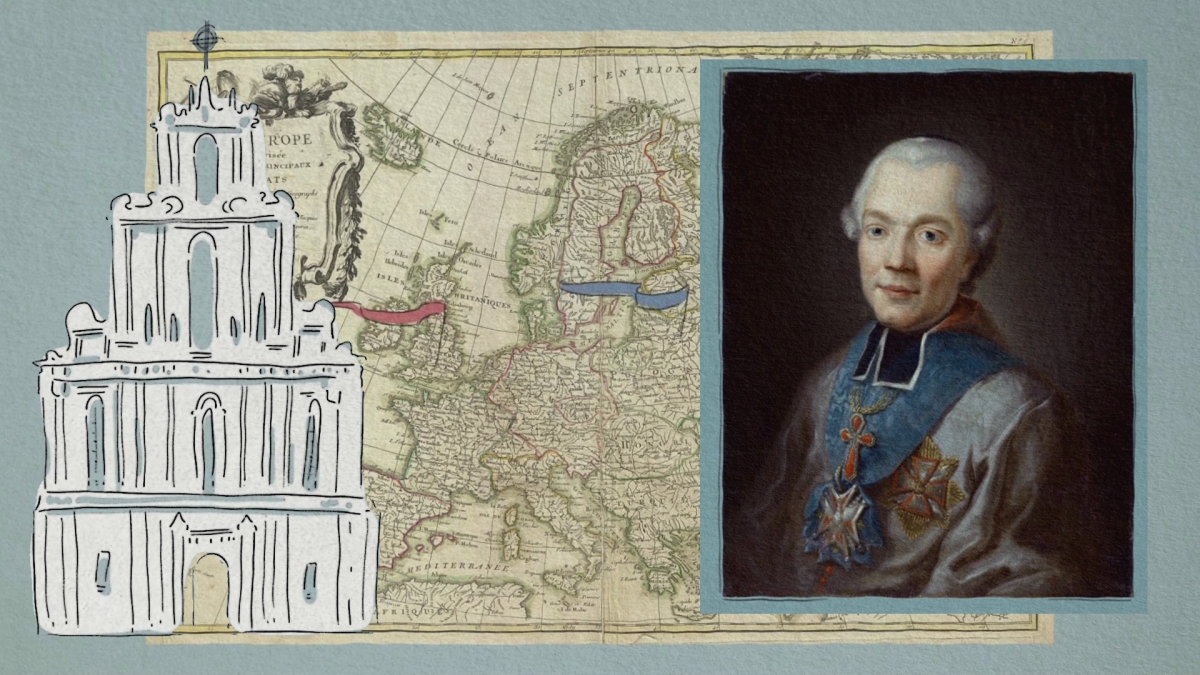

Sometimes a public exam guaranteed a student a career. Bishop Ignacy Massalski noticed Laurynas Gucevičius, then a young architect, during his exam and became his patron.

Your thesis is your own concern

For nearly two centuries, from 1579 to 1762, Vilnius University maintained the tradition of accepting only printed theses when applying for a doctorate in theology, otherwise a manuscript sufficed. Candidates had to take care of publishing their theses. Usually they sought for patrons to help with publishing a small book or a large printed sheet. Students expressed their gratitude by inscribing a dedication to their patrons.

Bachelor’s and licentiate degrees in theology were usually granted without the public defence – an exam sufficed. The same applied for bachelor’s and master’s degrees in philosophy. Only the most talented were invited to public debates, but even this did not always guarantee a high level of discourse. One mid-17th-century eyewitness account reads: “It often happens that undeserving candidates are allowed to defend their theses.”

Do You Know?

The defence of thesis and the award ceremony was held at St Johns’ Church or at the Jesuit residence in Lukiškės. Usually it was solemn and slow, except the only instance in October 1773, when, knowing that the pope was about to abolish the Jesuit Order, university professors awarded doctorates in philosophy, canon law, and theology to nearly 150 individuals in one fell swoop.

Examination made public

With the advent of the Enlightenment in the 18th century, people in charge of universities and other schools wanted to make them more open to the public in order to show their importance and the social benefits they offer. For Vilnius University, then still run by Jesuits, it meant a transition to a new level. Public debates were no longer enough, now the university wished to speak about the content of studies and the strategic and current results. The exams were made public and could be attended by politicians, officials, and other representatives of the elite.

“

The most important public exams were held in July, at the end of the school year. Parents and relatives came to support the students, while the university invited dozens of honourable guests – church and secular figures.

The most important public exams were held in July, at the end of the school year. Parents and relatives came to support the students, while the university invited dozens of honourable guests – church and secular figures.

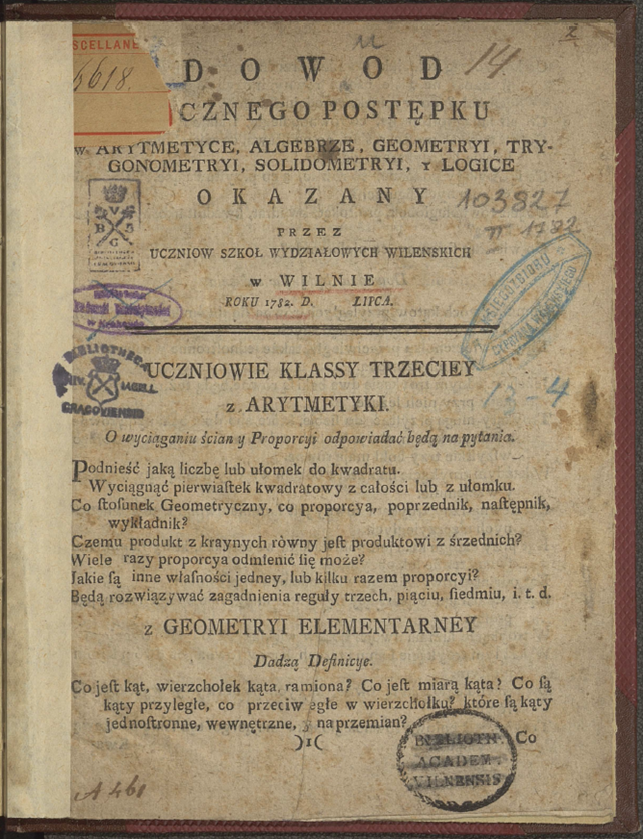

Since the 1760s, the university began publishing occasional books (about 100 copies each) titled The Evidence of Progress, The Annual Report, etc. They included study and exam programs as well as an outline of achievements. Those were published by high-ranking academic institutions, such as the College of Nobles and the College of Piarists.

Uniate and Calvinist schools also issued their study plans, aiming to maintain a positive image and attract new pupils.

The Jesuit rivals

The Piarist College established in 1726 became a strong rival to Vilnius University, as it was an innovative institution of learning. It was closed down in 1741 after a long period of clashes, but opened up again in 1750, when the Piarists were granted the privilege to establish a boarding school. It was very exclusive as only 24 pupils were present, but held in very high regard as the nobility’s elite trusted the Piarists with their scions. The education was focused on the hard sciences, economy, law, and foreign languages.

The Jesuits dominated the field of higher education and preferred a more arts-centered approach. The society benefited from the Jesuit and Piarist rivalry, as it fuelled the improvement of education.

At times the rivalry took unexpected forms. In December 1759 Duke of Courland and Semigallia Charles of Saxony was visiting Vilnius and accepted the Piarist invitation to participate in the exams of their boarding school. However, the Jesuits overtook the duke and convinced him to visit the university, where the students delivered public speeches in French and Polish. However, the esteemed guest managed to visit the Piarist students too.

“

At times the rivalry took unexpected forms. In December 1759 Duke of Courland and Semigallia Charles of Saxony was visiting Vilnius and accepted the Piarist invitation to participate in the exams of their boarding school. However, the Jesuits overtook the duke and convinced him to visit the university, where the students delivered public speeches in French and Polish. However, the esteemed guest managed to visit the Piarist students too.

Rivalry forced the Jesuits to establish the College of Nobles, a boarding school aimed at the offspring of the nobility’s elite, bearing many similarities with the Piarist college. It became a separate institution in 1751. The elite school did not award academic degrees and focused on publicizing the exams. Pupils showed their excellence in many fields, ranging from rhetoric to philosophy, architecture, and mechanics.

The Vilnan College of Nobles was the only Jesuit institution of its sort in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. Its pupils were instructed in mathematics, German, history and geography, as well as French. French bore an exceptional status in the school, as it was the language of instruction in certain disciplines and it was taught by the exiled French Jesuits. Law, mathematics, mechanics and other public exams pupils were supposed to communicate with their teachers and the public in Polish and French, while at the conclusion of the exam they were to express their gratitude in French. Pupils acted in French comedies, analysed Polish prose in French and vice versa, cited French thinkers in their original language, and translated their works into Polish.

Lastly, the pupils were instructed in fencing, horse riding, dancing, and painting.

By Aivas Ragauskas